Following John Bozeman's Footprints

In the spring of 1860, John Marion Bozeman left behind a wife and three daughters in the mountains of northwestern Georgia to seek his fortune mining gold in Colorado. Evidentially, gold fever ran in the family. His father had left him, four other children and a wife for the gold rush in California when John was fourteen. Arriving in Colorado, however, John soon discovered that the best claims were already taken.

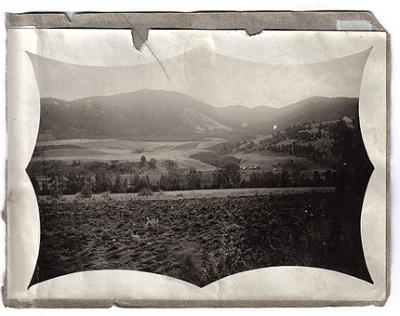

Always a trail blazer, he acted upon rumors of better fortune in Montana and traveled to Deer Lodge Valley with fifteen other men from the Colorado group. Disappointing returns greeted him there as well, so six months later he moved to Grasshopper Creek in the Beaverhead Valley. Eventually, Bozeman’s dreams of discovering gold fizzled. Mining was drudgery, he discovered, and he was not at all suited to that kind of arduous labor. Recognizing a better opportunity for wealth and adventure, he soon began to blaze a new trail into Montana and Idaho.

In the early 1860’s new mining claims in Montana and Idaho continued to attract a steady stream of fortune seekers. Some came up the Missouri River to Fort Benton then traveled south to the mines. This route was slow and expensive. Others traveled over the Oregon Trail to Fort Hall in Idaho then north. This second route was longer with mostly barren land. Fortunately, Bozeman perceived the need for a shorter, safer route.

Bozeman and a well-known mountain man and guide, John M. Jacobs, left to find just such a route. Sharing an adventurous spirit, they traveled to Three Forks, crossed the Gallatin Valley over what is now the Bozeman Pass enroute to the Midwest. Known to Indians, explorers and trappers, the route had served as a travel corridor since prehistoric times.

Delayed by serious Indian encounters, they eventually arrived at the North Platte River. Apparently, Bozeman continued to Council Bluffs, Iowa in search of immigrants to join his wagon train. He then returned to rendezvous with Jacobs along the Oregon Trail near Glenrock, Wyoming.

From its beginning at Fort Laramie on the North Platte River, the Bozeman Trail ran northwest across the headwaters of the Powder and Tongue Rivers east of the Big Horn Mountains. North of the Big Horn and Pryor Mountains it cut across Clark's Fork and other streams from the Beartooth Mountains until reaching the Yellowstone River east of present day Livingston. It arrived in the Gallatin Valley by way of the Bozeman Pass where it merged with other trails going to Virginia City.

When Bozeman and Jacobs set out with their wagon train, the trail was not yet marked for wagons, so the threats from Indian attacks were great. However, the cutoff promised to be shorter than the trip to Bannack via the Oregon Trail Idaho route by nearly 400 miles. Many among the group had heard of the Grasshopper Creek gold strikes and were eager to be on their way.

Soon, though, warnings from Sioux and Cheyenne representatives frightened the members of the train, causing most to turn around. Jacobs accompanied those people back to the North Platte River where they went on to take the Oregon Trail to Fort Hall. However, John Bozeman plus ten strong men braved the trail on horseback. The ten arrived in August 1863 at Alder Gulch.

One man, George W. Irvin II, praised Bozeman’s leadership, “There was one who knew no such word as fail. It was John Bozeman. He succeeded in imparting to us some of his restless energy and inspired us with his indomitable courage.” George Irvin later became a prominent Butte citizen and suggested the pass into the Gallatin Valley be named Bozeman Pass.

Bozeman, who was not discouraged by the failure of his original expedition, soon joined a small wagon train leaving Virginia City to head back to the Midwest. This time he traveled all the way to Missouri to gather another group of pioneers. This successful trip in 1864 is glamorously told in a story about a race between John Bozeman, the young adventurer and Jim Bridger, the famous mountain man. Each man guided rival wagon trains over different routes from Fort Laramie, Wyoming to Virginia City, Montana. Bridger’s route took his train west through Wyoming to the headwaters of the Big Horn River, north through the Wind River Canyon, down between the Big Horn Mountains and the Rockies, arriving in the Gallatin Valley through what is now known as Bridger Canyon. He claimed his route was 100 miles shorter than Bozeman’s, avoiding Indian lands thus making it freer from attack. Bozeman maintained that his route east of the mountains was a natural corridor with plenty of water, grass and wood.

In John M. Bozeman, Montana Trailmaker Merrill Burlingame writes, “Bridger and Bozeman were both working for the Missouri River and Rocky Mountain Wagon Road and Telegraph Company.” The company was looking to profit from fees on ferryboats at several crossings on the Yellowstone River. They enlisted Bozeman and Bridger to make assessments for potential ferry crossings. The “race” was more likely a good-natured challenge for each man to prove the merits of his own trail. It is not certain who arrived first, but all accounts agree a confident Bozeman departed from Fort Laramie a few weeks later than Bridger.

The most plausible account of the finish given by William W. Alderson, a leader in the new Gallatin Valley settlement, recorded that Bridger arrived July 6, 1864. John Jacobs followed shortly thereafter. Jacobs departed from the Bridger route, bore south and came to the Gallatin Valley over the Bozeman Pass. John Bozeman arrived last on August 9.

Bozeman strongly believed that developing towns and the agricultural possibilities of the Gallatin Valley would be of more lasting value than the allure of mining which had brought him West. Before he left on his 1864 expedition, he enlisted William J. Beall and Daniel E. Rouse who were operating a ranch near Three Forks to lay out a townsite near the passes which led to the Yellowstone Valley.

Shortly after the arrival of his wagon train on August 9, Bozeman realized his dream of creating a town. A claim association was formed, by-laws were enacted, recording fees were fixed, and other business necessary for the new community was transacted. “On the motion of W. W. Alderson it was resolved that the town and district be called Bozeman,” state the records.

During his three-year residence in the Gallatin Valley from 1864-1867, John Bozeman left a lifetime legacy. He brought hundreds of immigrants by wagon trains to the area, establishing the town of Bozeman where they might reside. He had interests in farming, real estate, hotels, mills, flat river boats and ferry operations and in the general welfare of the community. Bozeman is the one who influenced Thomas Cover and P. W. McAdow to build a flourmill at the edge of town.

On the morning of April 17, 1867 Bozeman left town for the last time in the company of Thomas Cover. Cover wanted to go to Fort C. F. Smith on the Big Horn River to procure flour orders for his mill. Prompted by reports of Indian problems, he asked Bozeman to accompany him as the trip could also provide an opportunity for Bozeman to survey sites for ferries as he had done previously.

Despite a sense of foreboding, Bozeman agreed to go. On April 18 he died on Mission Creek near the Yellowstone River and present site of Springdale, Montana. He was 32 years old. Accounts of his death varied. The most accepted version said that he was killed by a group of renegade Blackfoot Indians masquerading as Crow. Another version suggested that he was murdered by Cover and a third implicated a jealous husband. The mystery will never be solved.

What is known however is that John Bozeman’s death may have insured the survival of the town he established. Fear of Indian attacks led the government to build Fort Ellis in 1867 just three miles north of Bozeman. It not only provided protection but also offered a ready market for Bozeman businesses and its farming community. John Bozeman left his footprints in the sand all over the Gallatin Valley. From the Bozeman Pass to his namesake restaurant, his presence is both seen and felt.

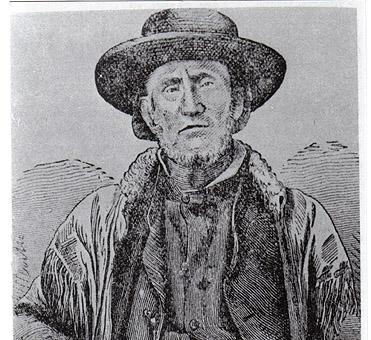

John Bozeman (Photo 1)

John Bozeman was six feet two inches high, weighing 200 pounds, supple, active, tireless, and of handsome, stalwart presence. He was genial, kindly and as innocent as a child in the ways of the world. He had no conception of fear and no matter how sudden a call was made on him day or night, he would come with a rifle in his hand. He never knew what fatigue was and was a good judge of all distances and when you saw his rifle level you knew that you were not to go supperless to bed.

George W. Irvin II, Butte Miner, January 1, 1889

Jim Bridger (Photo 2)

Over the fifty-year span of his Western travels (1822 – 1871) Jim Bridger explored more previously unknown territory than any other white man of his century. He roamed the Rocky Mountains from end to end and side to side and back again; skirted the towering frosty peaks, of the Grand Tetons; and penetrated the grim dark bastion of the BigHorns guarding the matchless hunting grounds of the Sioux. No one was a greater frontiersman.

Norman B. Wiltsey, “Jim Bridger He-Coon of the Mountain Men,” Montana the Magazine of Western History, Winter, 1956 issue

Leave a Comment Here

Leave a Comment Here