A Montana Cattle Drive

On a Thursday morning in the heat of July 2007, I packed my cowboy boots and set out for Madison County’s beautiful Ruby valley. The challenge to live in the West as it was—and still is—drew me to the historic Tate Ranch and Upper Canyon Outfitters (UCO). This extraordinary family operation offers guests a range of outdoor adventures from fly-fishing to seasonal hunting. But it was the cattle drive that beckoned me.

UCO cattle drives are a unique learning experience in a working partnership with local ranchers. To participate in this important, historic activity is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I set out not just to observe the working cowboy’s life, but also to live it.

The 24-mile drive from Alder south follows the sparkling Ruby Reservoir, then opens to ranchland. The Ruby River cuts through the valley like a blue satin sash against green pastures and cultivated fields. [1] Antelope and deer mingle with the livestock even at midday. James Williams, former captain of the famed Vigilance Committee, settled in the valley to raise cattle and C. S. Larabie, W. H. Raymond, and others bred top-notch thoroughbreds and trotters. Historic barns and remnants of their ranches dot the valley.

I admired Ted Turner’s neighboring spread and his grazing buffalo. Around the bend, I caught a glimpse of UCO. [2] Family patriarch, Earnest Peck Tate, arrived in 1912 to join his brother, Addison, foreman of Larabie’s ranch. Peck trained Larabie’s trotters and homesteaded nearby. WWI intervened. Peck sold his cattle, enlisted in the Marines, served in Europe, and returned home to purchase the Upper Canyon Ranch. He and his wife, Mary, raised six children. Their son, Bill, and his wife, Bernice, began setting places for guests in 1981.Today, their son-in-law and daughter, Jake and Donna McDonald, carry on the Tates’ hospitality managing UCO.

I noted Bill Tate’s hay harvest in progress as the McDonald’s modern lodge—home base for the next week—came into view. Donna and Jake warmly welcomed me and introduced the other guest wranglers: Carol Ydens and her daughter, Mareika, from New Mexico; Peggy Wilson and her daughter, Terri Terry, from North Carolina; equine veterinarian, Dr. Amy Grice, and her son, Jacob Leach, from New York; and Pete Lepore of California. Some were veterans of past drives, and we were all eager to begin. After lunch, horses and riders paired up while Donna and her daughter, Cassie, assessed our skills. UCO’s steady horses would carry us far over the next few days.

Early Friday morning, the wind howled through the upper canyon. Despite 90-degree daytime temperatures, nighttime was cold. Wranglers brought in the horses and we helped load the two trailers. The horses knew the routine: they clattered willingly into their places.

An hour later, Carol and Steve Wilcox greeted us heartily. The McDonalds seek partnerships with ranchers like Steve who work closely with state and federal agencies to maintain the land as a sustainable resource. Steve graciously welcomed our non-professional participation. He had vaccinated and branded most of his Red Angus calves during spring roundup, but a few were born late. Rounding up, branding, and vaccinating these latecomers was to be the day’s work.

Shadows cloaked the coulees and draws, hiding the cows and their calves in purple, sunless patches of early morning. The air was still cool and the countryside breathtaking. Temperatures rose as we collected the cows and their calves, then headed back to the Wilcox place. Counting heads showed one tiny, late-born calf missing. A missing calf—worth $200 and $300—means lost income. Despite a search, Steve never found it. Coyotes likely got it first.

Wranglers separated the calves while their mothers bawled and fretted. We learned the process. [3] Steve’s son, Lane, roped each calf’s hindquarters, while another’s waiting hands grabbed the tail, and turned it branding side up. With a volunteer on each end holding its legs, each calf received two vaccinations and then the electric branding iron—a modern convenience—left its smoking mark. [4] One by one the calves cavorted off to find their mothers, a process called “mothering up.”

A few of us tried throwing a calf and holding it down. The calves put up a good fight. [5] The mothers bawled as they watched their babies go though the ordeal; it was pitiful, and a young member of our group fought back tears. One white calf, whose mother was a dairy cow, stood out from the other big-eyed brown ones. We named it “Lucky” because this calf would have a life quite different from that of the beef cattle. After each had its “L lazy S” brand and mothers and calves were reunited, the work was over. We drove the fifty cows and newly-branded calves to nearby pasture.

Carol, a terrific cook, had lunch ready. As we enjoyed the meal, Steve told us about his log barn. Built as a stage stop in the 1860s, its loft hosted many Fourth of July dances. [6] The barn would be swept clean, the animals housed elsewhere, and the holes in the floor covered so that during the partying, no one would end up in a stall below.

That evening back at UCO, we had a bountiful dinner and tumbled into bed. Bawling cows punctuated my dreams. Next morning, Saturday, we headed to the Bradley Ranch where we would work for the next two days. Historically the Belmont Park Ranch, named for the famous trotter Commodore Belmont, the Raymond brothers raised prize thoroughbreds and trotters in the wonderful 1886 log barn. [7] It gave me goose bumps to discover a faint pencil sketch of the prize-winning horse, recalling the days when the Raymond trotters occupied the stalls.

The day’s task was to round up stray cows and return them to the main herd. It was rugged, hilly country with mountains hazy in the distance. Ranch manager, Pat Browne, gave us a warning. “Stay away from the bulls. They will charge your horses,” he explained. “And watch for lethal barbed wire. Homesteaders long ago left the place littered with it.”

We separated into groups to search the draws and coulees. The spectacular Montana landscape surrounded us. Each rider worked according to ability, some doing more and others less. There is never any pressure on these drives. You find your own comfort zone; whatever that is, you go with it.

Three hours later, Pat and his group were scouting high upon a ridge. Kermit, one of the horses, stepped into the deadly barbed wire, slashing a wound above and behind his front hoof. Veterinarian, Amy Grice, happened to be with this group. Kermit—a testament to the excellent, steady UCO horses—did not panic. As blood spurted, he stood still. Everyone scrambled to find something to apply pressure to the wound. One rider produced a super absorbent sanitary napkin and each contributed a bandana. With the pad tied securely over his injury, Kermit began a slow descent. His heroic calm, Amy’s medical expertise, and quick thinking saved Kermit’s life. Pat vowed to make super absorbent pads and bandanas standard equipment. Back at UCO that night, Amy gently doctored Kermit and gathered us all for a thoughtful lesson on the anatomy of a horse’s hoof.

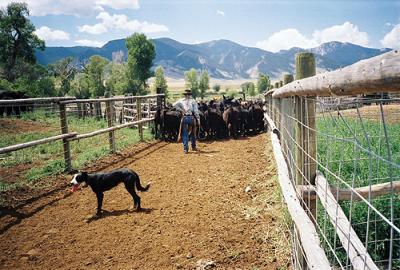

At the Bradley Ranch on Sunday morning, a thousand head of Black Angus speckled the hills. Sixteen of us fanned out around the perimeter of the herd, pushing the cows back to the ranch. [8] It was a thrill trailing behind that black, undulating sea of cattle. With the herd corralled, [9] wranglers sent 15 head at a time into the corral’s alleyways. Armed with long switches, we diverted the bulls, cows, and calves into separate pens. [10] The mothers and calves would remain separated for now. Their deafening cries made me wonder if the Browne family would sleep that night.

The calves—previously branded—had yet to be vaccinated. [11] It was hot, hard work critical to the health of the herd. These calves, older than those at the Wilcox place, were challenging. Each rambunctious one entered a chute that closed to immobilize it for the needle. Finally, we counted the last of 515 calves. [12] Back at UCO, we devoured grilled salmon and received good news: Kermit was improving!

On Monday morning, Pat and his crew loaded the thousand cows and calves, still separated, onto fourteen trucks bound for Three Forks Camp in the Beaverhead-Deer Lodge National Forest above the Tate Ranch. All morning the trucks rumbled past. While we waited, Bill Tate took us up to the small local cemetery where we found “Cap” Williams’ grave, and we visited Kermit who was healing nicely. Then we packed up for two nights’ camping at Three Forks.

At camp, the cows and calves waited in pens, too crowded to mother up. The object was to drive them two miles to pasture where they would reunite and graze until the next morning. But the hot and thirsty cows headed straight for the creek. In a flash they were off course. [13] Getting them out was difficult. Jake’s famous cow cry, “Hy up! Hy up! Git on outa hee-ar!” made us all laugh. We marveled at Pat’s crazy wrangler and the unbelievable places he took his horse to retrieve the strays. It became clear how important the ever-present dogs are to the drive. Jake’s Tim earned his keep, instinctively knowing where the cows should and should not go.

With the herd safely pastured, we looked forward to the big barbecue at camp. Everyone we had met over the last few days and many others came to celebrate. [14] We enjoyed the great food, great music, and lots of laughter, but bedded down early for the final drive.

The cooks woke us at 3:30 AM. After a hearty breakfast, Cassie and Lane brought the horses up from UCO. We rode out in bitter cold. The cows moved well through the sagebrush as we worked to keep them together. We made the eight miles to summer pasture in good time and waited an hour to make sure cows and calves had all mothered up. When the last bawling cow was quiet, we headed back to camp. It was barely noon and the drive was over. [15]

Pat later confided that he had never had a drive go so well, nor had he ever had a half day off at the end of one. Not a single cow had strayed or turned back. His compliment meant a lot. As we sat around the campfire that night, each of us had a great sense of accomplishment; it was a perfect ending to a life-changing adventure.

To learn more about Upper Canyon Outfitters, write the McDonalds at PO Box 109, Alder, MT 59710, visit www.ucomontana.com, or call 1-800-735-3973 or 406-842-5884. It’s smart to reserve your place early.

~ Ellen Baumler is the author of several award-winning books and the interpretive historian at the Montana Historical Society. Her most recent project is a collaboration with photographer, J. M. Cooper, documenting the untold history of the Montana State Prison.

Leave a Comment Here