The Capture of the Notorious Poacher Howell

Department Literary Lode

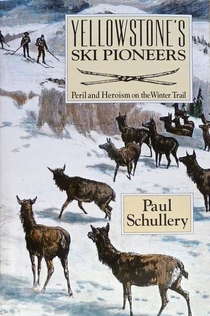

Yellowstone’s Ski Pioneers: Peril and Heroism on the Winter Trail by Paul Schullery, is a book about early skiers in Yellowstone Park, whenever possible letting the adventurers or those who patrolled the Park tell their own stories. With the aid of many sources, Paul Schullery illuminates a simpler, wilder Yellowstone.

* The following contains excerpts from the book.

It was a time of general lawlessness in the park, when careless visitors damaged many park features, and poaching was rampant during the long winters. When elk and bison were chest-deep in the deep snow, hunters and trappers could walk right up to them and shoot. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of elk, bison, and other animals were slaughtered.

In 1886 the U.S. Cavalry was assigned the protection of the park, and they took the assignment very seriously, patrolling the park throughout the year. “The scouts and soldiers who patrolled the park interior in the winter suffered extreme hardship,” historian Aubrey Haines wrote, and Schullery shows in detail the type of clothing, the skis, and the conditions they faced. The essence of the winter patrol adventure is clear in Schullery’s chapter entitled “The Capture of the Notorious Poacher Howell.”

In 1893 Howell and a companion left Cooke City and set up camp at Astringent Creek, a tributary of Pelican Creek.

The companion left but Howell remained, occasionally traveling back to Cooke City to replenish his supplies. His goal was to kill as many bison in the area that he could find and haul the trophies out for sale to taxidermists in Montana. Schullery notes that “as much as we may hate Howell’s motivations, we must admire his abilities. He dragged his supplies on a homemade toboggan ten feet long, with ski-like runners that allowed it to slide over the snow better than a flat toboggan would have. His load weighed 180 pounds.”

George Anderson. Yellowstone’s acting superintendent, was an aggressive defender of the park. Heroic as he was, he “did not have a free hand to deal with poachers. There were no meaningful penalties for poaching... All that could be done was confiscation of their gear and expulsion of the guilty party.” As for Howell, “capture was only the beginning; he had to be taken all the way to Fort Yellowstone for incarceration,

a long trip on skis with a dangerous prisoner.” In the following first-hand accounts, the participants refer to their skis as “snowshoes,” as did most people at the time.

Veteran Army Scout Felix Burgess was the man who made the capture under perilous circumstances. In Burgess’s own words:

I expect I was pretty lucky... I got out early and hit the trail not long after daybreak. After I had found the cache of heads and the tepee... I heard the shooting, six shots. The six shots killed five buffalo... When I saw him he was about 400 yds. away from the cover of timber. I knew sure I had to cross that open space. I had no rifle, but only an army revolver... You know a revolver isn’t lawfully able to hold the drop on a man as far as a rifle... His hat was sort of flapped down over his eyes, and his head was toward me.

He was leaning over, skinning on the head of one of the buffalo. His dog was curled up under the hind leg of the dead buffalo. The wind was so the dog didn’t smell me, or that would have settled it. Howell was going to kill the dog, after I took him, because the dog didn’t bark at me and warn him. I wouldn’t let him kill it...

I thought I could maybe get across without Howell seeing or hearing me, for the wind was blowing very hard. So I started over from cover, going as fast as I could travel. I found a ditch about 10 ft. wide, and you know how hard it is to make a jump with snowshoes on level ground. I had to try it anyhow, and some way I got over. I ran up to within 15ft of Howell, between him and his gun, before I called to him to throw up his hands, and that was the first he knew of any one but him being anywhere in that country.

According to a witness, the journalist Emerson Hough, Howell was “a most picturesquely ragged, dirty and unkempt looking citizen,” and apparently unworried by his capture. “He knew he could not be punished and was only anxious lest he should be detained until after the spring sheep shearing in Arizona.” He “had no shoes, and he had only a thin and worthless pair of socks. He wrapped his feet when snowshoeing into a pair of meal sacks he had nailed on to the middle of his snowshoes. The whole bundle he tied with thongs.”

Hough added that Burgess possessed “indomitable grit.” When he brought Howell in, “Burgess was limping very badly....When he got in by the fire he said nothing, but took off his heavy socks, showing a foot on which the great toe was inflamed and swollen to four times its natural size. The whole limb above was swollen and sore, with red streaks of inflammation extending up to the thigh.” Burgess had “lost the two toes next to the great toe,” and explained that the Crow Indians did that for him.” Despite that injury, “which would have disabled most men, Burgess passed the evening calmly playing whist, and the following morning again took the trail, making the twenty miles to the Post before evening, and delivering his prisoner safely. The post surgeon....at once amputated the great toe, thus finishing what the Indians had less skillfully begun some years before.

While Howell did not fade from the Yellowstone scene for many years, the results of the report on his capture were spectacular. Rep. John Lacey of Iowa introduced a bill that became known as the first “Lacey Act,” “to protect the birds and animals in Yellowstone National Park, and to punish crimes in said park.” It was hoped that poaching could completely stopped, but it still occurs infrequently even today, and modern park rangers continue to patrol the park in the best tradition of Felix Burgess and his heroic contemporaries.

Leave a Comment Here