The Devil’s Brigade in Helena

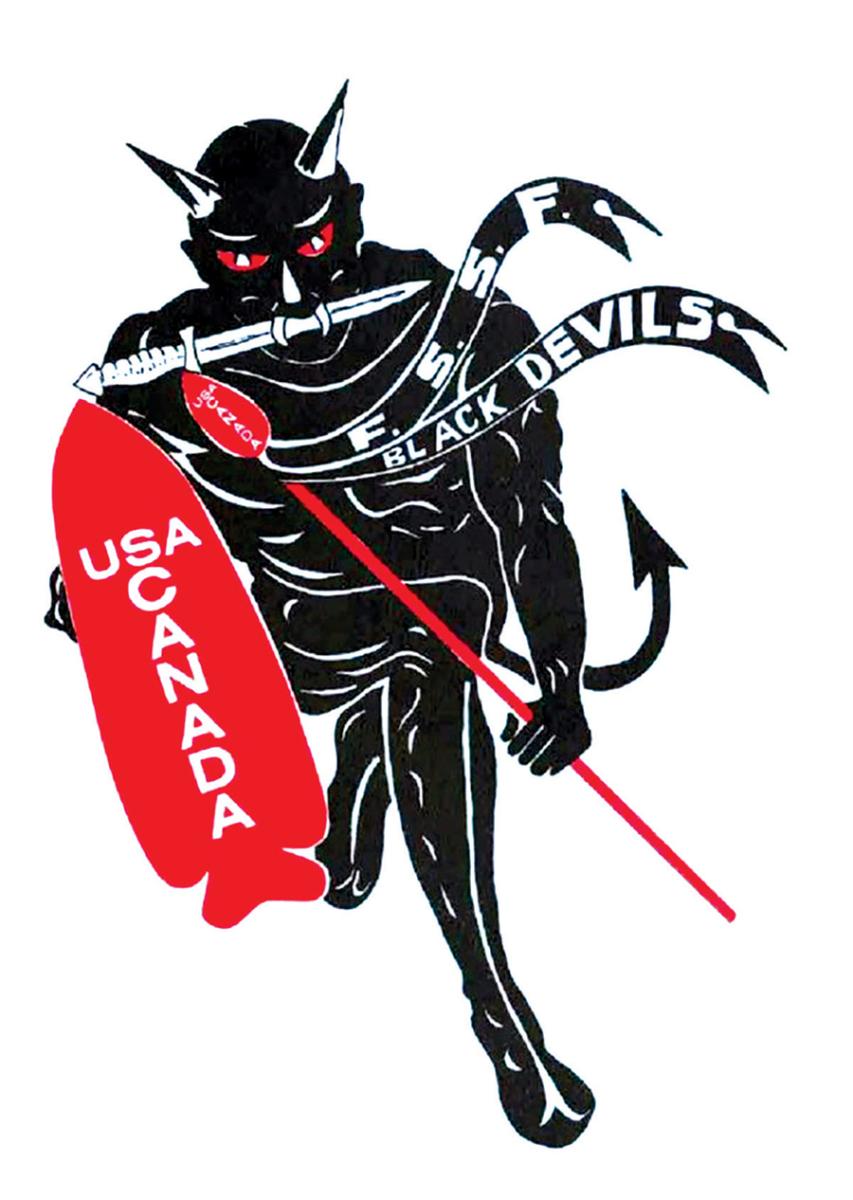

The soldiers of the Devil’s Brigade carried a very special knife. Sharp, narrow, and with a spike on the end of the handle, the weapon was designed by Lt. Col. Robert T. Frederick, a career fighting man destined to become an outsized mythical figure in World War II. Frederick had designed the knife for one purpose: to kill Nazis. His men, the 1st Special Service Force, had been trained for the same purpose by experts in hand-to-hand combat, stealth, and paratrooping. They’d been taught what parts of the body, when struck, will bleed the most—and where to stick the knife so that their adversary would die silently, choking on their blood.

The knives were stiletto-thin, able to slide between an enemy combatant’s ribs with appalling ease. But unlike traditional stilettos, sharpened only at the point, the V-42, as it was eventually named, was edged on all sides, so that it would pull through a Nazi’s throat as easily as it could pierce his steel helmet. The knife was so frightfully sharp that they had to redesign its sheath because the razor-like tips kept cutting through and nicking the men’s thighs in training. And if that weren’t lethal enough, each V-42 came with a pyramid-shaped spike on the pommel; when swung accurately and at the right angle, it wouldn’t dent a skull, it would stave one in.

The knives got plenty of use from January to June 1944, as Allied forces tried to secure Anzio. During the long and bloody engagement, Lt. Col. Frederick’s men stalked behind the enemy’s lines with blackened faces and knives clutched in their hands, on the lookout for unwary adversaries. They found plenty.

Many of the bodies of slain German soldiers had stickers affixed to them reading “Das dicke Ende kommt noch,” or, roughly, “the worst is yet to come.” One German officer stationed in Anzio wrote despairingly in his diary, later recovered, that “the Black Devils are all around us every time we come into line, and we never hear them.”

Anzio and the Italian Campaign would be a trial by fire for the young men of the Devil’s Brigade. Nor would it be their last sight of action; they would distinguish themselves as a ferocious fighting force by defending Anzio from the Axis’s attempt to recapture the city, and going on to further acts of daring and bravado in Italy and France.

But before all that, when they were just an unlikely assortment of young American and Canadian men, they trained in Fort Henry Harrison, outside of Helena, Montana. For a few months in the summer of 1942, they were Montanans.

The 1st Special Service Force, the brainchild of Britishers Lord Mountbatten and Geoffrey Pike, was conceived as a rugged and elite force that would travel through the mountains of occupied Norway, disrupting Nazi war efforts through sabotage and guerilla warfare. Their targets were to be the hydroelectric dams that supplied the majority of the country’s power—and the secondary objective was to terrorize the occupiers via stealth and hand-to-hand combat.

Helena was selected as the training site for the brigade because it offered rugged conditions that mirrored Norway’s countryside. The nearby Fort Henry Harrison offered ideal staging grounds to train in skills like skiing, mountaineering, parachute jumping and the use of explosions in sabotage. The men were also outfitted with their fearsome knife and shown how to use it. And while an excellent combat knife, the men reported it inadequate to non-combat tasks such as prying open a can of rations.

The brigade was roughly half Canadians, the result of Winston Churchill’s insistence on using men from the British Commonwealth. The Canadians were largely culled from existing Canadian fighting forces such as the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, while the United States soldiers hailed from every walk of life. They had signed up, knowing only that they were joining a force that would draw upon wilderness survival skills, and they could expect to be trained into the best of the best. Indeed, some of the Americans were troubled soldiers plucked from the brig, but the 1968 Williams Holden film adaptation of the book by Robert Adleman and Col. George Walton, which asserts that most of the Americans were criminals à la The Dirty Dozen, was inaccurate. There were school teachers, farmers, outdoorsmen—in short, anyone crazy enough to volunteer.

One young man told Frederick sheepishly that he had deserted the American Army after enlisting, secreted himself across the border, and re-enlisted in the Canadian Army instead. He wondered whether his actions might follow him here and whether he could expect a dishonorable discharge or worse. Lt. Col. Frederick looked him over and asked why he went AWOL only to sign up in a different country. Well, the soldier told him, he had joined the Canadian Army in the hope of getting to see some action against the Germans earlier that way. Frederick, satisfied, told the man he wouldn’t have to worry on either count: he’d be killing Nazis soon enough, and in exchange for his enthusiastic service in that regard, the U.S. government would absolve his guilt.

A soldier named William Story, previously a member of a Canadian choir before joining up, painted a vivid picture of Fort Henry Harrison being prepared for training:

“It was a hot and tired crew that finally pulled into the siding at Fort Harrison that August day... the camp was a cloud of dust. Bulldozers were hard at work leveling the area where the huts would go. Gangs of workmen were laying down pyramidal tent bottoms; others were erecting tents in streets. The big parachute drying towers were under construction; the mockup area, with the harness rigs, were not yet finished. Actually, nothing was finished; and much had barely begun.”

But before long, the men were jumping out of planes and learning the ins and outs of wielding their new V-42 stilettos, among other things.

While there were tensions initially, the Canadians and the Americans eventually became a group united by common purpose and even friendship. They took to swapping uniforms with each other. The Canadians preferred their American cousins’, which didn’t require polishing and somewhat resembled their officers’ uniforms. The Americans dressed as Canadians as a lark, to the confusion of base security.

The town of Helena was initially wary of the soldiers training outside their gates, especially when rumors reached them that the soldiers were miscreants gathered from the worst of the Army’s irredeemables—men so bloodthirsty they were expected to sate themselves on the villages of Axis Europe like pillaging Vikings. What the town got instead were boys and men who resembled, for all their occasional machismo, their own brothers, sweethearts, and sons.

Helena’s bars were early to adopt the boys. At joints like “the Gold Bar, the Corner, or the Log Cabin Night Club,” according to The Devil’s Brigade, forcemen could use their paratrooper’s wings as collateral for a small loan of $5, which was probably spent on booze. History doesn’t record how many wings were lost in this manner, nor how many beneficent bar owners eventually gave the wings back without collecting on the debt.

The capital city’s hotels could also find themselves besieged by soldiers in training during weekend furloughs, and in one case a soldier’s girlfriend unknowingly pulled the fuse on a dynamite cap that he had left on the hotel dresser. In a panic, and knowing that he couldn’t throw the explosive outside without killing a few Helenans, he tossed it into his hotel room’s bathtub and closed the door behind him. The explosion took out the bathroom—and the room below it—but thankfully, no one was badly hurt. The soldier and his lady friend, for their part, disappeared.

These were the exceptions that proved the rule; save for a handful of notable brawls between servicemen and miners at the Gold Bar (one thing the film more or less got right), Helena and the Devil’s Brigade regarded each other with respect and affection, despite nuisances like demolitions training. According to Ableman and Walton, “The Forcemen... often either blew up targets not on the training schedule or used twice as much dynamite as was required. These habits frequently had the result of blowing out many of the town’s plate-glass windows.” The mayor adopted the enlightened stance that Helena owed the Forcemen and, consequently, “[b]roken windows were considered one of Helena’s contributions to the war effort.”

Perhaps the tender ministrations of Helena’s women were another contribution. Some 200 of Helena’s eligible women married members of the Devil’s Brigade before they shipped out, despite, as Ableman and Walton put it, “the uncertain future that lay before such unions.”

And, of course, in addition to the marriages were the more businesslike liaisons; Ableman’s book quotes one soldier as saying, “I liked Helena and its people... [but] my acquaintance with her daughters was scant unless you counted the ones in Ida’s Rooms, etc,” he reported. Once he found that the town’s women generally preferred the Canadians, he decided that “keeping sex strictly at the animal (or supermarket) level” was best.

A soldier named Arthur Vantour painted a more picturesque portrait of love in wartime Helena: “To me the town of Helena was a wonder with all its neon lights. I could walk up and down the street at night just to be under the lights and think how the boys back home would envy me if they could see me now.” One night at the USO, enjoying coffee and donuts, he “saw a young little girl jitterbugging, as we called it in the olden days, with one of my fellow Canadian soldiers. I started doing the same and,” after marrying her, “have been dancing with her ever since.”

During their training, the men of the 1st Special Service Force didn’t know their eventual destination, although there were plenty of rumors. They knew that it involved a parachute drop, and some began to speculate that they were going to be air-dropped into Hitler’s castle stronghold.

What no one foresaw was that the plan to drop them in Norway had been abandoned, and the force was to be repurposed in the Pacific Theater, to aid in the invasion of the Aleutian Islands. In the spring of 1943, the future Devil’s Brigade was mobilized, first to Norfolk, Virginia, to finish their training, and then to the Pacific.

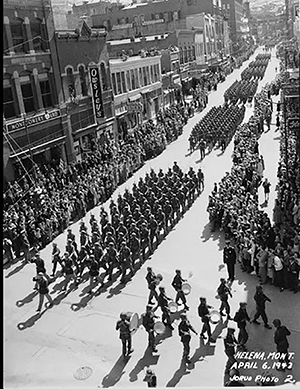

The townsfolk of Helena were heartbroken. On April 6, Adleman and Walton wrote, “the 2,300 men of the Force gathered themselves in full array and paraded through Helena, where they were reviewed by the Governor of Montana. The Helenans, who lined the street, looked as if they were watching their own sons march away.” Then they left. Their sudden absence “[left] a trail of hasty marriages and choked farewells in its wake.”

First, they arrived at the Aleutians to find the islands abandoned by the Japanese. Then they were sent to Italy, where they would engage the enemy for the first time. They never lost a battle.

At Anzio, some 1,100 forcemen would successfully defend their beachhead against 10,000 Nazis. They were so terrifying to the Germans that they issued an edict about them: “The first soldier or group of soldiers capturing one of these men will be granted a 10-day furlough.” But what was 10 days away from the front compared to an eternity in the dirt?

In their 214 days of fighting, the Devil’s Brigade would kill 12,000 Axis personnel and take 7,000 prisoners.

After the war, many of the 1st Special Services Force who had survived, like Joe Glass and Mark Radcliffe, moved back to Helena. They loved the town, or they had left wives and sweethearts there, waiting for them. They settled down. Those who stayed in Helena started families and businesses, nurtured them, and grew old with them.

Last year was the 80th anniversary of the Devil’s Brigade’s parade through Last Chance Gulch in Helena, the beautiful, almost alpine town where the men of the force first learned to kill. Today, visitors will stop and stare at their wickedly sharp knives behind glass at the Montana Historical Society Museum and the Museum at Fort Henry Harrison in Helena.

Anyone who sees the V-42 cannot help but imagine the flash of those blades in the night, the near-silent strike that pierces, kills, and withdraws into the darkness.

Leave a Comment Here