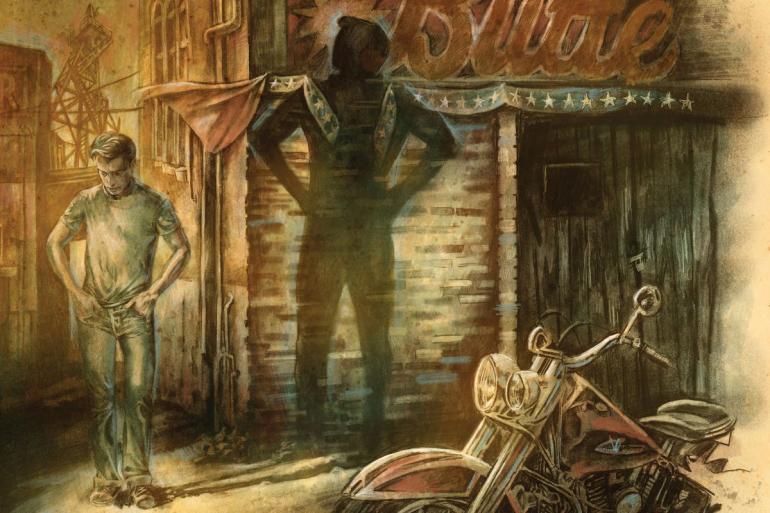

How Bobby Became a Legend

How does someone become a legend?

Buddy, if I knew, I'd be one.

How did Pecos Bill learn to rope cyclones? What possessed Robert Johnson to seek the devil at the crossroads? Why did Paul Bunyan first test the heft of an ax in his grip? These are mysteries not given to man to understand.

But, for young Bobby Knievel, petty crime was worth a shot.

Bobby had already developed a reputation by the time he was a freshman in high school.

In Butte, Montana, where he was born, you had to make your own entertainment. Many of the men chose to do so by, shall we say, socializing with ladies of the evening, a vice benevolently winked at, if not exactly condoned, by the Anaconda Mining Company, who preferred to have their vast number of working men's more violent tendencies rendered tender by the charms of the second sex—however it could be managed. This was, to be clear, still true by the early to mid-1950s, the era in which Bobby was prowling the hill on his bicycle and generally being a menace.

Bobby had another, although perhaps adjacent, way to have fun. In his own words, "when I was a kid, the main activity was to go up and throw rocks at the whores, bang on the doors, and have the pimps chase us down the street."

More or less abandoned by his parents, being raised by a saintly grandmother would only do so much to keep a boy on the straight and narrow in a town which was, as he would tell The New Yorker later, full of "pimps, hayseeds and cross-roaders."

Money, in Bobby's caclulation, would keep him away from the mines. And one quick and easy way to make a little pocket money was to scope out a new car in one of the neighborhoods of Butte and relieve it of its hubcaps. Doubling back later, he would chance to meet the owner outside.

"Hey mister, your car hasn't got hubcaps. What happened?"

He would offer help in looking for the disappearing caps. Then, inevitably, it would dawn on him that he had seen a set of hubcaps just like it at home. Maybe he'd part with them for some offered price. Most of the time, the car's owner would give him something, if not the asked price, and young Bobby would go off and return with the purloined goods. He even put the hubcaps back on himself, as a service included in the price.

When he got tired of that scam, he scaled it up and did the same thing with whole sets of tires. He also discovered that the trick was easier to pull on out-of-town marks since Buttians were more likely to recognize the con.

But then Marsh's Jewelry over on Broadway, a sturdy community pillar for years, was burgled. No one knew by whom, and the mystery had the students at the high school all riled up.

Bobby, moreover, intimated to those around him that he knew something more about the burglary than the cops, and not just through the grapevine. Those around him began to wonder: had Bobby stepped up his criminal game?

Bobby began to fish around.

"Hey, if you want to buy some jewelry cheap, I've got some I need to sell fast."

Marsh's Jewelry, as all jewelry stores do in a poor town, occupied a complicated place in Butte's psyche. It was both a symbol of everything you wanted in life—an engagement ring and wedding band for a happy marriage, a nice watch to show your long and successful career, maybe some cuff links and a suit from Wein's to go with. But on the other hand, if you weren't someone who had a lot of money, which was most of the town, you might regard those very same baubles with something like jealousy.

It might also bear pointing out that, as Bobby's biographer Ace Collins wrote, Butte was, at that time, "a town where many still thought of Bonnie and Clyde and Pretty Boy Floyd as American heroes."

Which is to say yes, there were people would wanted to buy the jewelry cheap. One by one, or even a few at a time, Bobby divested himself of bracelets and necklaces, selling them to friends and acquaintances who appreciated a good deal. It only added to the frisson of owning them that they were, in the parlance, hot.

And then, Bobby's supply of jewelry dried up, and he stopped insinuating he knew anything about the jewelry store heist. It was only a short while after, as everyone got home with their new riches and inspected them a little closer, that they realized something wasn't right.

Ole Bobby hadn't burgled the store at all. What he had done was to go buy up a bunch of costume jewelry as soon as he heard that Marsh's Jewelry had been robbed.

But how did otherwise grounded Butte folks confuse cheap dime store trash with the kind of haute bijouterie offered by Marsh's Jewelry? You may as well ask how just a few short years later, at the age of 24, he managed to sell 271 insurance policies [SP2] to not only the staff but also the residents, too, of Warm Springs State Hospital? Hell, you might as well ask how he managed to jump fourteen (!) Greyhound buses at the Ohio's King's Island Theme Park.

In other words, it's not given to us to understand how legends perform their feats.

Bobby dropped out of high school at 16 and, using his hubcap and jewelry store money, he got his first motorcycle. Or rather, his first purchased motorcycle, since he had previously been arrested for stealing one at 13. Within minutes of his purchase, he was zipping down the hill and through city streets going much too fast.

Then he collided with a parked car, sending him over the handlebars and onto the pavement. The motorcycle skidded into the curb and burst into flames. Bobby's leg broke, and for the first time, but certainly not the last time, Bobby was lucky to be alive. Unrepentant, perversely obstinant in the way that only Butte can be, Bobby bought another bike as soon as he could and took to racing the police around the town, popping wheelies and raising hell.

On one of his run-ins with the cops, he was jailed next to the notorious criminal William "Awful" Knofel, suspected at one time of the murder of the 80-year-old Butte laundry owner named Quong On. The cops knew Knofel, as they knew Bobby. They liked Bobby only slightly better than Knofel, whom they'd nicknamed Awful.

"Well, what do you know," one of the cops said that night, a grin on his face. "We've got Awful Knofel, and Evil Knievel! How do you like that?"

In the end, Bobby liked it well enough. It sounded legendary.

Leave a Comment Here