The Ice Busters

Aerial Bombardment of the Miles City Ice Jam on March 21, 1944: The Only Sortie Flown by American Military Aircraft Against a Target on American Soil During World War II

From the lowest temperature (-69.7°F) ever recorded in the contiguous United States, which was observed on January 20, 1954, to a 103°F temperature increase that spanned portions of January 14-15, 1972, Big Sky Country has set the standard for a host of extreme-weather categories. Other examples of Montana's volatility include a bone-chilling 100°F temperature drop that transpired over 18 hours on January 23-24, 1916, and powerful Chinook winds which, in winter, relentlessly bombard the Rocky Mountain Front, as well as unseasonably severe blizzards. However, one aspect of the Treasure State's meteorological legacy is less widely recognized.

According to Todd Chambers, a meteorologist for the National Weather Service, "Montana has the highest number of reported ice jams and ice jam-related deaths in the lower 48 states." Freeze-up jams, which typically occur during early- and mid-winter, pose little threat to life or property. Most ice jams, however, happen when river ice thaws in response to the warming temperatures of late winter and early spring. Indeed, meteorologist Mitchel Coombs states that "Nearly a third of all ice jams occur in the month of March."

Ice floes generated by "breakup jams" become most problematic when they congregate near riverbends, mouths of tributaries, and areas where river gradients decrease. Unfortunately, breakup jams are virtually unpreventable and can trigger dangerous flooding. Ice jams that are large enough to obstruct streams as wide as the Yellowstone can, as Chambers observes, cause water levels to rise at rates up to "a foot an hour."

A report by Tony Thatcher and Karin Boyd (2008) corroborates the occurrence of more than 100 ice jams on the Yellowstone River between 1894 and 2007. Areas surrounding Miles City are notoriously prone to their development, as evidenced by 23 ice jams on adjoining portions of the Yellowstone from 1934 to 1997, and 17 more reported at the Tongue River Station between 1947 and 2003.

The most significant of these events occurred in 1944. Although the weekend of March 17-18 began unremarkably, civilian authorities and first responders had, by late Sunday evening, begun to implement evacuation procedures, which impacted 300-500 residents, in response to the ominous threat of rapidly rising waters. According to an article published in the Missoula Current, the Yellowstone crested at "19.3 feet, 3.3 feet [above flood level] and about 15 feet higher than normal." Water levels on the Tongue River, which were "about 12 feet higher than normal," forced ice floes over Twelve-Mile Dam and exacerbated flooding of the Yellowstone.

On Monday, March 20, Leighton Keye, mayor of Miles City, enlisted the services of local pilots to bombard the Yellowstone ice jam with improvised explosives. Fred Cook, Ted Filbrandt, and Leighton "Brud" Foster dropped homemade bombs, constructed from 1,500 pounds of dynamite, from their Piper Cubs. The surface-level detonation of these devices provided no relief from the imminent catastrophe that confronted Miles City. Consequently, Keye contacted Sam Ford, governor of Montana, with a simple request: "Send in the bombers."

Events on March 21, 1944, constitute one of the most unique episodes in Montana history, which Gary Coffrin properly contextualizes as "the ONLY domestic bombing mission ordered by the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II." Primary-source accounts from crew members, recorded decades after this incident, provide operational details that were not presented in contemporary newspaper coverage. According to an article published by his niece in 2009, Major Ezzard (1916-2008) received a 9:00 a.m. telephone call from Second Air Force headquarters at Colorado Springs, Colorado. Then director of B-17 combat crew training at Rapid City Army Air Base, Ezzard was initially tasked with delivering the requisite ordnance to destroy the Yellowstone ice jam.

Ezzard's crew encountered blizzard conditions throughout significant portions of their flight to Miles City. Indeed, Earl Tagge, a 20-year-old staff sergeant from North Platte, Nebraska, later recalled that "We had to fly by instruments for about the first half-hour because we couldn't see out of the cockpit." Inclement weather and persistent low cloud cover contributed to revision of the operational plan, which called for transfer of ordnance from Ezzard's B-17 to an army dive bomber that was scheduled to arrive from Bruning, Nebraska. That aircraft never materialized. According to his niece, Ezzard was then told to "use his own judgment—bomb the river if he thought he could or forget the mission and return to Rapid City."

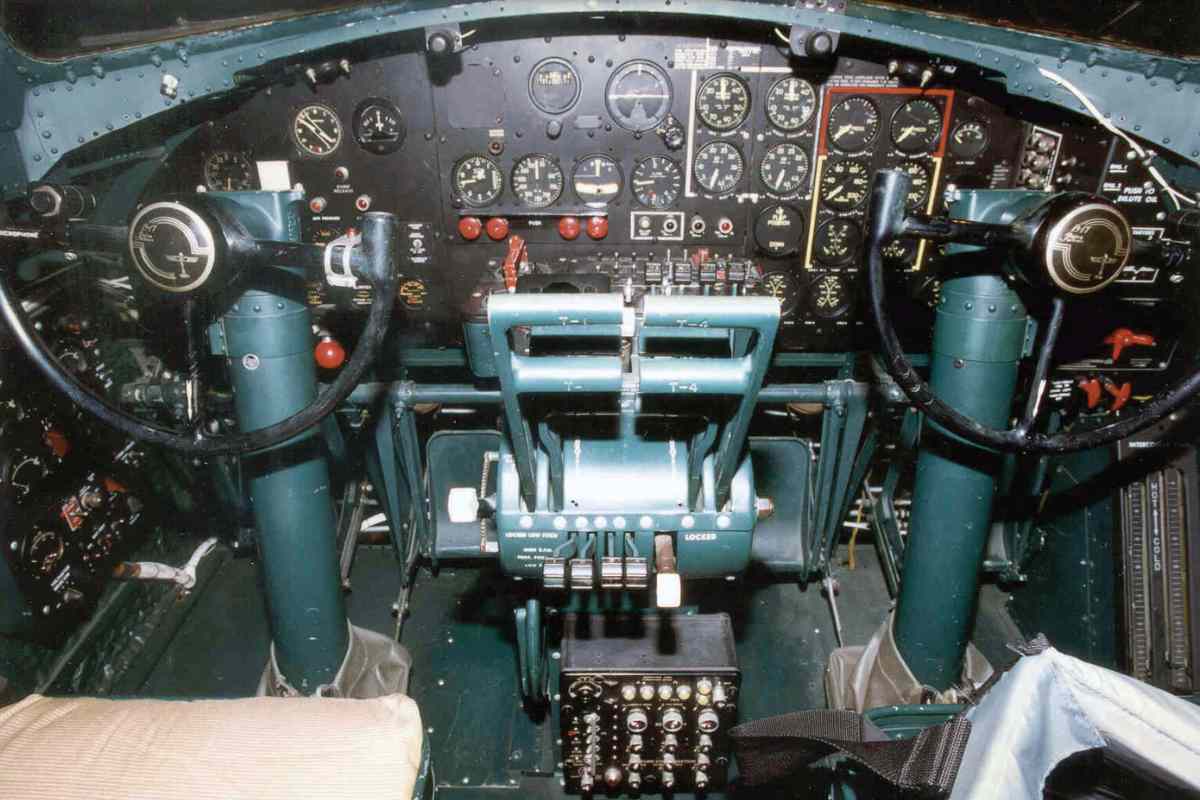

Published accounts generally concur that aerial bombardment of the ice jam commenced at approximately 7:30 p.m. and was conducted at an altitude of 2,200 to 2,600 feet. An article published in The Billings Gazette on March 22nd specifically indicates that sixteen "250-pound bombs [were dropped] along a five-mile ice gorge." Destruction of a target that large by one bomber with conventional ordnance would, presumably, have required strategic use of the intervalometer.

Better known as a bomb-release control, these devices enabled bombardiers to regulate the number of bombs dropped per release and, for a given airspeed, their spatial patterning. For example, type B-2A intervalometers, which were commonly employed on B-17s, afforded great flexibility in selecting the number of bombs released at one time (from zero to 50) and the impact distance between bombs (seven to 750 feet).

According to Staff Sergeant Tagge, Ezzard's crew conducted three bomb runs. The first deployed one bomb as a test, just downstream from the Seventh Street bridge, followed by two runs in which six bombs were dropped on each pass. Tagge emphasizes that these bombs were "triggered to detonate underwater." Subsequent explosions produced loud "whooshes" and eruptive columns of mud, water and ice that swirled upward to, perhaps, 150 feet in the air.

The ice jam began to break apart in the next hour, much to the relief of hundreds of onlookers and a radio audience that listened intently to Ian Elliot's live coverage of the event, which was broadcast from atop Garfield School on KRJF, 1340 AM. Normal water flow resumed soon thereafter, which resulted in a 10-foot drop in water levels over the next 24 hours.

Efforts to identify the specific aircraft used in the Miles City mission are promising but inconclusive. Records indicate that Ezzard piloted at least two B-17s on combat missions in and around Java, Australia, and New Guinea. The most legitimate candidate for this accolade is a B-17F (Number 41-24401), nicknamed "Lak-A-Nookie," which Ezzard flew in a night mission on October 31, 1942. This sortie was one of 50 conducted by its crew(s) before redeployment to the United States on October 21, 1943.

During the following year, this aircraft was stationed at Rapid City Army Air Base, where it was photographed in early 1944, with the crew of 1st Lt. Victor E. Stoll. Quite simply, this bomber was in the right place at the right time, and it was used to train B-17 crews prior to their deployment as part of the 8th Air Force in England. However, available evidence does not categorically prove that it was the instrument of destruction in this legendary raid.

According to Margaret Ezzard Tyndall, his niece, Major Ezzard was promoted to lieutenant colonel 10 days after completion of the Miles City mission. In remarks delivered during a Memorial Day speech in 1996, he quipped that his promotion "would not have occurred, had he hit anything but the river." Ezzard was ultimately awarded the Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, and Air Medal with one oak leaf cluster before his retirement in 1966 at the rank of colonel. He was, indeed, the only World War II bomber pilot who had the honor and distinction of defending our country in the homeland, albeit against an incursion by Mother Nature, rather than a foreign invader.

The Miles City mission was, perhaps even from his perspective, the pinnacle of Ezzard's distinguished 27-year (1939-1966) career in the Air Force. However, for readers who prefer, on occasion, to interpret the course of history through a philosophical or providential lens, two preceding events are particularly noteworthy.

At 10:10 p.m. (Pacific Time), on December 6, 1941, then-1st Lt. Ezzard embarked on what was scheduled to be a 14-hour, 2,400-mile flight from Hamilton Field, near San Francisco Bay, to Hickam Field in Hawaii. Approximately two hours later, Ezzard reported engine trouble and returned to California. If he had not experienced mechanical problems, his crew would have flown into the same firestorm that met 12 B-17s en route to Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941.

Hopelessly outnumbered, virtually out of fuel, and unarmed, they flew straight into the teeth of a Japanese strike force, which, in its two waves, contained 353 aircraft, including 79 fighters. Miraculously, all 12 B-17s successfully landed, although one (Number 40-2074) became, in the words of co-pilot Ernest Reid, "the first US airplane crew shot down in World War II." Its fuselage, engulfed in flames after a hail of bullets hit a locker full of magnesium flares, broke in half moments after touching down on the runway at Hickam Field.

For reasons that remain inexplicable, then-Captain Ezzard also escaped death on March 12, 1943. Orders were dispatched for the delivery of a B-17F (Number 42-29532) from Smoky Hill Air Field (Salina, Kansas) to Morrison Field in West Palm Beach, Florida. Service records for this aircraft clearly indicate that it was a structural "lemon," virtually from the time it rolled off Boeing's assembly line in Seattle. Indeed, it was formally condemned, i.e., classified as unserviceable and not reparable, the day before its fateful flight. Two hours and 35 minutes after departure, this flying coffin crashed nine miles north of Sheridan, Arkansas, with no survivors.

Chillingly, Ezzard was ordered to accompany the crew on this flight as a passenger, perhaps to monitor the plane's in-flight performance. In an incident report (2012) on this fatal crash, Nelson Mears concluded that "It is a 'mystery' why these four officers were ordered and another 'mystery' as to why they were not on board the plane when it crashed." Had either of these scenarios unfolded differently or a pilot and crew as competent as the one led by Ezzard was not available, we might recall this ice jam as a far more catastrophic chapter in Montana history. Fortunately, residents of Miles City were spared from that fate.

Leave a Comment Here