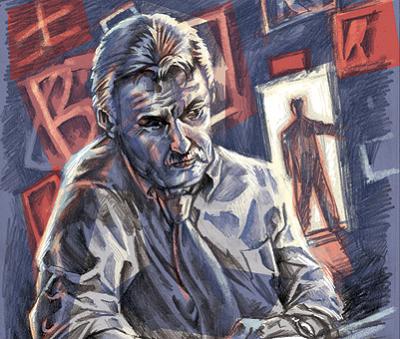

The Right Madness

Editor’s note: Crumley dedicated this book to his hometown, Missoula. In the opening chapter, Sughrue, a retired detective, meets his friend, Dr. Will MacKinderick, a psychiatrist, at the Depot bar. MacKinderick is convinced one of his patients has stolen files from his office, and he begs the reluctant Sughrue to investigate for a price the desperate private eye can’t refuse. Things quickly spiral out of control, as you will see in this book excerpt. Crumley, who died in 2008, was considered one of the best and most popular hardboiled crime writers in the country. His main character, Sughrue, carries a lot of scars...

People have a lot of theories about life — what it means, how to survive it, and other unadulterated bullshit. The only thing I’ve ever heard that made any sense came many years ago and in a country far away, not on some windswept mountaintop but among the crumbling sandbags of a night defensive position, and my guru wasn’t some bearded, balding wise man but a giant Hawaiian-Black-Mexican M60 gunner in the middle of his second tour in Vietnam.

Because my job as a private investigator lent itself more toward the mundane and realistic, I didn’t have much use for theory, but it was a fine late-summer morning in the Winding Woods neighborhood of Meriwether, Montana, and I was lulled into aimless illusions of theory as I carried a clipboard and wore a fake name tag on my short-sleeved white shirt that identified me as JOE DON LOONY, REAL ESTATE AGENT, ostensibly checking for somebody who wanted to sell his house in the old neighborhood, but actually working a job I didn’t much care for, the crazy chore for my old buddy Dr. William MacKinderick, when Nacho’s dark face suddenly rose before me, not like a flashback — I knew about those — or a nightmare, just a sudden solid vision out of my past, a moment of unexpected laughter.

The past hit me in the face like a bloody hand. Back during the Vietnam War, Nacho and I had survived a bad day in the bush. My first one, really. We had nearly lost a reinforced platoon patrol through the usual stupidity and lack of leadership. All of our officers were new guys getting their tickets punched in the combat zone, and most of the experienced NCOs were back at the base camp club or drunk in Bangkok. The company commander, a young first lieutenant, was an ROTC jerk from Georgia. An NVA company was cleaning our plows — 30 percent casualties in ten minutes — and we would have gone the way of that idiot Custer if a passing flight of Cobra gunships that had been fogged out of their mission hadn’t been close enough to save our badly charred bacon. Their rockets and miniguns cleaned the NVA off the ridge top, flattened the hidden encampment, and showed me what hell really looked like.

When it was over, it was too late to extract anybody but the dead and wounded, so we set up a night defensive position on the ridge line. Just before good dark, Nacho calmly stirred coffee over a burning scrap of C4. My hands were still shaking so badly that I had trouble holding my cup still when he asked me how I liked my baptism of fire.

“Jesus, we were lucky,” I said breathlessly.

He laughed, then reached over to poke his finger through a hole in the pocket of my fatigues. “Hey, man, look at it this way,” he said, still chuckling, “fistfights, firefights, and fucking love affairs — nothing counts but luck and geography, man.” Then he tugged on the bullet hole, laughing even harder as I shit my pants. Again. “Luck and geography.”

For me it was laugh or cry, or some of both.

I didn’t have much to laugh about, exactly, now or then. I already missed my wife. But it was my fault. I had refused to even consider moving with her a thousand miles away to Minneapolis, where she had taken a job at a high-powered firm in the Twin Cities. She was still miffed that I refused to go back to law school, and if that wasn’t bad enough, she had also taken my son with her. Insult to injury, as they say. And I’d been having endless nightmares since the day they left...

Surveillance is never as easy as it looks in the movies, and working a one-man job in a small city like Meriwether made it that much harder.... I rented an anonymous Taurus sedan, equipped it with my handheld police scanner and cell phone, added a small pair of binoculars and the Leica 35-mm camera with the 150-mm telephoto lens, a bouquet of gimme caps, a selection of windbreakers, and a couple pairs of sunglasses, and I was ready: your average, run-of-the-mill, hardworking private investigator perfectly equipped to track a bunch of Dr. MacKinderick’s neurotics around town.

Mac’s patient list was organized by appointment times instead of the alphabet, with one name on each page. I assumed that meant something so I didn’t bother looking beyond the first name on the list. And it was one I knew, as Mac said might happen. The background on this guy was pretty easy. I just hung around the college bars for a couple of nights posing as a retired English professor on vacation, logging a half-dozen expensive hours and picking up gossip.

Professor Garfield Ritter saw Mac at 8:00 a.m. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Ritter had been chairman of the English Department at Mountain States since gasoline was eighty-nine cents a gallon. Ritter had come west with this Yale Ph.D., shoulder-length curly hair that went with his politics, and a bellyful of academic ambition. Twenty-five years later, the hair, like the politics, had disappeared; none of his scholarly papers had ever been published; and now he had the belly of a Republican banker with the only fire inside his spastic colitis, caused, perhaps, by his fat, rich Main Line Philadelphia wife, Charity, who by all accounts had none and was reputed, when drunk, to be meaner than a tow sack full of drowning cats.

The Ritters lived in a large restored Victorian in the Winding Woods neighborhood south of the Meriwether River, a collection of winding streets that often fooled even the natives. By nine o’clock that Wednesday morning I was parked and ready. Except for a pair of house painters struggling down the street with their scaffolding toward the Ritter’s neighborhood, the streets were empty. I started out going through the motions: carrying my clipboard around and asking dumb questions, waiting for Ritter to come home after his appointment with Mac and before he went back to the college for his eleven o’clock office hours. I thought I would see what the professor did with his free time between nine and seven.

Around a quarter to ten, as far as I could tell, Ritter still hadn’t shown up. I walked up to the door of his house, picked up the rolled paper on the steps, and rang the bell. It seemed that I could hear distant chimes through the thick oak door, but I wasn’t sure. After a bit, I rang again, waited, then knocked. The heavy doors unlocked, swung open slowly. Nobody answered my “Anybody home?” shout, either.

I glanced at the alarm keypad and the security company sticker below it. I suddenly felt very exposed. I dropped the newspaper, trotted to the rent car, and moved it to a wandering cross street where I could see the front door. All the way, I told myself that nothing was wrong, that I was just unsettled, perhaps even slightly nervous because this case seemed so ambiguous from the beginning. I’d always been better at finding people than following them. I also know better than to work for friends. The longer I looked at the open door, the more it bothered me.

I called the Ritter residence several times on the cell phone, without an answer. The professor didn’t answer his office telephone, either. So I called Mac on the hour.

“What’s going on?”

“Did Ritter show up for his appointment this morning?”

“Of course, why?”

“How did he seem?”

“Fine, why?”

“The front door of his house is open,” I said.

“Oh, hell,” Mac said. “I know his wife’s at home. He told me they had words this morning. But they have words almost every morning with their bran flakes.”

“And you can’t tell me what they were, right?”

“ I can tell you that they were just the usual, nothing out of the ordinary,” he said.

“Look, buddy, I’ve got a bad feeling about this,” I said. “We’ve got three choices. I can go in and out like a cat burglar, and if nothing is wrong, we’re cool. Or I can place an anonymous call to the alarm company. Or the police.”

“What do you think?”

“He forgot to lock the door on his way out,” I said, “and she’s sleeping one off. Except...”

“Except what?”

“They’ve got a three-car garage, so he probably went out that way,” I said. “And rumor has it that she has her first vodka of the day with the morning paper.”

“And the paper is still on the front steps?”

“You got it,” I said.

“You better check it out,” he said without further explanation.

“Be prepared, Mac,” I said.

But no one could have been prepared for this. The double front doors opened directly into the bright light of a large atrium formed by a skylight cut through the attic and the roof above, with living and dining rooms and library set off to the sides, the kitchen at the end, and a wide stairway on the right leading to a balcony. But I didn’t know that then. That information all came later. As I stepped across the threshold, I heard a strangled scream from above. Through the flood of sunlight pouring into the atrium, I glimpsed a pale shape teetering on the balcony rail, a flash of light behind her — Mrs. Ritter in a white nightgown and robe, I later learned — then the figure screamed and swooped down toward me.

To learn what happens next read the novel The Right Madness published by Viking, 2005. You may get turned on to other James Crumley novels.~ Editor

Leave a Comment Here