Who Built Montana’s Mansions

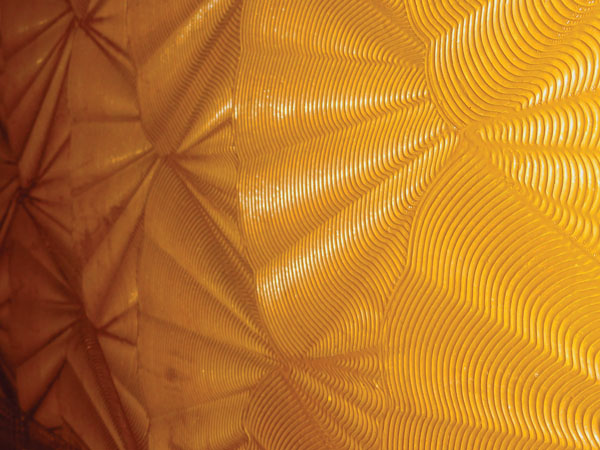

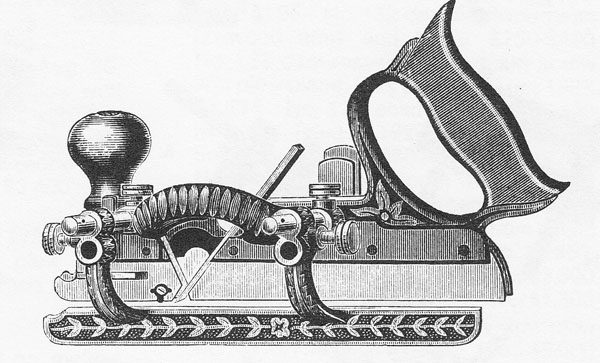

Wealthy businessman Marcus Daly did not build the Daly Mansion in Hamilton. His rival, William C. Clark did not build the Copper King Mansion in Butte. Nor can Nelson Story, C. E. Conrad, Preston B. Moss or Conrad Kohrs make that claim for impressive historic homes in Bozeman, Kalispell, Billings, and Deer Lodge. Yet their names adorn the mansions which thousands of visitors tour every year. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that their money built the homes, but money can’t hold a hammer. Cold cash can’t lay thousands of bricks or decorate a wall with elaborately combed plaster.

Skilled craftsmen built these homes.

Technically, one of the first private homes in Montana was built in Washington Territory. Then from March, 1863, to May, 1864, it was in Idaho Territory. At that time, John F. Grant, son of a Hudson’s Bay Company agent, was living in a rough cottonwood shack at the north end of the Deer Lodge Valley, near present-day Garrison. He was approached by two men who asked if he would like a hewed log house. When he asked who they were and where they came from, one replied his name was Joe Prudhomme and he and his companion had deserted from Fort Benton Trading Post. As Grant observed later, “It seemed a poor recommendation, but it was honest.”

Prudhomme and his partner built the house, and though it was no mansion, it was one of the earliest contracting jobs in what is now Montana. Prudhomme’s name appears occasionally in early newspapers, most frequently describing him as a mountain man and gold seeker. Like many others, he drifted on.

In his memoir, Johnny Grant recalled that two years later he gave that house away and wrote, “In the fall of 1862, I built a house in Cottonwood, afterwards called Deer Lodge. It cost me a pretty penny…I paid five dollars a day to McLeod, the hewer; and to the carpenter, Alexander Pambrun, I paid nine dollars a day.

Along with thousands of others, Pambrun came to Montana during the gold rush. Like them, he turned to other work when gold proved elusive. Many a Montana fortune was made by such men who found that real wealth in a gold camp was to be made by “mining the miners.” He built Grant’s new home in the style he had seen at Fort Vancouver, Washington, as a youngster.

Two years later, Grant hired Louis LaFrance to do the finish work on the house, including windows, doors, locks and hinges which arrived in the territory by steamboat from St. Louis, Missouri.

Though still a far cry from the mansions of Montana’s mining heyday, it was lauded in the Virginia City newspaper in 1865 as “by long odds the finest in Montana. It appears as if it had been lifted by the chimneys from the bank of the St. Lawrence, and dropped down in Deer Lodge Valley.”

In 1866, Grant sold out to rising cattle baron Conrad Kohrs. By the time Kohrs more than doubled the size of the home to 8,800 square feet in 1890, the sort of credit which Grant had given in his memoir was harder to come by. In his autobiography, Kohrs simply states “we began remodeling and putting an addition to our house.”

Fortunately, due credit can still be given to individual craftsmen because Kohrs meticulously recorded the names and wages in his ledger. H. B. Ross, W. Law, L.C. Bradshaw and Sam McCurdy did carpentry. Charles Forest laid some of the nearly 40,000 bricks of the new addition. Edmonson and Mandinger did stone flagging. Keiser and Streacher painted. John Ward was a stone cutter. Christian Schurch, a Swiss immigrant was a tinner who installed the gaslight system: Just a handful of names out of the thousands of men whose skill and labor created the built legacy of Montana.

Between the 1862 Grant home and the 1890 Kohrs addition, men made fortunes raising cattle, investing in mines and serving or cheating the government.

Nelson Story had a mansion built in Bozeman which included copper cornices, cherry, black walnut and maple paneling. Kasota sandstone was brought from Minnesota, along with a contingent of stone masons from St. Paul. Don’t look for those features in the Story Mansion in which graces Bozeman today. They were part of his first Bozeman mansion, long since torn down.

The Montana Historical Society Web site notes “Entrepreneur William Chessman built the original Governor’s Mansion as a private residence in 1888.” In 1891, he was found guilty of misusing funds from an estate of which he was executor. The judgment against him amounted to nearly $200,000 dollars. In that decade, bricklayers were typically receiving $5.00 to $6.00 per day; stone-masons, $5,00, plasterers, $6.00, carpenters, $3.50 to $5.00. It’s not hard to imagine the sorts of comments Chessman’s former workmen might have made upon reading that bit of news. Still, they could take renewed pride in their work when it became the Governor’s Mansion in 1913.

As businessmen prospered and communities grew, workmen came to be overseen by a builder who, himself, might be overseen by a general contractor. With even greater prosperity, a qualified architect often created yet another layer between the owner and the workers.

“In 1903, entrepreneur Preston Boyd Moss (better known as “P.B.”) built the Moss mansion.” So reads the introduction to the history of the impressive Moss Mansion in Billings. By then, it had become almost customary for Montana’s wealthy citizens to bring in noted architects to design their homes. Moss engaged Henry J. Hardenbergh, among whose other works was New York City’s famous Plaza Hotel. The masons, carpenters and others who did the actual building may never even have seen him, but it is possible they appreciated something they had in common: Hardenbergh designed for structural integrity, not simply a showy façade. That sort of integrity is important to skilled craftsmen who find a lasting reward for their work in the way it stands the test of time.

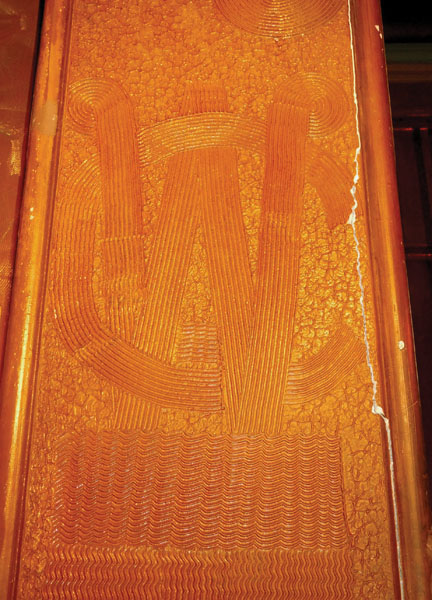

Justly proud of their skills, some men found very private ways to take a little credit for their work. Penciled inside attics, closets and framing, scratched into concrete, written across walls and immediately hidden by a layer of paint are names and dates — never, perhaps to be seen, but a bit of secret satisfaction to the craftsmen.

Daly, Conrad, Clark and all the other well-known names of Montana’s history are gone. Their power and wealth are no longer theirs to wield. But mansions, courthouses, schools, bungalows, churches, and businesses still stand as a testament to the men who built them.

- Reply

Permalink