Historic Homesteads

Feast or Famine...

In the dark, early years of conflict between the Northern and Southern States, when Civil War threatened to forever shatter all that the founding fathers had created, Abraham Lincoln signed a momentous piece of legislation. The Homestead Act of 1862 had little to do with the Civil War—at least not directly—but, like the War itself, it would dramatically shape the future destiny of the nation. Especially affected was the American West, and most notably, the soon-to-be-formed Territory of Montana. It would ultimately become the most heavily homesteaded state in America.

Under the original Homestead Act heads of family could claim 160 acres of contiguous government land. To be eligible, an applicant had to be twenty-one years of age, as well as a U.S. citizen, or an alien who had filed for citizenship. Applicants had to live on the homestead for five years and make certain improvements to gain title to the land.

The prospects of settling on tracts of essentially free land—like the gold rush—drew the ambitious westward. Even as the Civil War experienced its violent death throes in the East, the Montana Post observed that the Territory’s fertile, well-watered western valleys were “fast being settled up with farmers, many of whom came to Montana as a better class of miners and, after quitting their original pursuits, secure 160 acres of land . . . and go to work in true farmer fashion.”

Montana’s early homesteaders settled in remote but scenic places, such as the Madison, Gallatin, Deer Lodge, Prickly Pear, and Bitterroot Valleys. There, by selectively irrigating and protecting crops against the late spring and early autumn frosts, they produced the fine harvests of grains, vegetables, and fruits that fed the ravenous mining camps of the northern Rockies.

Though their numbers were initially few, and their lives were unquestionably difficult, many of Montana’s first generation of homesteaders clearly recognized that land was the key to stakeholdership in the great American dream. They understood that with land ownership came a level of independence, stability, and opportunity that the vast majority of late nineteenth-century Americans craved. In numerous letters to friends and family back East their optimism and confidence was unmistakable.

“I think I have as good a stock farm as there is anywhere,” wrote Joseph Bumby from Silver Star, Montana, in May of 1871. “It is a beautiful place here in pleasant weather, thousands of acres of thick, green, luxuriant bunch grass . . . all around you with the thickly wooded snow capped mountains in the distance . . . Sometimes I get almost discouraged, here all alone, camping out amongst the wild beasts, without any fence around my grain, at present . . . I have more to do than one person can attend to . . . but I am in strong hopes of making a good farm here . . .”

While homesteading typically offered settlers a more secure future than the area’s boom-bust gold camps, farming in Montana initially remained limited. Aridity, a pervasive get-rich-quick mentality, and still-enormous Indian reservations combined to restrain the homesteader’s progress during the latter 1800s. With the long-awaited arrival of the railroads, a handful of sodbusters irrigated bottomlands along the Yellowstone, Missouri, and Milk Rivers, and a few even tried dry farming on the bench lands of northern and central Montana. But as the 20th century dawned, the eastern two-thirds of Montana remained essentially a wide open expanse of vacant public land. All that would soon change.

In the years following the Civil War, America’s Industrial Revolution set the stage for a pronounced agricultural transformation in Montana and elsewhere during the early 20th century. Steam and gas tractors, steel moldboard plows, and steam-powered threshers now afforded the homesteader the means to farm far more efficiently, and on a more profitable scale, than in the horse and hand plow days. The industrial age had also created hungry urban populations and offered railways that conveniently connected Montana to those burgeoning markets. Land grant colleges and agricultural experiment stations simultaneously promoted a plethora of new-fangled dry land farming techniques.

Coupled with these long-developing trends were several short-term causes that ultimately triggered Montana’s remarkable homestead boom. The most significant was the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909, which doubled the free land available to settlers to 320 acres. In 1912, Congress went even farther, lowering the required waiting period for land acquisition from five to three years, while also permitting homesteaders to be absent from their lands five months of each year. Together, these laws generated an eager response, ensuring that nearly thirty-two million acres of Montana land would pass from public to private hands.

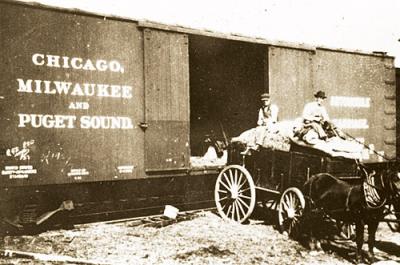

Equally significant in attracting homesteaders were the aggressive promotional campaigns by area boosters. During the early 1900s, transcontinentals like the Northern Pacific, the Great Northern, and the Milwaukee Road spent millions publicizing the region. With impressive agricultural display trains and a host of colorful leaflets and brochures, they encouraged immigrants—especially Germans and Scandinavians—to embrace a new life of farming in what some now evocatively billed as “the Treasure State.” For as little as $22.50, a homesteader could rent a freight car to bring his family and all their belongings from Saint Paul to eastern Montana.

Hypnotized by the powerful sway of a well-financed propaganda machine, homesteaders flooded into Montana. Between 1900 and 1909, a veritable tsunami of settlement descended upon the state, rushing westward across the High Line area north of the Missouri River and engulfing the broad valleys that fed the Yellowstone River. Dozens of new boomtowns, like Wolf Point, Glasgow, Malta, Havre, Plentywood, Scobey, Jordan, Rudyard, Ryegate, and Baker appeared out of thin, dry air, like mirages on the rolling plains.

Homestead life was anything but easy. Many newcomers erected sod houses constructed from grassy slabs of topsoil. Others built cramped, one-room shanties out of rough-cut lumber, covering them in tarpaper, and insulating them with dirty rags and discarded newspapers. Mice, snakes, and grasshoppers were a constant torment. Some families traveled up to 25 miles to cut fence posts, find firewood or dig coal on the prairies of eastern Montana. With these crude accommodations, homesteaders faced the blistering heat, choking dust storms, and subzero cold of Montana’s often-inhospitable plains.

Isolation on this harsh and forlorn landscape often took its toll. “I have stood in the doorway of our shack, with my heart full of sadness and loneliness, and listened to the wind,” wrote Sue Howells of Choteau County. “It is an incessant, screeching, whining and screaming wind and it seems to be heard nowhere except in Montana on the homestead.”

Despite these hardships, many carved out a meaningful life during Montana’s homestead boom, and the effects of their commitment were readily apparent. The state’s population exploded from 243,329 to 376,053 and the aggregate number of farms doubled to 26,214 during the 20th century’s first decade. By 1910, the income generated by agriculture surpassed that of mining. But this was just the beginning.

In the years immediately following this initial burst of excitement, nature and global politics work hand in hand to beguile even more homesteaders to the Big Sky Country. The period of greatest settlement during the homestead boom was also a time of generally ample and well-timed rainfall in typically drought-stricken northern and eastern Montana. Abundant wheat harvests were commonplace. In 1909, total wheat production reached almost eleven million bushels, but in the “miracle year” of 1915, it totaled more that forty-two million bushels.

Making homestead life even more prosperous was the coming of the “War to End All Wars,” which ravaged Europe between 1914 and 1918. World War I dramatically increased European demands and artificially inflated grain prices to unprecedented levels, and Montana’s high protein hard spring and winter wheat “held top rank on the booming international markets,” according to historians Michael Malone and Richard Roeder.

The future seemed especially promising: so much so, in fact, that most Montana homesteaders readily heeded the calls by government officials and bankers to “do their patriotic duty” and reinvest their profits in more land and machinery. “Food will Win the War!” the era’s propaganda posters proclaimed, and with readily available credit, Montana’s homesteaders mortgaged virtually everything in hopes of cashing in on the soaring economy.

By Armistice Day in 1918, the state’s population had climbed to an astounding 769,590, according to one governmental publication. Remarkably, Montana’s population had more than tripled in less than twenty years, and with this wave of settlement, hundreds of new towns and no less than twenty-eight new counties had been created.

The growth that occurred during Montana’s homestead boom was so pronounced, and so astounding, that when it all came crashing down, the enormity of the tragedy was almost incomprehensible. The bust’s beginnings were hardly noticeable. The rain stopped falling in the spring of 1917 in isolated places in northern Montana. Heat waves baked the brown earth black. Then the grasshoppers came in great dark clouds that settled on the landscape like a writhing blanket. Cutworms, wireworms, and grass fires followed. The Havre Plaindealer called the catastrophe “the worst in the history of the state.”

By the following spring, the drought spread over all of eastern and central Montana, where temperatures hovered between 100 and 110 degrees. Hot, brutal winds blew the soil the homesteaders so laboriously plowed. Ominous brown-grey clouds rolled across the vast horizon, denuding 2,000,000 acres and partially destroying millions more. By the fall of 1918—just as the War in Europe was coming to an end—the haunting face of depression appeared everywhere. And there was no end in sight.

Lacking food, seed, land, and savings, and with little or no help from state relief agencies, the homesteader left Montana even more quickly than he came. The exodus started in the fall of 1917 and by 1919, when the post-war drop in wheat prices created an even more impossible situation, they left in droves—one with a poetic sign on his wagon: “Twenty miles from water, forty miles from wood. We’re leaving old Montana, and we’re leaving for good.” An estimated 60,000 people left Montana during the 1920s, many of them moving to Washington, Oregon, and especially California. Other would likely have followed, but they simply didn’t possess the means. Montana was the only state that lost population during the “roaring” 1920s.

The extent of the disaster was staggering and grim statistics tell the story. Between 1919 and 1925, roughly two million acres passed out of production and 11,000 farms—about 20 percent of the state’s total—were vacated. Farmland prices fell by 50 percent, 20,000 mortgages were foreclosed, and half of Montana’s farmers lost their land.

A generation of reckless lending practices also wrought havoc on the state’s financial institutions. Between 1920 and 1926, more than half of Montana’s commercial banks failed. Of these, 214 closed their doors, never to reopen again. Montana’s bankruptcy rate became the highest in the United States.

The collapse of the Montana homestead movement marked the end of the frontier era in the Treasure State. An era of pronounced economic growth and unrivaled optimism was replaced by an unparalleled time of economic stagnation and tragic loss. The terrible 1920s were followed, of course, by the Great Depression of the 1930s, and Montana’s painful ordeal only continued when the rest of the nation’s economic rollercoaster plummeted headlong into its greatest economic crisis.

If Montana’s history has been shaped by one telltale pattern, it is the cycle of boom-bust development so clearly embodied in our homesteading and mining experiences. It is the thing, more than any other, that has shaped our character and cultivated our resiliency. Without hope and hardship, we simply would not be.

~ Derek Strahn, historic preservation consultant and writer, teaches history at Bozeman High School. He was the principal historian on the recently approved Butte-Anaconda National Historic Landmark District nomination. He can be reached at [email protected].

Leave a Comment Here