The Ozark Club

Comedy, Burlesque and All that Jazz!

There was just something about the Ozark Club. For three decades from 1933 to 1962, this African American-owned nightclub evolved from a “colored club” into an entertainment sensation in a most improbable place—Great Falls, Montana. Nestled in the heart of the vibrant working class lower Southside, on the edge of the railroad district, the Ozark Club on Third Street South was surrounded by seedy bars, cafes, hotels, and houses of ill repute.

From its founding in 1884, Great Falls practiced a “soft” form of segregation, with African American residents restricted to the lower Southside. Over the years this segregation became more rigid, with blacks excluded from union membership, jobs at the copper smelter and rail repair yards, barbershops, nightclubs, and restaurants. Blacks worked downtown in service industries or for the Great Northern Railroad, worshiped at the Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (A. M. E.) Church, lived in black hotels, the porters’ quarters of a few family homes, and sought entertainment at “colored clubs.”

After 13 long years the failed Prohibition experiment ended on December 5, 1933, and Montana became “wet,” serving alcoholic drinks. That night young Leo LaMar opened a new colored club, the Ozark Club, in a small house on Fourth Alley South. The Ozark was an immediate success, and by the fall of 1935, the Ozark Club moved to 116-118 Third Street South on the upper floor of a large wood-framed building. Downstairs was the popular Alabama Chicken Shack Restaurant.

Owned by dynamic Leo LaMar, the Ozark Club anchored black nightlife in Great Falls during the 1930s. The outbreak of World War II, brought hundreds of white and black soldiers to Great Falls to operate two Army air bases. The Ozark achieved fame for its quality entertainment featuring some of the best jazz musicians in the western United States.

According to his daughter, Sugar, Leo LaMar was born in Chicago in 1902, the son of an African American mother and a Chinese father. The Great Northern Railroad brought young Leo LaMar west to Great Falls in 1920, and for many years he worked as a dining car waiter on the Havre to Butte line. Within weeks of his arrival in Great Falls, Leo began boxing as “Kid Leo,” and he fought an early bout as a lightweight in 1921, defeating “Rough” Reed, a heavier white boxer in two rounds. Sports writers reported that ‘Kid’ Leo “took the ‘Rough’ out of ‘Rough’ Reed” and called him “one of the cleverest youngsters who ever appeared here.” Over the next five years, Kid Leo fought other bouts winning most of them. His fighting name and reputation stayed with him over the years.

From its opening in 1933, the Ozark Club was known for its fun and music. Initially catering to a black clientele, early in World War II Leo LaMar successfully broadened its base to a multiracial crowd under the theme, “All are welcome.” Segregated Great Falls during wartime was a city ready for an interracial nightclub where all were welcome. There never was a dull moment at the Ozark Club.

Within the black community, the Ozark Club and Leo LaMar vied for leadership with the long-established Union Bethel A. M. E. Church through civic activities as head of the local NAACP and sponsor of a black Boy Scout Troop. Leo cultivated the chief of police and other leaders in the white community by operating the lively nightclub that was emerging as the jazz capital of Montana.

LaMar’s strategy for the Ozark Club’s success rested on an exceptional entertainment package anchored by a talented house band. The key element became tenor saxman Bob Mabane, who came up through Kansas City early in the be-bop jazz era. Mabane joined the Jay McShann band in 1940 as McShann was achieving national fame. Mabane sat side-by-side with young Charlie “Bird” Parker until the band disbanded in 1942. In 1948, Bob Mabane arrived in Great Falls to lead the Ozark house band, the Ozark Boys. Mabane remained in Great Falls leading and playing sax until the O-Club closed in 1962.

Ozark Club entertainment included the Ozark Boys, vocalists, exotic dancers, and comedians. Black celebrities, sports figures, and traveling bands knew they were welcome. Sergeant Joe Louis visited the Club in 1945. Pop Gates and the Harlem Globetrotters spent their off-court hours at the Ozark during their annual visits to Great Falls. Teenage June Elliott, whose mother prepared snacks at the club, remembers the night Leo LaMar arranged with the Chief of Police for Lionel Hampton and his band to spend all night playing at the Ozark with the doors locked and the music continuing until morning light.

The Ozark’s traveling musicians, singers, and exotic dancers were often on the Great Northern “chitlin’ circuit” out of Detroit. Some of these entertainers were on their way up and would later achieve fame. Top musicians Oscar Dennard, Stan Turrentine, and many others played with the band. Young Red Foxx practiced his early comic routines. Infamous striptease artist, Miss Wiggles, “the Wiggleinest woman in the West,” brought down the house with her contortions in dancing upside down on a chair stripped to pasties and g-string.

During the 1950s the Ozark Club was flying high and attracting an interracial crowd of patrons that included servicemen, couples and singles, traveling salesmen, and visitors out for a good time. Patrons climbed a narrow, dark staircase leading upstairs to the club. There in a dim and smoky room, Leo held court, a fixture at the bar on one end, and the band at the other end. Leader Bob Mabane attracted the musical talent to keep the Ozark Boys one of the finest small dance bands west of the Mississippi. Gambling quietly went on in a back room. Leo’s wife, Bea, ran her “gravy train” prostitution ring at the nearby LaMar Hotel. Leo LaMar was a power in the Great Falls community.

But by 1957 dark clouds began to form. That year newspaper headlines broke revealing sordid details of the LaMar Hotel operations. Leo, Jr.’s spectacular death with four friends in an early morning car-truck crash in June 1961 was a devastating blow to his father. Leo LaMar’s heart attack and death one year later in June 1962 marked the end of an era, and the impending demise of the Ozark Club. Three weeks later, a late night fire forced emergency evacuation of about 50 staff and patrons, as the Ozark Club burned to the ground. Rumors swirled that the fire was not accidental.

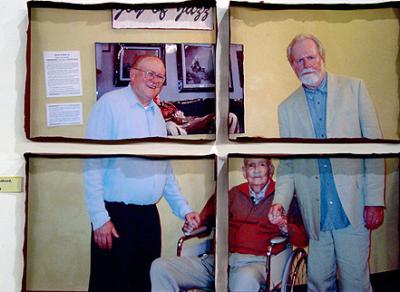

Leo LaMar was gone, his famed Ozark Club was gone, but this was not the end of the story. Fortunately for posterity, insight into the Ozark Club and its hot jazz survived. During April-May 2005 in a series of interviews at Fireside Books, Philip Aaberg, Montana’s modern musical treasure, and this author jointly interviewed Jack Mahood, then 86 years of age. Jack reminisced about the early days of jazz music in Great Falls, including the Ozark Club, where as a young white musician he jammed on Sunday afternoons.

During our first session, Jack Mahood casually mentioned that he had discs that were recorded at the Ozark about 1950 when he jammed with the Ozark Boys. Several days later Jack brought the recordings. What a rare historical treat it was to listen to “Sweet Georgia Brown,” “Lady Be Good,” and other jazz while Jack painted a word portrait of the Ozark Club, the musicians, and the musical life in Great Falls in the late 1940s and 1950s. Phil Aaberg captured the moment: “Jack put the first disc on and dropped the needle. It was ‘Royal Roost,’ a tune named after a nightclub made famous by a Charlie Parker record. Honestly, the hair on the back of my neck stood straight up.”

Armed with Jack’s recordings and my research into the Ozark and the black community, Phil Aaberg worked with Director Chris Morris to bring the Ozark Club back to life at The History Museum. I worked with the Tribune to bring out the colorful history of Leo LaMar and the Ozark Club. Karen Ogden’s Ozark story sparked the greatest response ever to a Tribune article with stories pouring in from Alaska to Washington, D. C. Leo LaMar’s daughters, Sugar and Bunny LaMar, came from Los Angeles bringing dozens of photographs to help tell the story. The night of June 7, 2007, The Ozark Club in Great Falls, Montana, came back to life with “A Night At the Ozark” playing to a packed house and an electric environment. And on September 10, 2011, the History Museum and Phil Aaberg hosted Tommy Sancton and the New Orleans Legacy Jazz Bank.

The Ozark flame was re-ignited.

~ Ken Robison is historian for the Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton and the Great Falls/Cascade County Historic Preservation Commission. Robison has written two books, Fort Benton and Cascade County and Great Falls. The Montana Historical Society named him one of two Montana Heritage Keepers for 2010, and The History Museum presented him an Historic Legacy Award in 2011. Ken is a retired Navy Captain, after a career in Naval Intelligence.

Leave a Comment Here