Who the Hell Was Montana Frank?

A Wild West Show Mystery

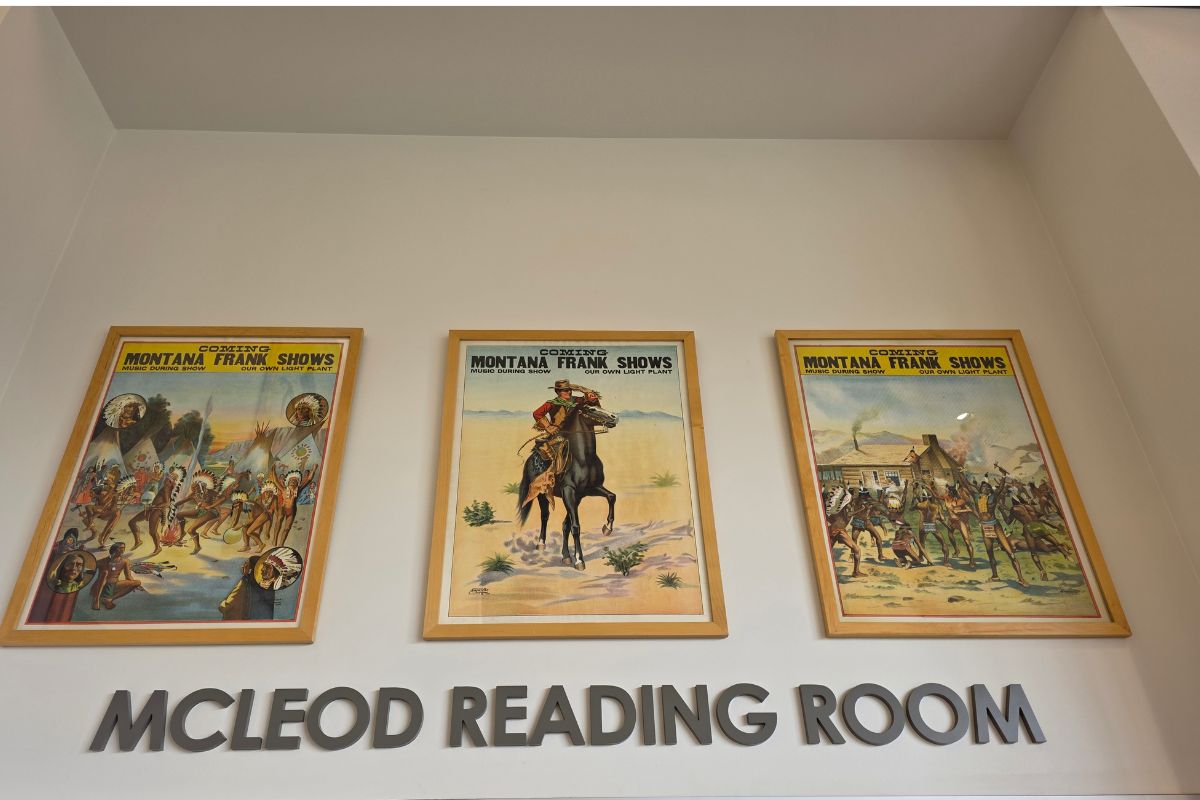

The first time I saw posters for his Wild West show, tucked away in the Montana Room of the Bozeman Public Library, I wondered, "Who the hell is Montana Frank?"

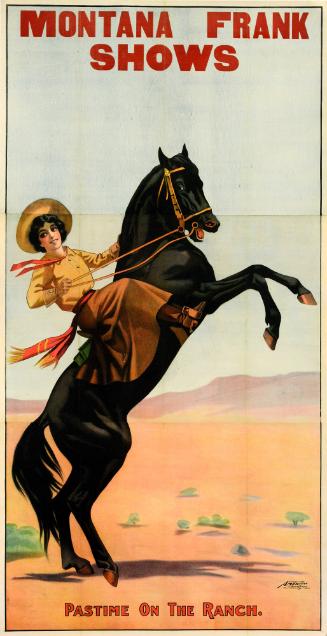

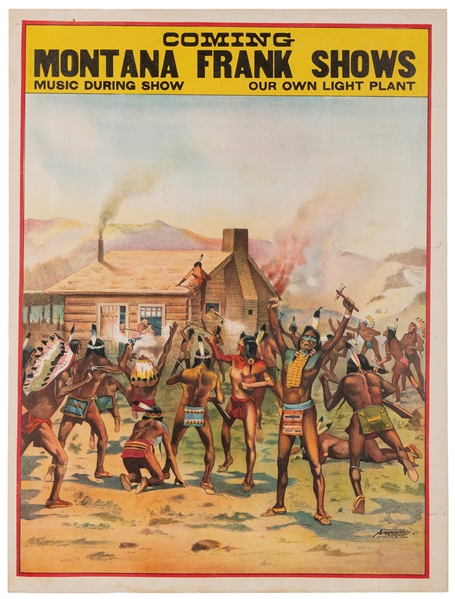

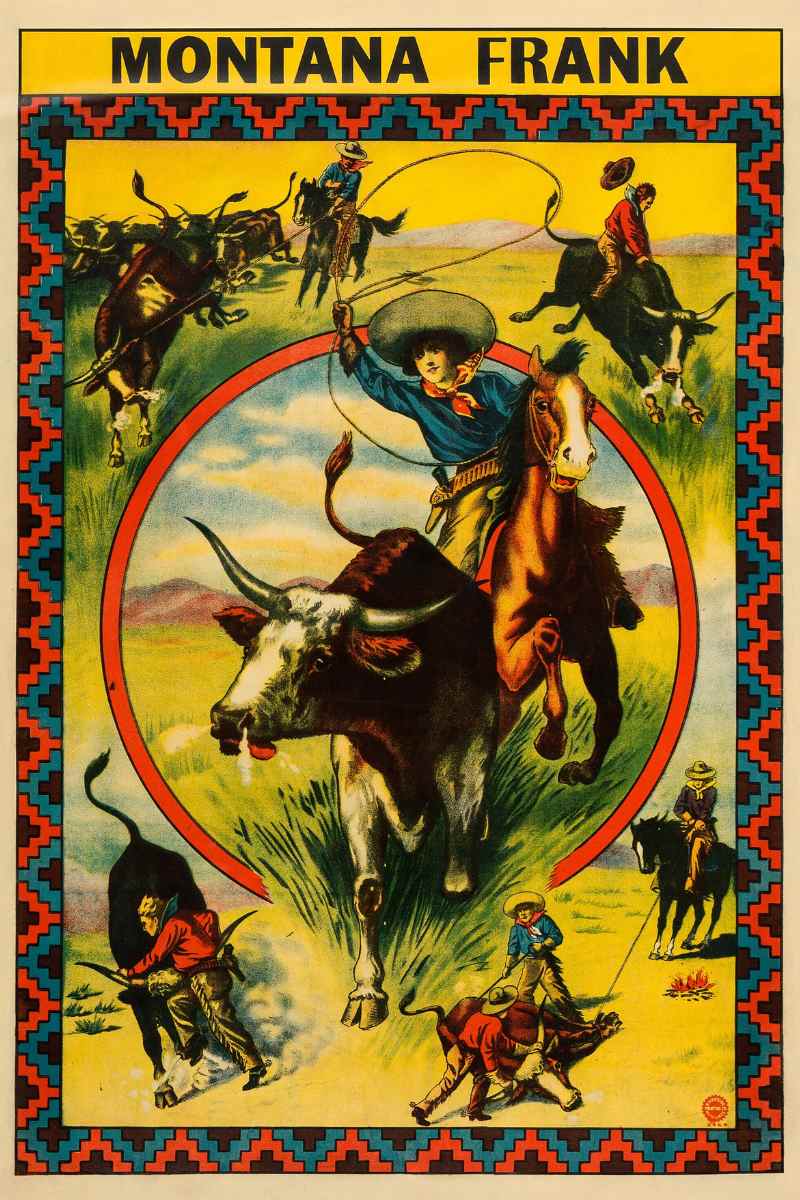

The images revealed little. Only the words "Montana Frank's Shows," or "Montana Frank's Wild West" and Nor was Montana Frank pictured on the posters. There were comely cowgirls, covered wagons, Indians, even a cowboy or two. But there are no dates on the show posters. No cities. No inkling of where on the vast continent of North America someone might have been able to see Montana Frank. Nor was Montana Frank pictured on the posters. Only scenes sufficiently lacking in specificity to stand for almost anything broadly "Western."

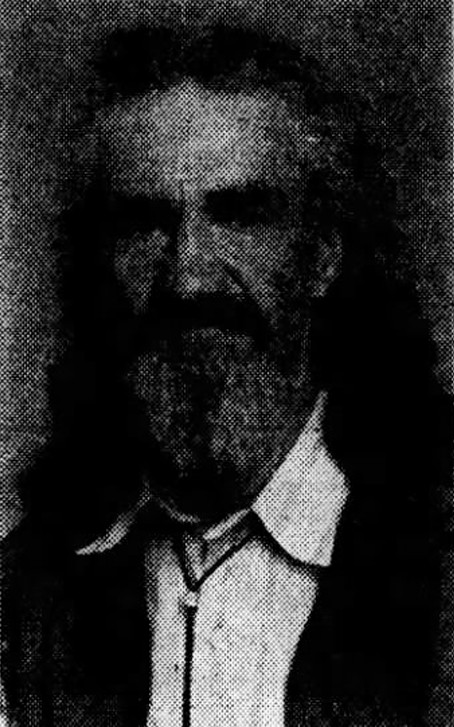

So I began searching for him, curious. Eventually I succeeded in finding two or three photographs of the man, all taken in the late 1930s when he was an older man. As the world inched toward a second World War, Montana Frank launched a last effort at fame, appearing in a series of interviews and curiosity pieces in Idaho newspapers. In both, he wears an instantly recognizable Western goatee and long white hair. He resembles someone out of central casting for the oaters of the day. As a matter of fact, he looked just a little like Buffalo Bill.

The Helena Daily Independent reported on April 11, 1938, that "Montana Frank McCray, Last of Buffalo Bill Scouts, Is Found Living in Salmon River Wilds."

The article describes its subject.

"He is Frank McCray, 73, better known to pioneers as Montana Frank, a true frontiersman who is said to be among the last of the Buffalo Bill scouts and rough rider. He was associated with Buffalo Bill as a scout and a hunter for a number of years and helped to make history in the days when Montana was still a frontier... His life for many years was intimately entwined with the growth and development of Montana."

He was born in Butte in 1864, the article says. By Frank's own reckoning, that made him the "second white child" born in the town. Elsewhere, and more often, he would make the claim that he was indeed the first white child born there. His father, he said, would later become a major and the commanding officer at Fort Shaw, where he would meet his demise at the hands of Indians. Frank said that he, too, bore the scars of many a tomahawk. He also rode through the Lolo Pass to "gather horses and mules for the government" and was mustered by Fort Shaw to provide game for those who lived there.

In 1937, the Idaho Statesman ran a contest for the best article written by a newspaper delivery boy. The winner was Arther Troutner, route 43, who interviewed Montana Frank and reported that he was not just the first or second white child born in Butte, but the first white child born in the whole state. He is also described as a member of seven Indian tribes, including the Blackfoot, although a Blackfoot brave was the one responsible for at least one of his scars. It says that he was also a miner, plying that trade in Africa for six years. He was also, naturally, a friend of Charlie Russell and Buffalo Bill Cody. He had known the latter since the 1880s and had performed with his Wild West show at the Chicago World's Fair, Madison Square Gardens, and on two tours of Europe. He also had, ominously, ten notches on his pistol.

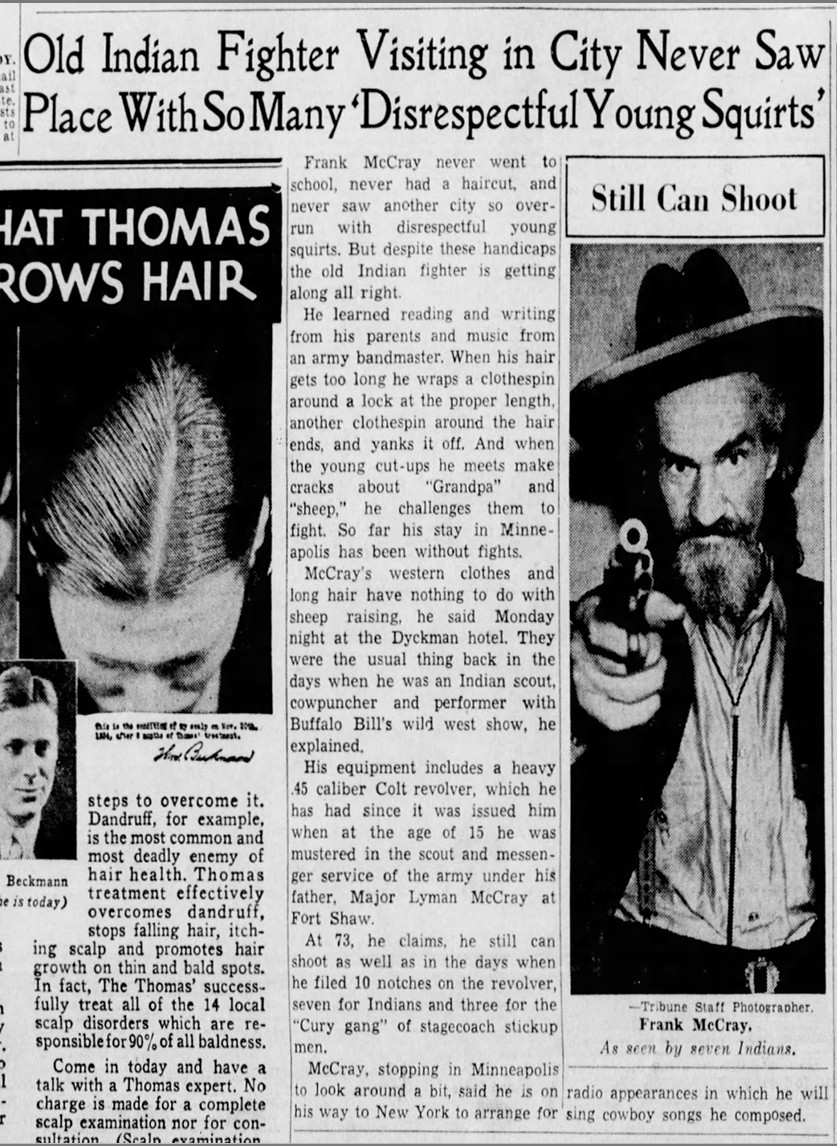

Now, the article reported, the septuagenarian kept to his ranch at the foot of the Lemhi Trail on the Salmon River. That is, except for when he was composing "songs and melodies of the Old West" or on tour performing them at radio stations back east, like Minneapolis's WCCO, WTCN, and KSTP. While in Minneapolis, incidentally, he reported to a local reporter that he had never seen a town so full of "disrespectful young squirts" who made fun of his hair, which he claimed never to have had cut in his life. Instead, he simply tore it out: "when his hair gets too long he wraps a clothespin around a lock at the proper length, another clothespin around the hair ends, and yanks it off." Montana Frank supposedly responded to the mockery hurled by the squirts of Minneapolis by challenging them to a fight. So far, the article said, no one had taken him up on it.

Another human interest piece from the Spokane Spokesman-Review McCray revealed that he had been writing a song on the subject of the personal life of the recently abdicated King Edward VIII:

"Prince of Wales of England,/ Crowned Edward Eighth One Day,/ Fell in love with an American girl/ and gave his heart away."

"King Edward has done no wrong," he concludes in the final verse of the song. After all, he had said in another interview, he was "personally acquainted with England's ex-king and admires him with a warm sincerity."

If Montana Frank's exaggerated claims were exaggerated, hell, wildly exaggerated, who could blame him? In the early days of the American experiment there was a hunger for legends, for a mythology of our own. There was also, concomitant to that urge, a great number of folks who were looking to become legends through any means necessary. Outlaws chose violence. Others, like Buffalo Bill, chose to put on a show.

Some legends are born, and some are made. Some are forced into being by marketing, publicity, and advertising. If Montana Frank never quite became a legend, it wasn't for lack of trying.

THE WILD WEST SHOW: FROM BUFFALO BILL TO BUCKSKIN BEN

Buffalo Bill opened his Wild West for the first time in 1883, and some twelve years later Frederick Jackson Turner famously declared the American frontier closed.

Speaking at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, Turner held that the frontier was central to and essential for the American spirit - something to conquer, and be conquered by. By then, however, the frontier had gone from a curtain that descended across the continent to a patchwork of shrinking parcels of wilderness that would, all too soon, give way to settlements and, ultimately, to civilization. Civilization was at once the end-goal and the boogeyman haunting America. Huckleberry Finn, when faced with the prospect of civilization, preferred to "light out for the territories." Many others felt the same way, but lacked the hardy constitution. They might have to settle for a stack of dime novels or a Wild West show like Buffalo Bill's, or Montana Frank's, if one happened to be traveling through, and in so doing they could, hopefully, capture at least a little of the enchantment and adventure.

As you can imagine, the experience of seeing a Wild West show could vary a great deal depending on the size of the show, your location, what year it was, whether you were a crowned head of Europe, etc. The biggest were beyond huge, like Buffalo Bill's performance at Chicago at the World's Fair in 1893. There, he put on 318 performances with an average of 16,000 people every time. That's roughly 5.1 million people. Of course, we have to consider that some of those people must have come back to see it again, perhaps over and over.

That's a far cry from the smallest Wild West show on record, which pitched its meager tent on the lawn of the courthouse in Terre Haute, Indiana. It consisted of Buckskin Ben, his horse, and his wife, who sold tickets and served as the drum player. This anecdote comes from Chief William Red Fox, a former Buffalo Bill Wild West alum who witnessed the miniature production as it was hastily put together, performed, and taken down. He said that Buckskin Ben's wife "never skipped a beat."

If someone, Montana Frank perhaps, had a much smaller-scale show than Buffalo Bill's Wild West, they would have to resort to posters with generic images selected from printshops offering catalogs full of off-the-shelf, non-specific Western scenes that could be ordered with a bit of text on top to advertise smaller shows unable to afford their own artists. These images offered up generic copies of the bigger shows' spectacles and feats, with comely young lady shootists, Indians raiding a traveling stagecoach, etc. Montana Frank's posters were printed by the American Show Print Co. of Milwaukee, sometime between 1909 and 1911, and presumably were purchased not long thereafter.

To follow his trail, I began by scouring newspapers.com for mentions of Montana Frank. As the number of clippings grew, so did a list of some of the performers with whom he shared the stage: Fresno Rose, the Circle M Rangers, Cattle Annie, and others. It became clear that he was less a Wild West show proprietor than a vaudeville performer on the Canadian and Midwest circuits who borrowed the imagery of the Wild West show for what he occasionally dubbed his "miniature rodeo."

The earliest mention of Montana Frank that I could find in the press was an announcement that he would be appearing live along with Hadji the Horse With a Human Brain and a pack of trained dogs — literally a dog and pony show — before 30 minutes of silent films in a Fort Wayne, Indiana theater. He stayed there for some months, performing weekly. The Fort Wayne Journal Gazette wrote that "Montana Frank with his cowboy fun" would demonstrate "the life of cowboy pastime on the plains," and described his lonesome hours out West "spinning his lariat." It mentions the presence of his pony (not, alas, Hadji the Horse With a Human Brain) and mentions a demonstration of lasso tricks.

I next found him in 1916, touring with a five-reel motion picture of the Miles City Round-Up, telling audiences he was from Miles City, something he didn't mention as much in his later years. He took his film to Waukesha, Wisconsin, as well as Oakland and Moscow, Minnesota. At Redwood Falls, Minnesota, he found that the local theater space didn't have a projector, and was unable to mount his show. He did, however, buy a car; the local paper likened it to a bucking "broncho," with which he was, of course, well acquainted. One wonders what happened to his little pony.

The next year he popped up in Wisconsin in June. In communities such as Neenah, Osh Kosh and Fox Lake, he continued to project his film and, most probably, perform rope tricks while providing his own colorful commentary.

He continued with his film, which must have been getting a bit out of date if he wasn't updating it every year, until at least 1921, when the Windsor Star in Ontario mentions that his Miles City Round-Up was able to draw a big crowd.

In the early to mid-1920s, he seems to have abandoned the film for more standard Wild West fare. The Camden, NJ Courier Post records that, for the American Legion Winter Circus of 1924, his show "was an added feature. The cowboys raced their horses around the arena 'shooting up' the armory."

After which I was unable to find Frank anywhere for nearly six years. An interview and an obituary claim that he was engaged in silver mining in Mexico and/or mining in Africa. He also said he had two daughters from his first marriage who were now living in Mexico with their husbands. Does his absence from the press in this period represent a furlough from entertainment? If so, it was only temporary.

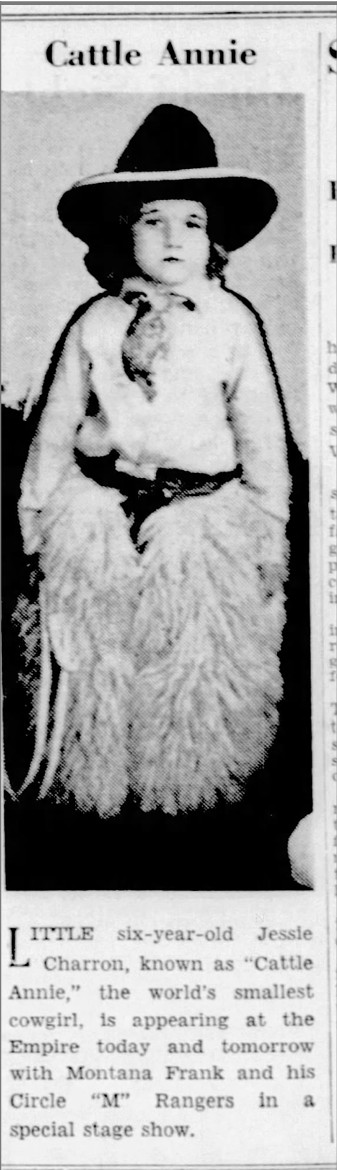

In 1933, Frank performed at Toronto in August and was injured by a horse in Ottawa two months later. Two engagements in 1934 took place in North Bay, Ontario and in Vancouver. In 1935, Montana Frank's Canadian performances continued at Sault St. Marie where he appeared as part of Con's Greater All Canadian Shows with 'Cattle Annie — the 5 year old cow girl' and 'Rumba's Musical Review.' That same year, back in the States, his Wild West act appeared in Manitowoc, Wisconsin as part of a Wild West Show "Pic-Nic" that included music by the Denmark Orchestra, ice cream, and free exhibitions by Montana Frank.

In 1937, the Windsor Star in Ontario, alongside notices for Greta Garbo and Lionel Barrymore movies, advertised "Montana Frank and His Circle M Rangers," along with "Ropin' - Singing - Sharpshooting," and "Whip-Cracking," not to mention autographed photos of the "'World's Smallest Cowgirl." Cattle Annie, incidentally, told a reporter, "Well, when I grow up I'm going to get married, and if he ain't any good, I'm going to get a divorce!"

That same year, Montana Frank presided over a meeting of the "Amalgamated and Enthusiastic Association of Drug Store Cowboys" in Lewiston, Idaho, according to the Spokane Spokesman-Review. A month later, the Idaho Statesman of Boise reported that the 73-year-old McCray "entertained the patients at the Veteran's Facility...by recounting some of his early experiences as an Indian scout. He also sang several songs."

That same year, Montana Frank presided over a meeting of the "Amalgamated and Enthusiastic Association of Drug Store Cowboys" in Lewiston, Idaho, according to the Spokane Spokesman-Review. A month later, the Idaho Statesman of Boise reported that the 73-year-old McCray "entertained the patients at the Veteran's Facility...by recounting some of his early experiences as an Indian scout. He also sang several songs."

At many of his Canadian engagements he was accompanied by someone billed as Fresno Rose, his wife who he is described as having married when she was 14 years old. Fresno Rose is supposed to be from Texas, yet curiously she never appeared in any of Montana Frank's American shows during the 1930s. Cattle Annie, sometimes named as Jessie Charron (or Sharon) in one newspaper, is several times billed as their daughter.

Whoever Cattle Annie was, she may have been the daughter of "Fresno Rose" — or not, given that she is elsewhere identified as one Jessie Charron, or Sharon — but she was almost certainly not the daughter of Frank and his actual second wife, Grace. They married in September of 1936, when she was 47 and he was nearly 72.

But then, vexingly, there is one mention of a public appearance, as late as 1947, of Montana Frank with Fresno Rose in Detroit, when he would have been 83 years old. This is very nearly the latest mention of Montana Frank I could find, ten years after his interviews in Spokane and Idaho newspapers. He would have been old, but perhaps not too old to tell a story or two, or maybe even do a shooting trick, with help from his assistant. Of course, by that time maybe the greatest trick he could pull off was to stand there, look the part, and be a creditable representation of an actual Old West figure well past his prime.

TRUTH, LIES, AND LARIATS

His final bid for fame, before his obituary got him a little ink for the last time, was a letter written to the Madisonian in Virginia City when he was 90 years old. He reiterates again the greatest hits of his career — he was a Pony Express rider, a rider and roper with Buffalo Bill who accompanied him to the World's Fair, and to Europe. He had acted as a courier from Sheridan, Wyoming, all the way to Missoula, Montana. He left out mention of tomahawk wounds, notches in gun barrels, and songs written for errant royals. He claimed, finally, to have never learned how to read and write, despite having told the Minneapolis Star Tribune years earlier that he had learned both at the feet of his parents, not to mention his apparently having written the letter in question.

The problem of the nature of truth regarding Montana Frank is compounded by the certainty that, whoever he was, he was almost certainly stretching the truth for the benefit of his stage persona, which is to say, he lied.

Could he have been a Pony Express rider, as he repeatedly claimed over his life? Probably not, considering that short-lived operation had folded before he was born.

Apparently, we must also be skeptical of his claim to have performed with Buffalo Bill's Wild West during 1893 and the years immediately following. I wrote to the archivists at the Buffalo Bill Cody Center of the West, and one of them was kind enough to reply that Montana Frank couldn't have been a trick roper during those days because all of Buffalo Bill's ropers were Mexican at that time. Could he have been employed in some other capacity?

Was his father really one of the vigilantes who helped to hang George Ives in Virginia City, as he claimed late in life? Possibly, but that requires his father to then relocate to the barely-there gold mining camp of Butte in 1864 a year later. Then, when McCray was 17, his father was killed by an Indian attack on Fort Shaw. As far as I can tell, no such attack occurred in 1881. At any rate, there doesn't seem to be a Major Lyman McCray listed as commanding officer of the camp.

As for having been close personal friends with C.M. Russell, or his having met Edward VIII, the one-time heir to the throne of England? You decide.

Or consider the supposed 10 notches on his pistol — seven for Indians, three for members of the Curry Gang. In his letter to the Madisonian, he mentions being a mail courier through the Hole in the Wall. But Curry's gang was most active in the late 1890s, so was McCray somehow shooting outlaws after his supposed stint with Buffalo Bill's Wild West?

It's all frustratingly murky — not impossible, but difficult to prove either way. Could Frank McCray have really been who he says he was after all? Is there any truth to any of it?

FRANK'S LAST ROUND-UP

In the end, who the hell was Montana Frank anyway?

It is impossible, for me, anyway, not to read Montana Frank as in some ways the inverse of Buffalo Bill. If the flood of Buffalo Bill's imitators, like Young Buffalo, Pawnee Bill, Buckskin Ben, Texas Jack, and the rest, in turn, reveal something like a portrait of Buffalo Bill himself, then what does a portrait of Buffalo Bill reveal about Montana Frank?

Bill Cody had great success riding a big express train along the line between fact and fiction, between fantasy land and the "real" world of everyday life. It made him a legend, but it also made him a bit blurry. Somewhere in his past were genuine accomplishments, but layers and layers of mythmaking and storytelling had obscured the edges of what was real. By the end, even Cody wasn't sure what he had really done. On the subject of Yellow Hair, sometimes known as Yellow Hand, whom Bill had famously killed and scalped in the weeks after the Little Big Horn, shouting "First scalp for Custer, boys!" he would later say, "Bunk! Pure bunk! For all I know Yellow Hand died of old age."

Montana Frank seems to have seen Cody's success and tried to emulate it. However, he had a different ratio of truth to fiction in the makeup of his stage persona. There had to be because not all of us are as blessed with the life of adventure and derring-do that made Buffalo Bill famous in the first place: the core, you might say, around which Cody so successfully built his legend. Not all of us, as Montana Frank probably knew, get to be Indian scouts, to shoot up the Curry Gang while on a daring mission through their territory.

At 90 years old, Montana Frank was still writing to the newspaper to tell people that he was probably the last living American Western legend. He was unlikely to make any money from the letter, so why did he write it? For recognition? For fame? Recognition, fame, and financial incentive go hand in hand for a working vaudeville performer, but what value are a few eyes reading your name in a Virginia City newspaper to a nonagenarian living in the woods?

And yet, this odd letter and its spurious claim that he couldn't read or write, that he was an important part of the state's living history, that he had in fact lived a Western adventure (and not, pointedly, the life of a Midwestern vaudeville performer of modest success) make him seem more fragile, more human to me.

His lies, perhaps, were not so much unforgivable sins as features of his stage persona. But as he achieved the impressive feat of reaching nearly a century old, it seems to have been a little more fame, just a helping more of the admiration of the crowd that he craved.

When he died in 1959, newspapers all over the country devoted a small column or two to printing his wild stories without question. No one wants to doubt an old man.

I think that Montana Frank realized at some point that the problem, his enemy, was the truth. He would have to conquer it, and as long as he fought at it hard enough, and long enough, he would eventually defeat it. Unseat it. Dethrone it. He therefore entered into a tenuous partnership with his audience. He would lie to them in an entertaining and outrageous way. They, in turn, would at least pretend to believe his tales.

Buffalo Bill had worked out a similar scheme with his audience when they praised the "realism" and "authenticity" of his show. "Authenticity," whatever that means, is a rare commodity, sought after but scarce, while the appearance of authenticity is a lot easier to scrounge up and sell. Just ask John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, or Yellowstone's creator, Taylor Sheridan. It might just be that the Western, a two-dimensional variant of the Wild West show, thrives on exactly the same primordial ooze as did Montana Frank and, for that matter, Buffalo Bill.

In March of 1959, there were no more Indian wars, no buffalo herds, and no vaudeville. But Sputnik III did circle the earth, beeping, and it was the same year that Xerox introduced the commercial copier and the Boeing 707 jetliner began flying passengers from New York to Los Angeles. In that year which seemed so near the future, the Spokane Chronicle posted a small piece about Montana Frank McCray's passing.

They wrote that McCray "did the things that were so real then — some plain hard work — and which now sound so romantic... He touched enough of the early-west high spots to have served, had he been asked, as a one-man reference library for a whole studio of script writers."

"And still," the writer concludes, "he wasn't what you'd call famous."

Leave a Comment Here