Rosebud Battlefield State Park: "Where the Girl Saved Her Brother"

THE BATTLE OF THE ROSEBUD, which occurred on June 17, 1876, is commonly perceived as merely a prelude to the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Interest in the Rosebud fight certainly does not match the last-stand mystique that historically surrounded the demise of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and Seventh Cavalry troops under his immediate command at the Greasy Grass. However, Paul Hedren (2019) astutely observes, in the definitive work on this engagement, that "no Indian wars battlefield in America is [as topographically] diverse and expansive as Rosebud Creek, Montana."

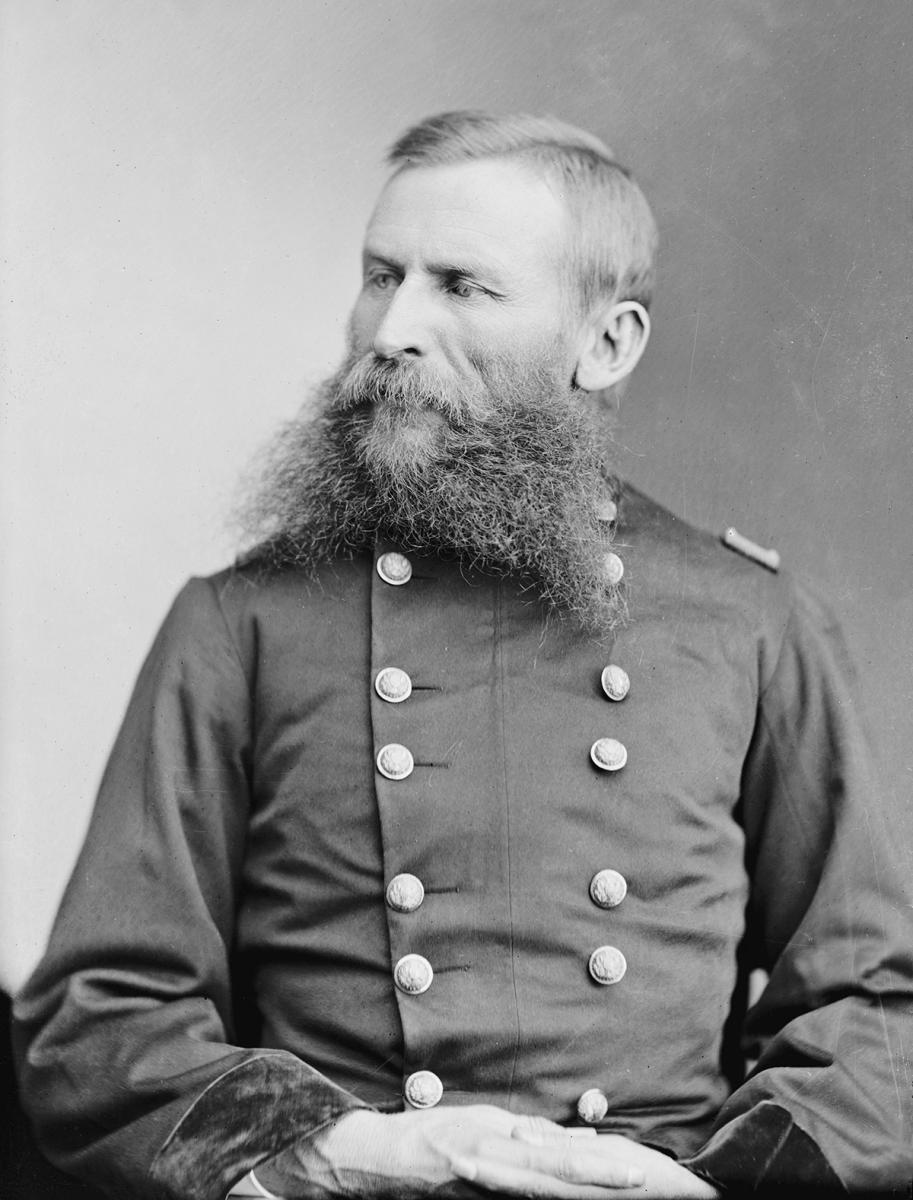

It is also distinctly possible that the Rosebud fight was the largest pitched battle ever fought between the U. S. Army and Plains tribes. The Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition, commanded by Brigadier General George Crook, numbered some 1,300 men, which included 15 companies of cavalry, five companies of mounted infantry, and an auxiliary force of 176 Crow and 86 Shoshone warriors.

Estimates of Lakota and Northern Cheyenne combatants are derived from statistical extrapolations. Historians have painstakingly chronicled the aggregation of villages involved in the Rosebud fight. Based on ratios for persons and warriors per lodge, calculated from demographic data compiled by Harry Anderson (1960), John Gray (1976) and Robert Marshall (1984), Hedren concludes that the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne probably fielded "[s]omewhere between 750 to 800" warriors. Those figures comport well with Gray's earlier projection of "850 fighting men."

On the other hand, casualties from this engagement appear to have been surprisingly low. According to Gray, "A survey of ten sources provides the names of nine soldiers killed and 23 wounded," numbers that correspond closely with Crook's official report, which documents 10 fatalities and 21 wounded in action. However, Crook's most respected scout, Frank Grouard, cited "twenty-eight soldiers killed and fifty-six wounded."

Cheyenne and Lakota losses are less clear. Crook carefully qualified his remarks on this point, stating only that the remains of 13 enemy warriors were left "in close proximity to our lines." According to some Cheyenne informants, 20 or more Sioux were killed at the Rosebud. Other sources advanced much higher, but more speculative, totals for Lakota casualties.

History may have told a much bloodier tale if the opening salvos of conflict had unfolded differently. When gunfire was first reported around 8:30 A.M., Crook's column was bivouacked along the Rosebud. Soon thereafter, scouts returned from their reconnaissance patrols at a gallop, with a large party of enemy warriors in hot pursuit. Crow and Shoshone auxiliaries were the first to engage their Lakota adversaries. For 20 minutes, Kingsley Bray emphasizes, the battle "teetered in the balance." According to Grouard, who was then with Crook, "if it had not been for the Crows, the Sioux would have killed half of our command before the soldiers were in a position to meet the attack."

Viewed in its entirety, Hedren describes Rosebud as a "baffling engagement," one marked most fundamentally by "concurrent action across an expansive field," wherein massed warriors took full advantage of the area's rolling topography to seemingly appear and disappear instantaneously at disparate points on the battlefield. Those factors contributed to grossly exaggerated estimates of enemy combatants, ones advanced in the battle's immediate aftermath and later publications, by Army officers and embedded newspaper columnists.

By contrast, there is no question that combat in the "Gap" and Kollmar Creek sectors factored disproportionately in the historical record and outcome of Rosebud. Kollmar Creek, an insignificant and typically dry watercourse, transects the western portion of the battlefield. On that fateful day, it earned a host of ominous nicknames, the most foreboding of which was conferred by Captain Guy Henry, who was grievously wounded there. Henry appropriately characterized the area as the "Valley of the Shadow of Death."

Some 210 members of the Third Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William Royall, navigated a torturous, 700-yard gauntlet from their initial position on Kollmar's southern crest to Kollmar Crossing. Their retreat, which met with progressively increased resistance, culminated in the fiercest fighting of the entire engagement. This portion of the battlefield was also the one area in which the Lakota possessed a decided numerical advantage.

With every fourth soldier sequestered as a horse holder, Royall's four companies could muster a skirmish line that included no more than 170 troops. By the time they approached Kollmar Crossing, Royall's command faced a hornet's nest of highly motivated warriors, one that Lieutenant James Foster of Company I estimated at "five to seven hundred Indians."

Regimental officers who were also Civil War veterans agreed that "they never in their experience saw anything hotter" than the ferocious firefight that erupted at Kollmar Creek. Outnumbered and temporarily isolated, the Third Cavalry incurred all of the nine fatalities, as well as 16 of 21 wounded soldiers, listed in Army reports. Company L, led by Captain Peter Vroom, paid the highest price, suffering five fatalities and three wounded in close-quarters, often hand-to-hand, combat.

Medals of Honor were awarded to first sergeants Michael A. McGann of Company F, Joseph Robinson of Company D, and John Henry Shingle of Company I for gallantry exhibited at Kollmar Crossing. Elmer Alonson Snow, the 24-year-old bugler of Company M, also received a Medal of Honor for his harrowing ride, while severely wounded, across the Gap.

A topographic feature that is clearly visible due north of the park's entrance, the "Gap" is flanked by highlands to its east and west. This wide notch forms a natural corridor through which Lakota and Cheyenne forces launched their initial assault on Crook's column. High ground adjacent to this area was fiercely contested throughout various portions of the engagement, but the Gap itself was subsequently traversed only by the bravest of the brave. Therein, a handful of warriors conducted "bravery runs," a quintessential expression of the Plains Indian warrior tradition.

Such men rode across open ground, often repeatedly, for the express purpose of drawing heavily concentrated fire upon themselves. Those actions provided incontrovertible evidence of the rider's courage and, arguably, the strength of his war medicine. Crazy Horse, the great mystic warrior of the Oglalas, was particularly renowned for this practice.

Baptiste ("Big Bat") Pourier, a respected guide and interpreter, witnessed one of Crazy Horse's bravery runs during this battle. Pourier had known Crazy Horse since at least the early 1870s and stated that he was "as fine an Indian as he ever knew," so the credibility of his observations is beyond reproach. According to Pourier, he saw "Crazy Horse at the Rosebud Creek charge straight into Crook's army, and it seemed every soldier and Indian we had with us took a shot at him and they couldn't even hit his horse."

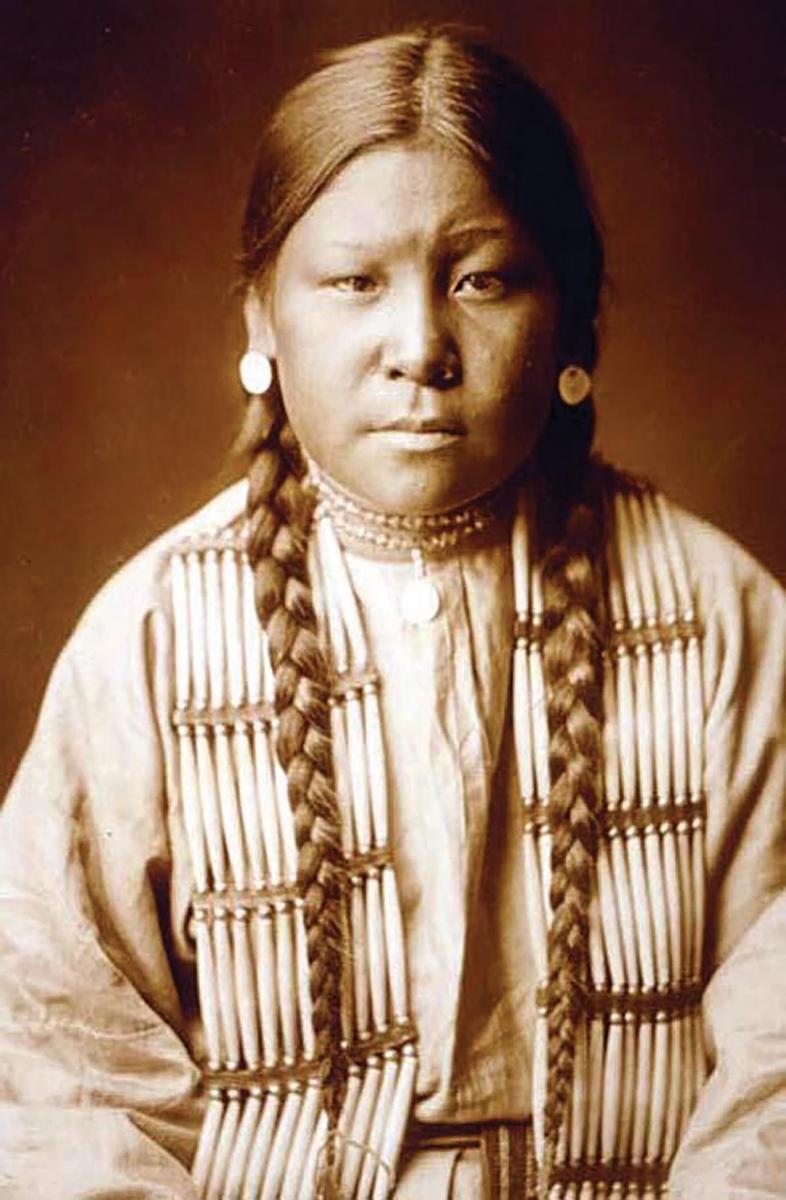

For Northern Cheyennes, one incident has always defined their experience in this engagement. Unscathed by previous bravery runs that he made in the Gap, Comes in Sight was suddenly unhorsed, when his mount somersaulted, one hind leg shattered by a bullet. His sister, Buffalo Calf Road Woman, did not hesitate to ride straight into the teeth of enemy fire and rescue Comes in Sight from what would have been almost certain death. To this day, Cheyenne oral tradition commemorates the Rosebud fight as the battle "Where the Girl Saved Her Brother."

Eight days later, at the Little Bighorn, she distinguished herself once again, when she used her revolver to engage Seventh Cavalry soldiers in a sustained exchange of gunfire. The saga of Buffalo Calf Road Woman did not end at the Greasy Grass. She survived General Randall MacKenzie's attack on November 25, 1876, which destroyed the Northern Cheyenne village located on the Red Fork of the Powder River. She also endured the forced relocation of her people to Indian Territory in 1877 and, the following year, their heroic exodus and return to Montana. Sadly, this mother of two died from diphtheria in May 1879, at Fort Keogh, prior to her thirtieth birthday.

In the final analysis, Rosebud was, at minimum, a strategic loss for Crook. Plenty Coups, however, recounted his experiences in this engagement to Frank Linderman and offered a much blunter assessment: "Three-stars was whipped! And as Washakie and I were with him, we all got whipped good on the Rosebud."

After the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877 concluded, the area encompassed by the Rosebud battlefield was eventually opened to homesteading. Site ownership passed through the hands of several ranching families until Elmer "Slim" Kobold championed its preservation as a state park. That objective was fulfilled in 1978, when the state of Montana acquired 3,052 acres of the Kobold ranch. Subsequent management practices restored the viewshed to one that Jerome Greene et al. (2003) describe as "unspoiled and unparalleled [among] Great Sioux War battlefield[s]."

Rosebud Battlefield State Park is located approximately 20 miles east of present-day Lodge Grass, Montana, and 15 miles north of the Wyoming border. To visit the park, take U.S. 212 east from Crow Agency for 25 miles, then follow State Route 314 south for 20 miles and, finally, the park access road west for three miles.

Leave a Comment Here