Anything Goes

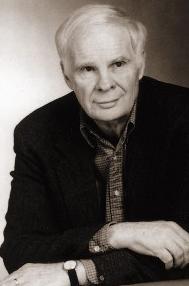

Department Literary Lode

[Excerpt courtesy of Tor/Forge Books. Copyright © 2015 by Richard S. Wheeler]

This was Ming’s Opera House, in Helena, in the young state of Montana, a fancy theater just up the flank of Last Chance Gulch, where millions in gold had been washed out of the earth just a few feverish years earlier.

And now, opening night, the place was half filled and those who had braved the chill mountain winds were sitting on their hands. Who were they, out there? Did they understand English? Were they born without a funny bone? Why had a sour silence descended, a miasma of boredom or ill humor, or maybe disdain, settled like fog over the crowd, what there was of it?

August Beausoleil grabbed a cane and silk top hat, and strutted into the limelight, Big City man in gray tuxedo, in the middle of cold wilderness.

“Ladies and Gents,” he said. “That was the Wildroot Sisters, the Sweethearts of Hoboken, New Jersey. Let’s give them a big hand.”

No one did.

“Citizens of this fair city– where am I?– Keokuk? Grand Rapids? Ah, Helena, the must beautiful and famous metropolis in North America– yes, there you are, welcoming the Beausoleil Brothers Follies.”

Well, anyway, waiting for whatever came next. No one laughed.

“And now, the famed Marbury Trio, from Poughkeepsie, in the great state of New York, doing a rare and exotic dance, a lost art, for your edification.”

It was, actually, a tap dance, and they did it brightly; the dolled-up threesome syncopating feet and legs and canes, as rhythmic clatter that usually set a crowd to nodding and smiling. But the applause was scattered, at best.

Was something wrong? A mine disaster? An election loss?

A bribery indictment? Nothing of the sort had shown up in the two-cent press before the show. The trouble was, the week hung in balance. A bad review, three bad reviews in the three daily rags, and the Beausoleil Brothers Follies would be in trouble.

He eyed the shadowy audience sourly, and came to a decision. He talked quietly to two stage hands, who told him there were few tomatoes this time of year in Helena, but plenty of rotten apples, which would do almost as well.

“Do it,” he said.

“I knew it,” said Mrs. McGivers. “I saw it coming. You should pay me extra. It grieves my soul.”

“I didn’t know you had one,” he said.

Mrs. McGivers and her Monkey Band would follow. Like most vaudeville shows, this one had an animal act, and the Monkey Band was it. Mrs. McGivers, a stout contralto, would soon take the stage with her two obnoxious capuchin monkeys, Cain and Abel, and an accordionist name Joseph. Cain would pick up the cymbals, one for each paw, while Abel would command two drum sticks and perch with a bass drum in front of him.

The master of ceremonies announced the one, the only, the sensational Mrs. McGivers and her Monkey Band, and quick enough she hustled out into the limelight, the little criminals on her shoulders, while Joseph set up the act, the beasts on their chairs, the miniature cymbals, the drum, and finally, his accordion. The audience stared, lost in silence. Would nothing crack this dreary opening night?

Mrs. McGivers had come from the tropics somewhere, and the rumor was that she had killed a couple of husbands, but no one could prove it.

Her repertoire ran to calypso from Trinidad and Tobago, mostly stuff never heard by northern ears, which usually annoyed the audience, which would have preferred bible songs and spirituals as a way of countering the dangerous idea that man had descended from apes. There, indeed, were two small primates, wiry little rascals dressed in red and gold uniforms, making dangerous movements with drumsticks and cymbals in hand.

Once she and her troupe were settled, she turned to Beausoleil.

“You’re a rat,” she said.

Joseph, the accordionist, took that as his cue, and soon the instrument was croaking out an odd, rhythmic tune, and she began to warble stuff about banana boats and things that no one had ever heard of in a nasal, sandpapery whine.

Mrs. McGivers crooned, repeating chords, giving them spice as she and her monkeys whaled away. The Capuchins gradually awakened to their task, led by the accordion, and soon Cain was whanging the cymbals and Abel was thundering the bass drum. The whole performance veered toward anarchy, which is what Mrs. McGivers intended, her goal being to send the audience into paroxysms of delight.

Only not this evening in Helena, in the midst of stern mountains and bitter winters.

Were these louts born without humor?

Very well then. Beausoleil quietly waved a hand from the edge of the arch, a hand unseen by the armored audience.

“Boo!” yelled a certain stagehand, now sitting front-left.

“Go away,” yelled another stalwart of the show, this gent sitting front-right, four rows back.

The Capuchins clanged and banged. Mrs. McGivers warbled. Joseph wheezed life out of the old accordion.

The two reporters, front on the aisle, took no notes.

“Boo,” yelled a spectator. “Refund my money.”

The gent, well known to Beausoleil, had a bag in hand, and now he plunged a paw into it and extracted a browning, mushy apple, and heaved this missile at Mrs. McGivers. It splatted nearby, which was all Cain needed. He abandoned his cymbals, leapt for the mushy apple, and fired it back. It splatted upon the bosom of a politician’s alleged wife.

This was followed by a fusillade of rotten items, mostly tomatoes, ancient apples and peaches and moldering potatoes, drawn miraculously from sacks out in the theater, and these barrages were returned by Cain and Abel.

It was a fine uproar. Suddenly, this dour audience was no longer sitting on its cold hands, but was clapping and howling and squealing. Especially when Abel fired a soggy missile that splatted upon the noble forehead of the attorney general.

After a little more whooping, Beausoleil, in bib and tux, strode purposefully out onto the boards, dodged some foul fruit, and held up a hand.

“Helena has spoken, Mrs. McGivers,” he said. He jerked a thumb in the direction of the wings.

She rose from her stool, awarded him with an uncomplimentary gesture barely seen on the other side of the footlights, and stalked off, followed by the Capuchins, and Joseph, and finally some hands who removed the stools and instruments.

“Give them a round of applause,” Beausoleil said, and immediately the audience broke into thunderous appreciation.

The two bored reporters were suddenly taking notes.

All was well.

* * * *

Richard loves musicals. Here is a song her wrote that goes in spirit with the book:

TEQUILA MARGARITA LYRICS

by Richard S. Wheeler

You’re my Tequila Margarita,

A little salt around the rim

Your hips are swaying to the rhythm

The oldest rhythm in the world...

It’s what gives life

In the morning

I close my eyes

As the evening shadows fall

The warmth I feel

Lying here beside you

I’ll always recall

Chorus

I hear you sing a little love song

And every word is like a kiss

You hips are swaying to the rhythm

The oldest rhythm in the world...

Aye, yi, yi, yi... Aye, yi, yi, yi…

And now the Margarita glass is empty,

There’s not a drop to wet my lips

I have nothing but my dreams and a mem’ry,

Of the swaying of your hips....

Chorus

I hear you sing a little love song

And every word is like a kiss

Your body’s swaying to the rhythm

The oldest rhythm in the world...

Aye, yi, yi, yi... Aye, yi, yi, yi…

(Instrumental)

But my Tequila Margarita,

You linger in my thoughts

You said mañana when I asked you,

But mañana never came...

Never came.

Chorus

I hear you sing a little love song

And every word is like a kiss

Our bodies swaying to the rhythm

The oldest rhythm in the world...

On earth, In heaven, Margarita...

A life that was a kiss

Leave a Comment Here