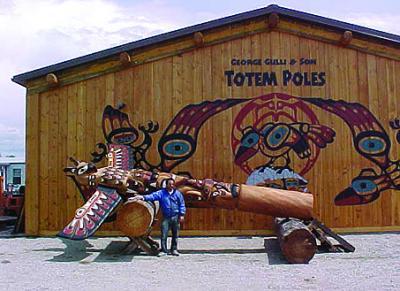

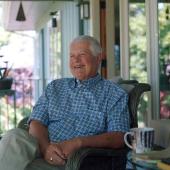

Artist George Gulli

Hand Carved Wooden Totem Poles

Stubby and condensed with muscle, George Gulli’s hands 0direct a sharp blade through thick Western larch, keenly turning a 20-foot log, slowly transforming the lumber into an indubitably magical, profoundly historical, totem pole. On the floor of his Victor workshop, three shorter poles are in various stages of completion from almost done to a log merely shaved, and more than a dozen additional logs await transformation by Gulli’s knives, saws, sanders, chisels and paintbrushes. This is the pinnacle of the western art style.

Short and squat, intelligent and bespectacled, Gulli maintains a set of burly, compacted arms and shoulders which reflect many years of turning humongous logs by hand. Working at an interesting junction of amalgamations, there’s almost no other way of defining him: Gulli’s hands are obligated to past events and previous peoples. Yellowish and hardened by calluses, those hands are unmistakably tied to his Italian ancestry, to his immigrant grandfather who made a life for his family as a stone mason and to his father, George Gulli Sr., who started a totemic art business utilizing the proficiency impassioned through his fingertips.

Furthermore, there’s his self-acknowledged responsibility to the generations of Northwest Pacific Indians who carved poles along the coastal regions of the United States and Canada, and to the prestige and exclusive history of the impressive stories embodied by totem poles. “It’s essentially important to me creating genuine works of art that the tribes find worthy and honorable,” said Gulli, ankle deep in sawdust and shadowed around his workshop by a sawdust-colored dog.

“I’ll never do anything that lessens or hurts the art of the poles.”

Gulli is the “Son” in George Gulli & Son Woodcarving, two miles north of Hamilton, along the east side of U.S. Highway 93; veneration for Native American mores and mythology is itself a family tradition. The story starts the day lightning felled a tree in the California trucking yard where George Gulli Sr. was employed. Since no one offered up a decent suggestion for disposing of the tree, Gulli Sr., whose father had carved stone when he arrived in America from Italy, commenced to carving. The concept had come to him from his brother, an enthusiastic collector of Indian artifacts. “Even though he didn’t know anything about making one,” said Gulli. “He decided to carve a totem pole. That’s how it all began.”

Totem poles, said Gulli, were originally made by Northwest Pacific Coast First Nation’s carvers for their own people, as a way of portraying the sculptor’s deeply meaningful symbols and family crests. To be authentic, a totem pole needs to be “sanctioned.” That means that it must pass certain rigid tests. The pole must be made by a trained Northwest Pacific Coast native person, or in extremely rare cases, a non-Native approved by a Northwest Pacific Coast Band from coastal British Columbia or Alaska.

Over the next few years, Gulli’s father gave presentations of his work and provoked the resentment of certain purists who “believed that only an American Indian had the authority to carve these ancient cultural symbols of Northwest tribes.” Then, Chief Mace of the Northwest Coast Indians in British Columbia heard of the protesting, Gulli said. The Native leader inspected the man’s efforts and found them to be commendable representations. ”We’ve both been scrutinized pretty thoroughly,” he said.

To Gulli, the line between authentic and fake totems is patently clear. “Chain saw artists, non-Native imitators, and Natives from bands far away from the Northwest Pacific Coast claim to produce totem poles. But under Northwest Pacific Coast totemic rules and traditions, they are fakes. To be a true totem pole, rigid requirements need to be met.”

Gulli has learned the significance of the poles, the way they communicate family stories, characterize death, and lionize spoken historical recollections for generations to come. “It’s truly in the unique language of carving,” Gulli said. “I feel honored and compelled to do it. And there’s a sense of harmony and peacefulness to it.”

And while it’s often said that you can read a totem pole, that’s only partially true. Opposite of prevailing belief, an individual totem pole cannot actually be “read like a book,” even by crackerjacks in Northwest native art. No one but the artist, said Gulli, can read a totem pole because of the varied meaning the symbols can have. Such inveterate symbolism and inherent meaning has to be explained by the carver to the owner of the totem pole, traditionally at the time of the pole raising.

It took ample time for those skills of George Gulli Sr., to become his son’s. George Jr. spent a sufficient amount of his life discovering what he wanted to be. In that aspect, his life resembles his father’s. The senior Gulli worked in the trucking industry for more two decades until the tree fell down. Then, within a matter of years, he found himself working for the Marriott Corp., which was building theme parks and wanted totem poles as part of the parks’ scenery. Gulli moved to Montana with his father and mother in 1982. Eventually, the younger Gulli took a significant interest in his dad’s business, sometime in the early 1980s, and true to the carver trade has remained industrious and immersed.

“Even though I grew up around totems and wood carving, I didn’t have the patience for it until I was 25. From 25 on, I was so ambitious to learn the skills of carving that I would roll my dad out of bed at 6 a.m.”

Through the 1990s, Gulli spent his days helping his dad with poles while working assorted jobs, and finally, in 1993, after his father had triple bypass surgery, was filling customers’ orders on a full-time basis. For the remainder of the decade, Gulli researched and contemplated the traditions and techniques involved in totem making, while barely scratching out a living to support his wife, Vonni, and their three children.

Although George Gulli Sr. died in 2000, his son has kept the family business vital, turning out about 30 poles a year, ranging from head-tall to more than 50 feet. Prices range from $100 to $300 a foot for a pole, depending on the depth and width of the log and the amount of exertion involved. Today, Gulli has enough customers that he has a two-year waiting list.

These circumstances are not lost on Gulli, who has spent more than a little time mulling over the juxtaposition of craftsmanship, history and commerce. “It’s truly amazing that a California truck driver came to the realization that carving totem poles was his real life’s work,” said Gulli, working on his latest pole, hands guiding the chisel into the golden proboscis of a tamarack, translating wings and animal faces where there once was timber.

“Art is just a funny business,” Gulli said of the erratic and extravagant actions of his trade. “To me, art has become the search for perfection.”

Next to a small black and white portrait of his own hands, George Gulli keeps an even larger framed picture of his father’s. After remembering how as a child he watched the magic those hands could impart, Gulli said, just like his father, that he plans on working up to his last day. ”Actually, there’s still some of his unfinished stuff lying around, but I don’t have the heart to complete it,” said Gulli, rubbing sawdust particles from the corner of one eye. “Honestly, my father deserves all the credit for everything I’ve done.”

~ Brian D’Ambrosio is a freelance-writing, dog-loving Missoulian, also working as a preschool teacher and food caterer, bartender and boxing referee.

Leave a Comment Here