The Band Boys of Butte: Montana's Best Brass Band and the Tycoon Who Never Bought a Man Who Wasn't for Sale

In 1887, the Boston & Montana Band held its first rehearsal in the log cabin of miner and horn player Joe Ivey. Lit by dim oil lamplight, warmed by logs crackling in a potbelly stove, Ivey and five other Cornish employees of the Boston & Montana mining company made a racket that rattled windows. The cavernous oom-pah of Tom Burt's tuba harmonized with Ivey's and Charles Griffin's horns, the clarinet of Jack Carbis, and the cornet of band leader Sam Treloar. Bill Jennings drummed.

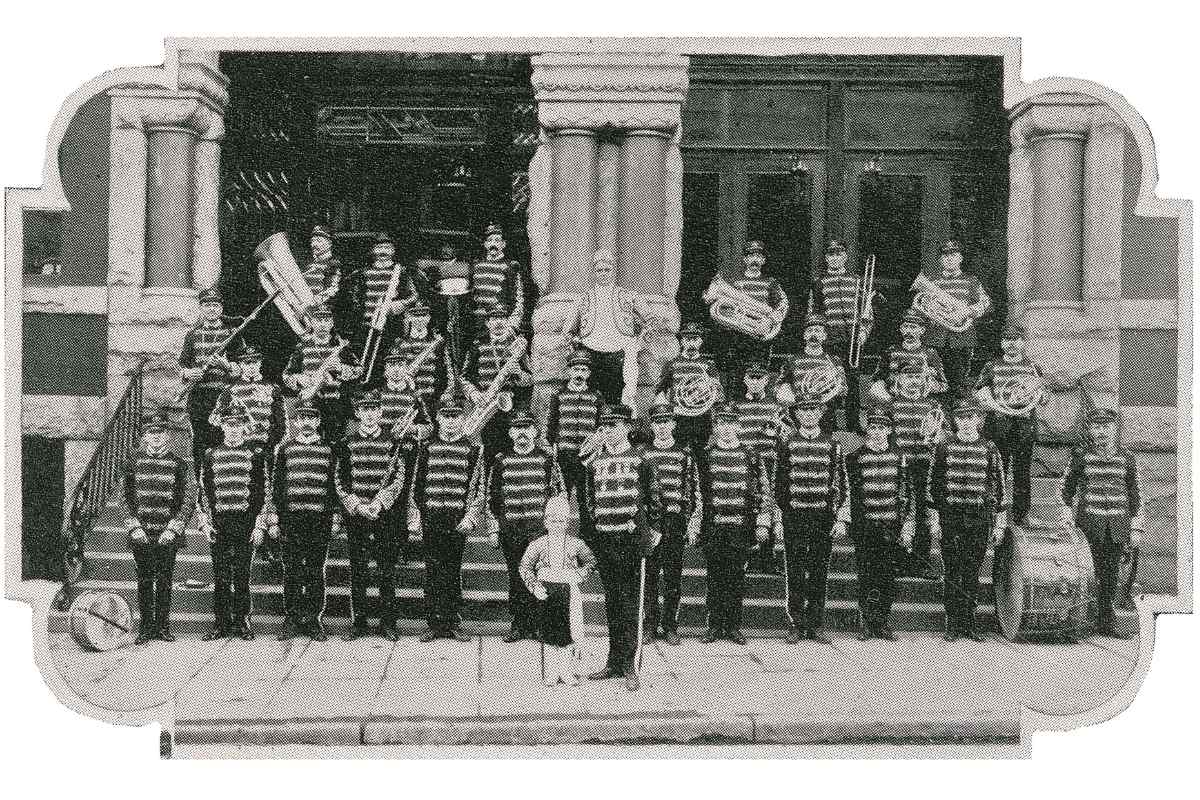

As Treloar, 21, standing little over five feet, led them, other residents of the Butte suburb Meaderville crammed into Ivey's cabin to observe. These spectators could not have foreseen that this crude ensemble would become one of America's great bands. Or maybe they could.

The Boston & Montana (B&M) Band rose to fame through talent, hard work, Treloar's brilliance as a director… and help from William A. Clark.

Despite Clark's well-known fraudulence, the band had him to thank for their renown. They lent their excellent music to his causes. He offered great exposure. The Montana Historical Society's collection of band records and a survey of historic Montana newspapers reveal this synergism.

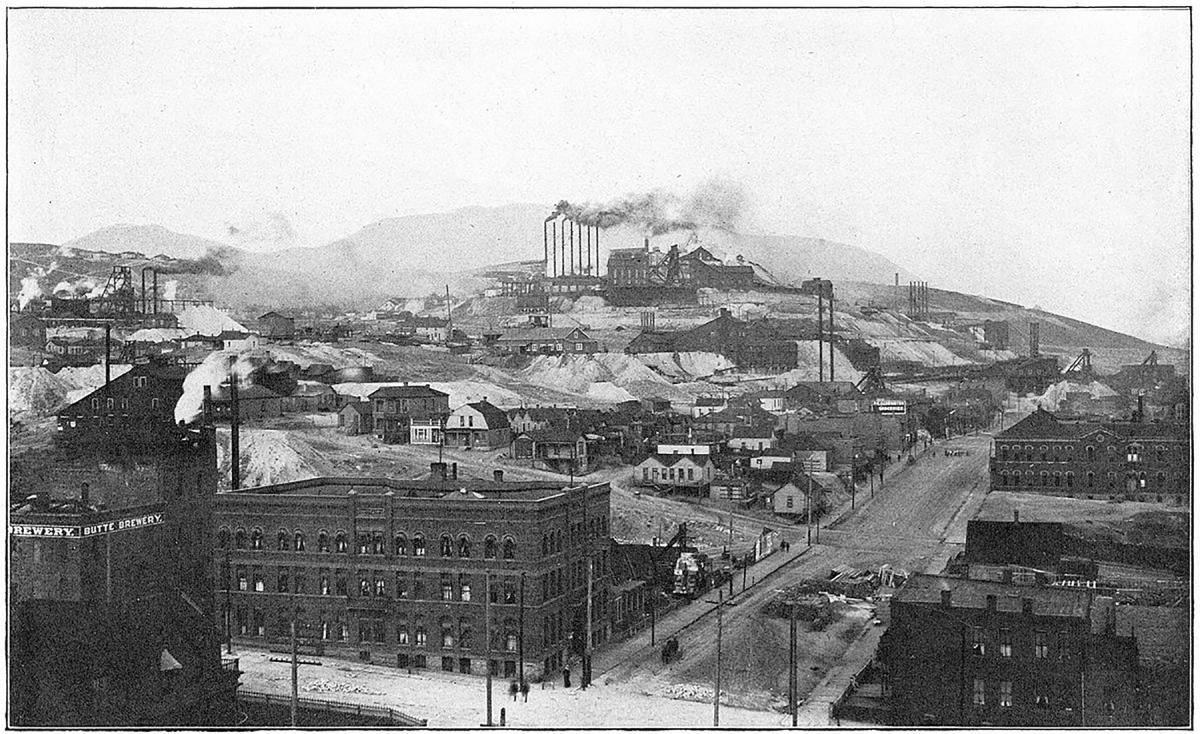

Clark came west, leaving an Iowa schoolhouse. He hit pay dirt in the 1863 gold rush before making a fortune as a Deer Lodge banker and funding Butte's early industrialized mines. In the 1870s, his business decisions made Butte, then a languishing gold camp, a real city. By the late 1880s, Clark owned many mines, a smelter, the Butte Miner newspaper, and the local street rail. He possessed political ambitions too.

Sam Treloar directed the B&M Band for sixty years. He composed and arranged music, held office as a legislator, conducted Deer Lodge's band of prison inmates, and had worked every mining position from mucker to superintendent.

When Britain's mining industry tanked, teenage Treloar emigrated to the U.S. with his widowed father Tommy. Sam mined in the Black Hills as the Frontier Wars raged then in Leadville, Colorado. Tommy, meanwhile, lived in Butte. He worked for "Captain" Thomas Couch, a childhood friend from Cornwall. Couch managed a new mining company, the Boston & Montana. Before long, Sam lived in Butte with his father, mining at the Boston & Montana's East Colusa.

This band formed because the company faced a crisis. In 1887, no streetcar connected its headquarters Meaderville with the rest of the city. The isolated borough lacked entertainment. So, Boston & Montana miners, Meaderville's chief workforce, hiked two miles to patronize Butte's city center nightlife. If they came to work the following day, they arrived late, suffering a skull-gnawing hangover that only Old West Butte could inflict.

By the late 1800s, over 200 saloons, like the Graveyard, Cesspool, and Bucket of Blood, served a population of around 10,500. Plentiful establishments furnished gambling. And red lights burned, according to the Butte classic Copper Camp, on East Galena Street, where French Erma, Austrian Annie, Jew Jess, Mexican Maria, and Mickey the Greek worked.

Boston & Montana's productivity suffered.

Couch and Treloar thought a company band might help. Members would keep their noses clean and be excused from the graveyard shift—incentivizing employees to master an instrument posthaste.

The B&M Band created a local sensation.

It seems odd now that a mining company would have its own band that could command such attention. Bands, though, once purveyed the most popular American music. The adoration now seen for pop stars Americans once exhibited for brass bands. Audiences loved occupational bands. As well as miner bands, there were dentist, farmer, cowboy, factory, and newsboy bands. Patients in insane asylums even formed bands, according to scholars Margaret and Robert Hazen.

Clark and the B&M Band's symbiotic relationship began in 1888. Clark ran as a Democrat for the Montana Territory's delegate to U.S. Congress. The B&M Band marched in his Election Day Eve parade with other bands and flame-juggling flambeau clubs. As part of the festivities, Clark, trying to court Cornish voters, hired this new Cornish band to stand by at Renshaw Hall. They played patriotic music to glorify Clark's pro-labor, pro-tariff-reform, anti-Chinese speech.

Clark felt confident he would win. After seeing the election results, Clark believed his foe, Anaconda Company mogul Marcus Daly, rigged the election.

Clark next sought the U.S. Senate after Montana's 1889 statehood. To add insult to injury, Daly cost him another election. Legislators, not the voting public, sent senators to Washington at the time. So, in 1893, Clark bribed them for votes. Daly found out. He offered the legislature more money for votes against Clark!

Clark saw his opportunity for vengeance in 1894, when voters decided between Helena or Anaconda as the state capital. Clark knew how badly Daly wanted Anaconda, home of his smelter, to win. Clark championed a campaign for Helena to end them all. The two dumped exorbitant sums into their "Capital Battle." Between all the pro-Helena or pro-Anaconda rallies, parades, and demonstrations, Montana bands had never been busier.

When Helena won by less than 2,000 votes, the B&M Band rode with Clark on his private train to celebrate. As they stepped out at the Helena depot, cannons fired. When Clark climbed aboard the wagon to take him to the city center, a crowd unfastened the horses to personally pull his buggy. The band followed Clark in an impromptu parade through the new capital.

After the sun went down, the real celebration unleashed itself on Main Street. As many as fifteen thousand spectators lined the streets. The air smelled of gunpowder from all the fireworks. The B&M Band took the coveted lead spot in the parade. Five other bands marched. So did flambeau clubs, a Goddess of Liberty, and Helena's Afro-American Capital Club. The festival culminated at Helena's Auditorium, where the band played to accompany Clark's speech. He compared Daly to Napoleon and Anaconda's loss to Waterloo.

Clark came calling again in 1896, as America recovered from economic depression. With the Panic of 1893, silver was federally demonetized. This devastated the West, dependent on silver mining. A new political coalition formed. Western Democrats, "Silver Republicans," and a new party, the Populists, fought for silver's return to currency. Their hope lay with presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. Clark, the owner of many silver mines, led the Montana Delegation to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. For good P.R., he invited the B&M Band along.

The B&M Band rode with Clark and delegates on the Northern Pacific's "Silver Special." Heading east, the train stopped at every Montana depot, where crowds gathered to hear a tune.

After the four-day journey, the band stepped from the train into a Chicago summer's thick, moist heat—grueling in their black wool coats. Buildings that made Butte's Hoffman Hotel seem like a country mercantile cast shadows that stretched blocks. A throng of Democrats gathered to meet the Montana envoy. Treloar struck up the band for Sousa's "King Cotton" march, and they paraded delegates to their headquarters at the seventeen-story Auditorium Hotel.

As the convention proceeded, they performed in various hotel lobbies. They rubbed shoulders with esteemed Chicago bands. They impressed audiences, at one concert honoring a request for "The William Tell Overture." They entertained prominent politicians, even William Jennings Bryan. Anywhere they went, Clark made sure to introduce them as miners. At DNC headquarters, the Coliseum, this "Montana Miners' Band was blowing all the power of its lungs into its brass horns," wrote The Baltimore Sun, after the announcement came that Bryan would run against William McKinley.

The band boarded the Silver Special home as heroes to their state — and the silver movement. Minneapolis' pro-silver Penny Press, enamored with the "Boston & Montana Silver Band," wined and dined them when they stopped in Minneapolis to give a concert at a lakeside park for a lemonade-sipping crowd of hundreds.

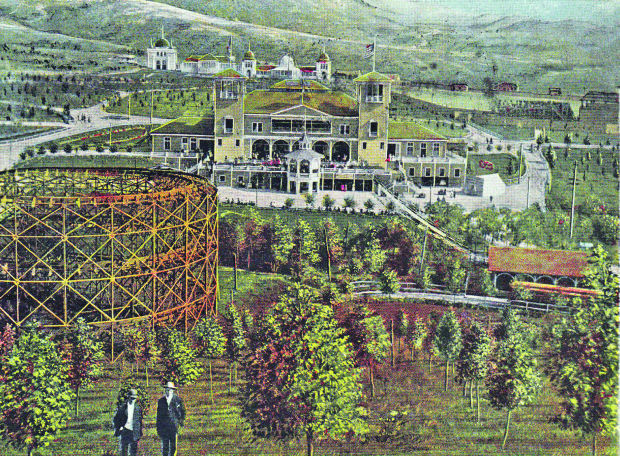

In 1899, Clark bought Columbia Gardens, a failed mining claim turned failed amusement park. He publicized that he made this purchase to offer families a refuge from the grunge and toxic smelter smoke of Butte. To give back to the community, he had a blank check to develop the land into a world-class resort for which he would charge no admission. Yes, he was running for office again and badly needed to endear himself to voters.

In 1899, Clark had actually bribed his way to the Senate…for a few days. Daly, despite failing health, ensured Clark faced a Senate investigation, which found him guilty. He resigned in a fit before he could be removed. Amazingly, Clark ran again in 1900, the Gardens one ace in his sleeve. He set off on a "tour of the state seeking vindication." Clark toured with "his band," receiving "$6 a day and all expenses," according to one of the many press stories quoted by C.B. Glascock in War of the Copper Kings.

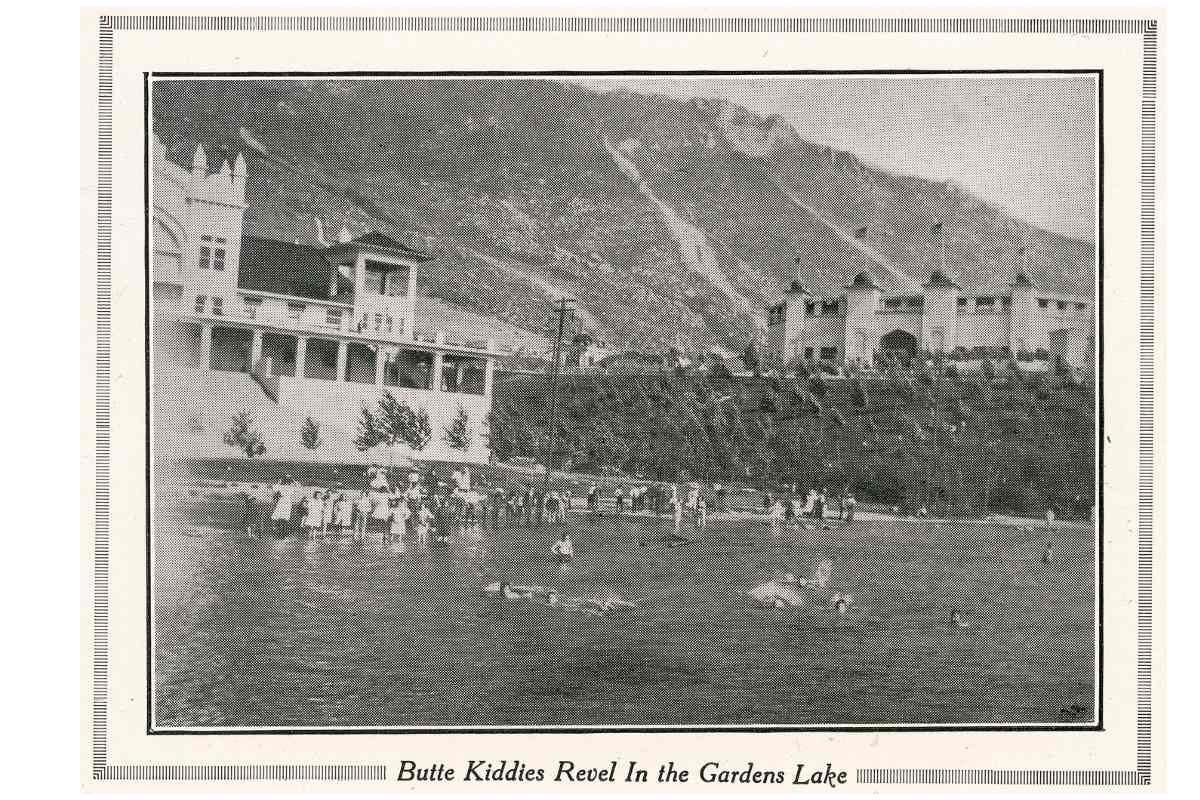

In its heyday, Columbia Gardens held manicured flower beds, greenhouses, an ice cream parlor and café, a baseball diamond and grandstand, a mechanical chute ride, and a roller coaster. Its dance pavilion featured fountains, flower baskets, and a 62,000-foot dance floor, lit by incandescent lights and Japanese lanterns. Clark's management contracted the B&M Band, by this time a huge draw, to play at the Gardens three times a week: for Thursday Children's Days, Sunday afternoon sacred music concerts, and Sunday evening dances. Treloar composed the "Columbia Gardens March." Thousands, from all over the region, attended these performances.

Clark hired the band to play for another DNC, too, in Kansas City. But this time Boston & Montana management forbade the band from going.

The Boston & Montana considered F. Augustus Heinze, with whom Clark had aligned for his senatorial campaign, their arch-nemesis.

The "Courthouse Miner" Heinze's latest offense against the Boston & Montana: he sued to shut the company down over a property boundary dispute. While his lawsuit rendered them inert, Heinze mined what they claimed was their ore. Heinze had made enemies of Daly and his business partners using similar tactics. Any enemy of Daly's was a friend of Clark's.

Not all band members even worked for the Heinze-hating Boston & Montana in 1900. But the company would fire the 15 that did if they went to Kansas City for their support, however inadvertent, of Heinze.

These band members cut their losses and went, creating a media blitz. The conflict even reached The New York Times. The newspapers Daly and associates controlled cast the band as tragically beholden to Clark and Heinze's crooked politics. Clark and Heinze's mouthpieces depicted the band as patriots resisting corporate tyranny.

After the band told management they were going, the company cut the power to their rehearsal hall.

The Kansas City DNC cost half the band members their jobs, but it gave terrific national exposure. While delegates headquartered at the Midland Hotel, the band stayed next door in a brownstone mansion owned by the Elks. They gave daily open-air concerts from its wraparound porch. They made big news by stopping at William Jennings Bryan's Nebraska home on the way back to give him a midnight serenade.

Interestingly, Clark led only one Democratic delegation from Montana. Daly supporters came as a separate faction. The party had to decide which Montana delegation to recognize as legitimate. When they chose Clark's, the band played a "hilarious" victory party at the Midland Hotel lobby. They kicked off the night with "Hot Time in the Town Tonight." Anti-Clark papers portrayed the celebration as salacious, citing drunkenness, interracial dancing to ragtime music, and gunfire from horseback riders accompanied by prostitutes.

Daly, near the end of his life, merged his Anaconda company with eastern capitalists tied to the megalithic corporation Standard Oil — an unpopular decision. Clark's anti-Standard Oil position, bolstered through his alliance with Heinze, in part won him the election. Clark did not have to bribe for his U.S. Senate seat. In 1900, Daly passed away at 58. Clark took office in 1901 and served a full term.

Clark no longer needed the band and stopped paying and promoting them. His days of throwing parades in the name of political ingratiation were over. He abandoned Heinze, too, and any other ally who no longer proved useful. He even sold his mines to his purported Standard Oil-embroiled enemies. The Elks took the place of Clark for the band's national exposure. They competed in big-city Elks band contests and won several.

Through World War I, they played for America's patriotic movement. In addition to other world leaders, they performed for almost every U.S. President in the first half of the twentieth century. John Philip Sousa, the band music king, numbered among their countless fans. They persisted into World War II, but old age caught up with Treloar. The draft took many band members overseas. Butte made wartime cuts to its civic entertainment budget. In the 1940s, people were swing dancing instead of foxtrotting or polkaing at Columbia Gardens, which booked new touring bands led by the likes of Benny Goodman or Tommy Dorsey.

Both Clark and Treloar lived into their eighties. Clark died in 1925 in New York City and Treloar in 1951 in Los Angeles. Although the two were not personally close, their careers could not have unfolded as they did without each other. When it mattered, Treloar and the band made Clark look good. Clark did the same for them. They had a special way of legitimizing each other. This alliance gave the B&M Band a huge audience — and a first-row ticket to decades of momentous historical events.

Leave a Comment Here