Montana and the Nez Perce Flight for Freedom

On July 25th, 1877, some 800 Nez Perce crossed Lolo Pass into what is now Montana and made camp around Lolo Hot Springs. Included were about 250 warriors, with the rest being mainly women, children and elders. They brought with them more than 2,000 horses and all the gear needed to start a new life in exile.

They were leaving behind their homelands in northeast Oregon and Idaho: lands promised to them in their treaty of 1855, but taken away by the "new" treaty in 1863. This new treaty shrunk the Nez Perce Reservation to a small fraction of the original allotted territory. The discovery of gold will do that. The exiles were members of the bands that lived outside of the boundaries of the new treaty, negotiated without their input or consent. They refused to recognize the new treaty and would henceforth be known as the "non-treaty Nez Perce," a distinction that remains within the tribe to this day.

It had been 73 years since the Nez Perce had greeted Lewis and Clark with friendship and pledged peace with the U.S. government, thinking they would get the same respect in return. They were now retracing the Voyage of Discovery's route back through the rugged Bitterroot Mountains on a flight for their lives. Ironically, among them was the 72-year old son of Captain Clark. Along the way they had already successfully fought two battles and several skirmishes with General O.O. Howard, an ex-Civil War soldier who was tasked with getting all Nez Perce onto the new reservation.

To these Nez Perce, Montana meant freedom—a place to start anew. They had left Idaho, so they didn't think Howard or the government would bother them here. This was also familiar territory. Nez Perce hunting parties headed east over these mountains to the plains for buffalo for generations. Over the years they had made friends here—friends they thought would help them now. Among those were the Bitterroot Salish, the recent white settlers of the Bitterroot Valley and the Crows to the east. However, neither the Salish nor the Crows would offer aid and assistance, fearing retribution from the government. The white settlers were happy to do business with them and take their money, but were glad when they moved along.

Times and technology were changing rapidly in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The exiles were unaware of the telegraph, allowing communication over vast distances at nearly the speed of light. Through this, the military were able to keep track of them, mobilizing unit after unit along their way and giving them no rest. Through it, their whole struggle also played out in the newspapers and tabloids of the time. The whole country was following, like a modern-day reality show. They were becoming cult heroes, especially Chief Joseph.

There could be no peace for them in Montana. It was only a year earlier that Sitting Bull had defeated Custer. This band of "renegades" must be made to feel the full boot of the military and brought into line, lest other tribes sense an opportunity for freedom and they have a full-scale uprising across the West. They had not left Howard permanently behind and he would, indeed, continue to pursue them across Montana over the next few months. The military must not be bested again. But bested they were at each encounter. Even at the end it was less of a military defeat and more of a standoff where Chief Joseph felt surrender was in the best interests of the children, elders and wounded remaining. For a people who had never engaged in warfare with an organized military before, the tactics of the Nez Perce were surprisingly astute and effective.

As the old saying goes, "hindsight is 20/20." There were blunders on both sides. Howard proved to be a less than competent tactician, and was often found to be days behind the band. Outrunning his forces was not difficult. The Nez Perce could have easily made it were it not for puzzling errors of their own, that went along with their brilliance in battle.

Although history (and the military) considered Joseph as the overall leader, he was not. His brother, Ollokot, was the war chief of the Wallowa Band, while Joseph was responsible for the safety and health of the whole group. Other bands were led by Looking Glass, Toohoolhoolzoote, and White Bird. In addition, there were some smaller, affiliated bands from the neighboring Palouse Tribes. Among the leaders there was a consensus to appoint Looking Glass to the lead position. Looking Glass was a brilliant tactician in battle, but some of his other decisions were disastrous.

After peacefully moving south through the Bitterroot Valley, the exiles camped along the North Fork of the Big Hole River, just west of present-day Wisdom. They were tired, and there was good forage for the horses and camas bulbs for food. Looking Glass sensed no danger, having left General Howard behind. Others, such as White Bird, tried to press a sense of urgency, but Looking Glass turned a deaf ear to it. He didn't even post any scouts.

In the meantime, Howard had already telegraphed Col. John Gibbon at Fort Shaw, west of Great Falls, to intercept the Nez Perce and force their surrender. During the pre-dawn hours on August 9, 1877, Gibbon's small force of fewer than 200 men attacked the encampment, firing low into the teepees. Their barrage of bullets killed mainly women and children who were sleeping there. Joseph acted quickly to save the horses from stampeding, and the warriors conducted a successful counter offensive, holding Gibbon's men at bay for a day and a half while they packed up camp and left. Later, Gibbon would say that the war was "an unjustifiable outrage upon the red man, due to our aggressive and untruthful behavior towards these poor people."

The Nez Perce now headed east, through the newly formed Yellowstone National Park. Again, feeling no particular urgency, and needing to build up their horses' strength once more, they tarried there for two weeks. It was there that they learned the Crows were not going to help them, so they decided to head north to the "Medicine Line." Once again, they eluded forces dispatched to meet them exiting the park and began a more direct route to meet up with Sitting Bull in Canada.

They arrived at the banks of Snake Creek in the Bear Paw Mountains on September 29. They were now barely 40 miles south of the border. People and horses were tired. Knowing they were days ahead of Howard, they had been moving rather slowly. Looking Glass again did not listen to counsel to keep moving and posted no guards that night.

In the meantime, Howard had telegraphed Col. Nelson Miles, stationed in eastern Montana, to set out as quickly as possible to intercept the Nez Perce before they reached Canada. He also arrived in the Bear Paws on September 29th, with 520 soldiers and about 30 Indian scouts, mainly Cheyenne, and camped about six miles south of the Nez Perce encampment.

The morning of the 30th broke cold—snow was in the air. Miles ordered a cavalry charge on the encampment. His Cheyenne scouts, with a small contingent of soldiers in tow, made for the prized Nez Perce Appaloosa horses that they were promised. Joseph again tried to save the horses, but only succeeded in corralling a fraction of them this time. Without their horses, the Nez Perce lost their mobility and were trapped. A group of Nez Perce, mainly women and children, escaped that night to continue to Canada. The rest regrouped and a siege between the two sides set in. It was getting colder and snowier—typical for that time of year in northern Montana. They were freezing and hungry, hunkered down in hastily dug rifle pits. Both sides wondered what Sitting Bull would do. Was a rescue coming?

By the night of October 4th, chiefs Ollokot, Looking Glass and Toohoolhoolzoote had been killed, leaving only Joseph and White Bird. Joseph realized help wasn't coming from Sitting Bull and it was in the best interest of his people to surrender, while White Bird wanted to break through the army's lines and still try for Canada. White Bird and about 50 followers slipped out of the encampment under the cover of darkness and, meeting up with those who left earlier, made their way to Sitting Bull's camp. After traveling so far and enduring so much, it must have been truly heartbreaking to come so close and now have to surrender.

On October 5th at about 11 a.m., Joseph, the sole remaining chief, walked out of the encampment and formally surrendered to Miles and Howard, who had finally arrived. He turned over his rifle and made his now-famous speech, poetically translated as, "From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever." Four hundred and thirty-one people, mainly women, children and wounded, surrendered that day, and just under 300 Nez Perce made it into Canada. Joseph later said, "We could have escaped from Bear Paw Mountains if we had left our wounded, old women, and children behind. We were unwilling to do this. We had never heard of a wounded Indian recovering while in the hands of white men."

Miles and Howard had promised Joseph that they would be returned to Idaho. However, General Sherman of Civil War fame, who was by now the commanding general of the Army, vowed over protests from Miles and Howard that Joseph would never be allowed to go back home. The captives were first taken to Bismark, North Dakota, then to Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, before being relocated to "Indian Country" in Oklahoma.

During that time, Joseph was a constant advocate for their freedom. He was allowed to travel back to Washington D.C. to press his case. He even had an audience with Congress and President Hayes. While there, he gave an interview with the editor of the North American Review, explaining the plight of his people. "We should have one law to govern us all… All should be citizens of the U.S. Let me be a free man, free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to talk, think and act for myself— and I will obey every law or submit to the penalty." Why did the government, that preached freedom to all Americans hold his people "as you keep animals in a corral?" In the end it was to no avail.

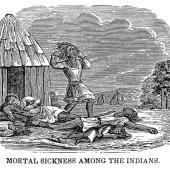

Finally, after seven years in the "hot country" of Oklahoma, the 268 remaining Nez Perce, numbers decimated by disease, squalor, and neglect, were allowed back to the Northwest. About half were allowed back to Idaho, but not Joseph. He and the other remaining Nez Perce were relocated to the Colville Reservation in northeastern Washington. He passed away in 1904 and is buried there.

He is credited with saying: "I believe much trouble and blood would be saved if we opened our hearts more." A sentiment that rings as true today as it did in 1877.

Leave a Comment Here