The White Swan Robe: A Tribute to Anonymous Nineteenth-Century Plains Indian Artists of Montana

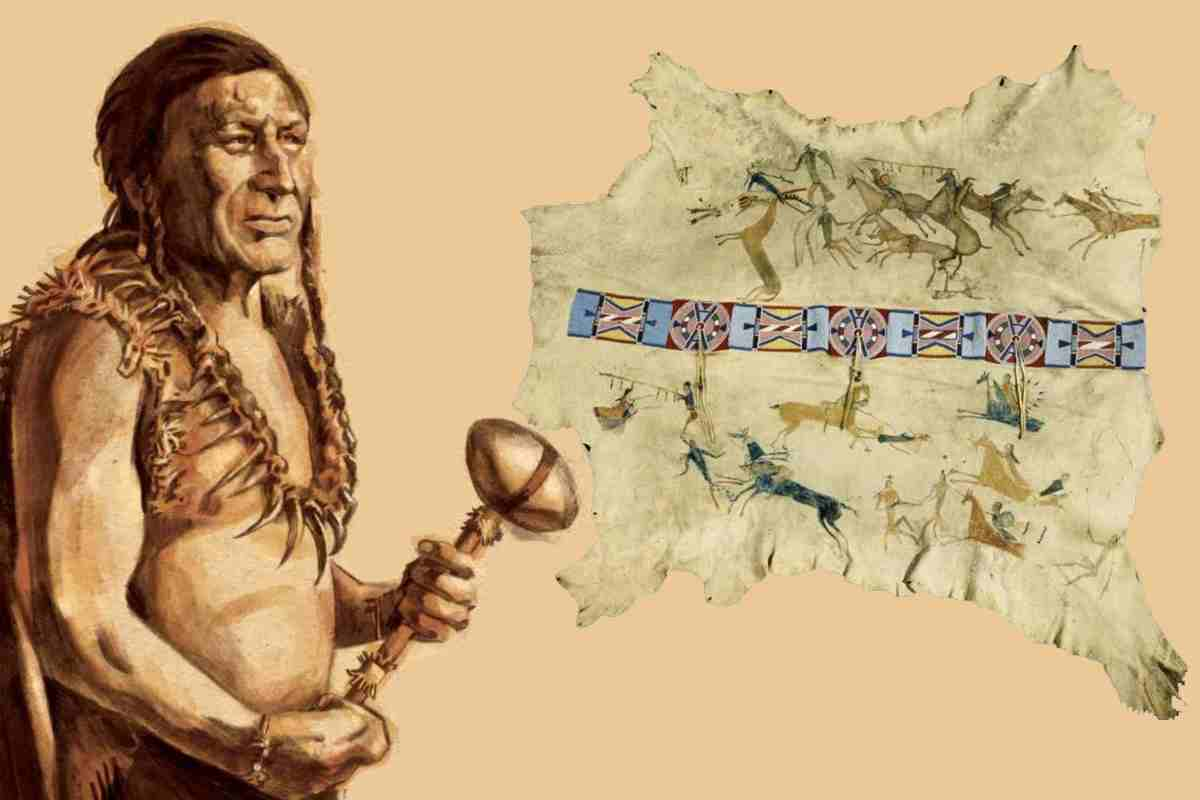

The artistic legacy of Montana's nineteenth-century Plains Indians was, with few exceptions, bequeathed anonymously to posterity. Stylistic signatures, however, frequently convey the tribal affiliation of these artists whose identities were not recorded. A war-exploit robe in the collections of the Montana Historical Society, which they attribute to White Swan, an Aspaalooke (Crow), is uniquely qualified to represent these artists of the past, since it is embellished in a style that exemplifies artforms produced, respectively, by Crow men and women.

The most prolific Crow warrior-artist of his generation, White Swan was one of six Crow scouts detached to Lt. Col. George A. Custer's regiment on June 21, 1876. White Swan saw extensive combat in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where he was severely wounded. He recovered sufficiently from that conflict to chronicle his military career in artworks. This robe, however, was devoted primarily, if not exclusively, to honors achieved in intertribal warfare.

Warrior art from the reservation period typically communicated four facts about each exploit: tribal and/or personal identity of the protagonist, the affiliation of the adversary, the outcome of battle, and the relative odds associated with that encounter. Ironically, it is sometimes easier now to determine the tribal affiliation of the protagonist, especially if the artist emphasized idiosyncratic features, such as hair styles or specific aspects of warrior-society regalia, as heraldic devices.

Statements of place remain a pictorial lexicon. In biographical art rarely employed by the Aspaalooke, the figure trait illustrates the pompadour hairstyle, loop necklace, and panel leggings. Other features, including depictions of pitched hair extensions, and the application of red paint to the forehead, are representative of Sioux tribesmen. Yet these traits were used similarly by Lakota and Cheyenne artists to identify their Crow adversaries.

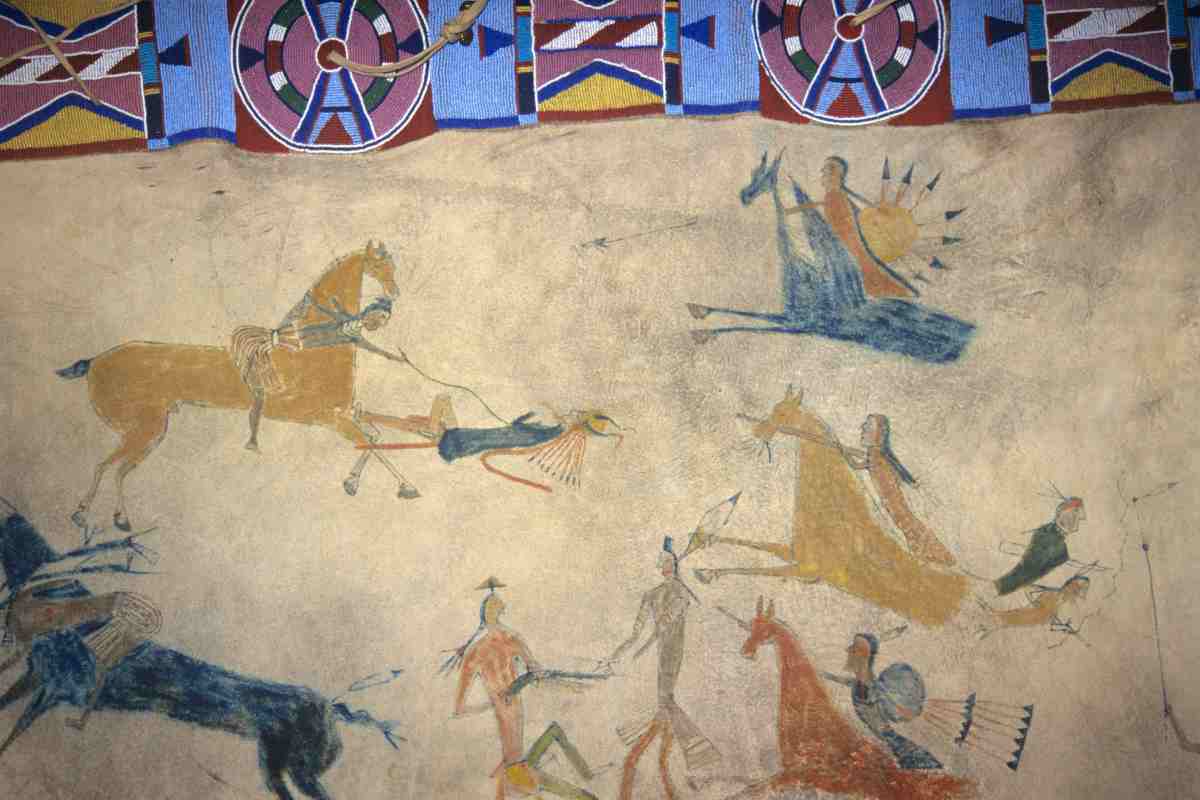

During an addition, the accumulation of four specific honors was necessary to become a chief: leadership of a successful war party, capture of a horse picked in an enemy village, seizure of an opponent's weapon in hand-to-hand combat, and the formal act of "counting coup," which involved physically touching or striking an enemy. Three of these four accomplishments are depicted on the White Swan robe and will be focal points of analysis.

Two vignettes, located directly below the central and right rosettes of the beaded blanket strip, illustrate coup-strike encounters. In the upper vignette, White Swan reaches down from his horse to count coup on a fallen en foe, one clad in a split-horn bonnet that is trimmed with ermine tails and decorated with a cluster of red trade cloth. This artifact is one of the earliest examples of the warbonnet style that became common in the early 1880s, that ermine-fringed, split-horn bonnets were exceedingly rare and worn only by the most distinguished warriors. Indeed, the renowned Mandan, Mato-Tope ("Four Bears"), was then the only tribal member entitled to wear this type of headdress.

The significance of White Swan's gun-capture exploit, on the other hand, is indicated primarily by the exaggerated size of his coup feather. White Swan minimized material expressions of his adversary's ethnicity, perhaps, to focus the viewer's attention on the simple act of seizing his weapon. The danger associated with this feat was augmented by the rapid approach of a mounted and armed enemy.

The most intriguing composition, which appears on the robe's upper left corner, depicts the successful capture of an enemy horse, tied only to the mounts lost by a fallen warrior. This coup, a fundamental prerequisite to chieftainship. Horses tethered in this manner were, invariably, the most highly prized ponies in any encampment.

A discrepancy in the protagonist's regalia raises the possibility that this horse was, indeed, a "bullet runner," one reserved for the chief or another battlefield. The artist's pompadour, panel leggings, and pitched hair extension are consistent with technological attributes that pinpointed his tribal affiliation while accentuating his Crow ancestry.

Statements by Ghost Head, a Lakota artist, support this interpretation. Emphasizing that he always took enemy clothing on horse raids, Ghost Head expounded upon this point with the following observation:

"Had it been a Shoshoni camp, I would have worn Shoshoni clothing, so that I would have smelled like a Shoshoni and painted my face and fixed my hair so that I would not be noticed."

The White Swan robe's blanket strip is a veritable textbook on classic Crow beadwork, but Aspaalooke ownership of their material culture does not necessarily negate evidence of their distinctive style of beaded art. In 1805, Francois-Antoine Larocque observed that Crow men owned, as "Buffalo Robe on which is painted their war exploits or garnished with beads and porcupine quills [were] the seam." Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied reported similarly, in 1833, that Crow buffalo robes were "painted and embroidered [with] dyed porcupine quills." In Karl Bodmer's portrait of Crow Man rendered in 1833, one figure is cloaked in a buffalo robe beaded with a geometric design. Additional evidence can be found in period photographs, which further strip illustrate the texture of Crow stitch embroidery. While stationed at Fort Union, Rodolph Friederich Kurz received, as a gift, a buffalo cow's hide, obtained originally from the Crow on September 15, 1851. Kurz described its ornamentation as "a broad band, decorated with beads, porcupine quills and tiny bells that hang from rosettes." Edwin Denig, an authority on Missouri tribes at that time, wrote: most probably in 1856, that bright-colored blankets, traded with beads worked curiously and elegantly across them, [were an important part of regalia worn by young Crow [men]."

Despite historical and pictorial evidence that Crow usage of this object type persisted throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, well-documented examples and archival photographs indicate that the vast majority of Transmontane-style blanket strips should be attributed to Plateau peoples, most commonly the Nez Perce, with whom the Crows traded extensively. So, what features enable us to conclude definitively that this particular blanket strip was crafted by Crow beadworkers?

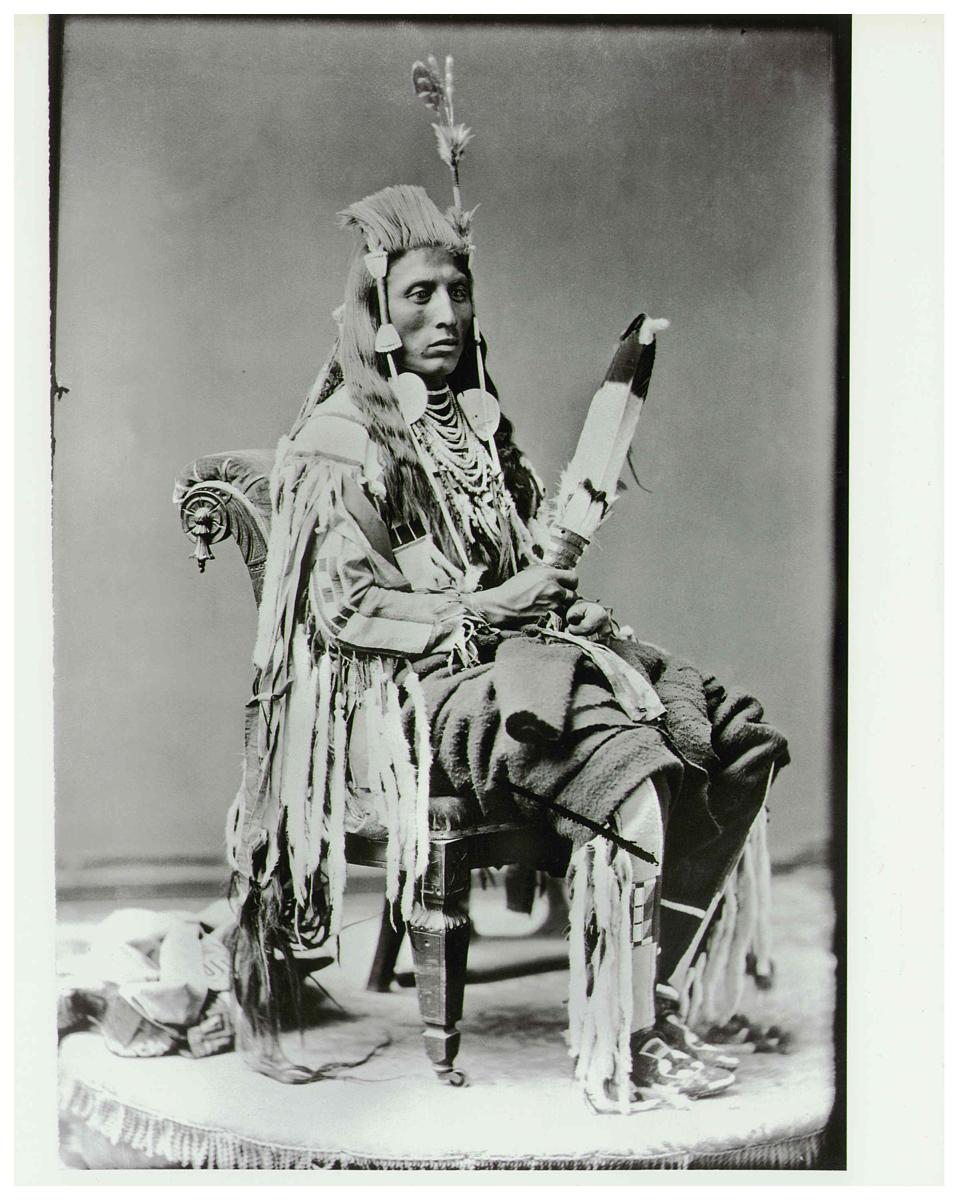

In an article published in Montana The Magazine of Western History (2001), Bill Holm makes a profoundly compelling argument that a photograph, taken by F. Jay Haynes in 1883, of Curley, wearing the White Swan robe, confirms that it belonged to the Montana Historical Society, stated in a 1995 communique that it was unclear "whether the robe in the photograph belonged to Curley or if it was one that Haynes used as a prop for studio portraits." When compared, however, the color patterns are tographs published in this article, the distortion of color varies does not prevent one from primary motifs, ues in the portrait by Haynes is almost entirely consistent with technological limitations that plagued earlier photographic processes and provides, perhaps, the single most compelling visual attribution this particular robe to Aspaalooke artisans. Plateau beadworkers, on the other hand, employed a wider range of colors on figure backgrounds, and rarely combined outlines with borders. Artists from the contiguous Plains region, such as the Blackfoot, commonly featured wider color schemes indicate that the White Swan blanket strip is, almost most certainly, of Crow origin.

The White Swan robe possesses exceptional historic and artistic significance, but those qualities were not widely recognized outside of Montana before 1995, when the Montana Historical Society graciously agreed to loan this artifact for a major exhibition (“With Pride They Made These: Tribal Styles in Plains Indian Art”) that I co-curated at the Frank H. McClung Museum, University of Tennessee. During the following year, I wrote my M.A. thesis on the White Swan robe. This masterpiece was featured again in the Montana Historical Society’s 2018 online exhibition, “Appropriate, Curious, & Rare: Montana History Object by Object.” In a related competition, dubbed “Montana Madness,” the White Swan robe was ultimately selected by participants as one of the four objects most representative of Montana history. It remains a fitting tribute to Montana’s nineteenth-century Plains Indian artists, most of whom are not credited in the historical record.

Leave a Comment Here