Lost Montana

In the early morning of July 9th 2019, a line of strong thunderstorms raced across the southern Canadian plains headed for the northeastern corner of Montana. This part of the state is not unaccustomed to seeing strong storms, but this storm packed a powerful punch. By the time it crossed into Sheridan County. its winds were gusting more than 40 miles per hour. Rain was also coming down hard and punishing everything in its path.

Moments after crossing the border into Montana, it hit a small place on the map called Dooley. The only building still standing in Dooley was the Rock Valley Lutheran Church. Made of only wood back in 1915, the church had not seen a service or a congregation since the 1940s. It was built at a time when steam locomotives still roamed the prairie. And like many small rural churches, the Dooley Church, as it was often called, once embodied the hopes and dreams of the settlers who opened the west.

Much of the church’s roof was missing. And though the steeple still stood, the building developed a bit of lean over the past few years. Anyone who saw it knew its days were numbered. All it needed was a gentle push and it would topple. But on that warm day in July, the Dooley Church got a lot more than that.

No one saw it come down. Dooley is, after all, surrounded by little more than wheat fields and a few lonely old farm buildings. The Dooley Church, was mostly forgotten by everyone except the residents of Sheridan County and a handful of photographers who travel across the country to photograph old, abandoned buildings.

Photos by Todd Klassy

The Dooley Church was quintessential Montana. It stood tall and it stood strong for over 100 years. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1993, but without the funds or the care to preserve it, it weakened over time. Its clean architectural lines and weathered wooden exterior made it hauntingly beautiful. Those who saw it firsthand are fortunate. And those who did not will never know what they lost.

Dr. Verlaine McDonald grew up in these parts. She knows the area well and has written a handful of books about the history of this region. Now days she is Professor of Communication at Berea College in Kentucky. She knew the church had fallen and said it was a real loss.

“There’s definitely a sense of a void when one loses these rich landmarks that your grandparents maybe built,” she said. “An entire community might build these structures together, like an Amish barn raising. And as towns started popping up in the west, one of the first things they would do is build a place to worship.”

But McDonald said people in the rural parts, like Sheridan County, may be accustomed to these losses because they have seen farmhouses, barns and homesteader shacks deteriorate over time. But she said, it doesn’t mean there isn’t a real sense of loss.

“For those who remember someone who was baptized or married in the church, or played in the tall grass around it, or heard stories from grandparents about it, it is still a huge loss,” she said.

Photos by Todd Klassy

Unfortunately, the fate of the Dooley Church is not all that rare these days. Across the state there are landmarks and historical markers of Montana’s past that are disappearing every year. Weather, vandalism, and neglect combine to damage or destroy important historical and cultural sites. Others are erased because they stand in the way of progress. Many more vanish simply because of the lack of resources to save them.

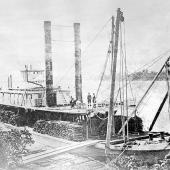

Half a state away in Hobson, Montana, two more old buildings almost met the same fate as the Dooley Church. Two big old red grain elevators (there once was a third) have stood at the entrance to Hobson for more than a century. The railroad deemed them dangerous and too much of a liability. They simply could not afford to keep them standing any longer. So, they told the community they were going to tear them down. A sort of architectural euthanasia. The people of Hobson had grown fond of these tall twin towers, which stood guard over the community since 1910. They were not only part of Hobson’s skyline, they were Hobson’s skyline.

Old churches, and schoolhouse, and barns. Old brick buildings that were once a mercantile in some small town, tipi rings, and homesteads. They are all a testament to Montana’s past. But every year more and more of them are lost forever.

Many old wooden grain elevators, like the ones in Hobson, once carpeted the countryside throughout the state. Then larger, bigger, and better grain elevators began to replace them. With the loss of train stops along many routes, the fate for many was all but sealed. But in the rural parts of Montana, even long after these structures had served their intended purpose, they continued to stand over the plains and scrape the sky. Few who lived in these parts ever wanted to see them go.

Photos by Todd Klassy

Luckily for all Montanans, the good people of Hobson decided they wanted to save their grain elevators. The railroad gave the people of the Hobson six months to come up with a solid plan to preserve the structures and bring them up to code, raise the necessary funds to do so, and enter into a property lease with BNSF Railway. And without a moment to spare, the community raised the necessary funds, sealed off the entrances to the elevators, made the necessary repairs, and finalized a lease with the railroad. And hopefully the elevators will stand another hundred years.

Other grain elevators in the state, however, have been less fortunate. Elevators in Culbertson, Laurel, Lothair, Suffolk, Belt, Sacco, Clyde Park, Ryegate, and many other places have been torn down and lost forever in recent years. These cathedrals on the prairies are historical markers. For some they are the tallest buildings they will ever see.

Architecture, regardless of how simple or utilitarian, is a poignant expression of human progress and the passage of time. It documents the struggle of pioneers and settlers and the people who built Montana on the sweat of their brow. Thankfully there are those who work every day to try to preserve our historical and cultural sites.

Since it began in 1966, more than 95,000 properties across America have been added to the National Register of Historic Places. It is the official catalog of historic properties in America. Created by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places was intended to identify, evaluate, and protect America’s historic and archeological treasures.

Photos by Todd Klassy

In Montana, there are over 1,100 listings in all 56 counties on the Register. Flathead County has the most with 147, while Garfield and Teton County have just one each. The list includes many exemplary forms of architecture, including such landmarks as the Cathedral of Saint Helena in Helena, the Conrad Mansion in Kalispell, and Hotel Metlen in Dillon. The list also includes historic locations, such as the Bannack Historic District, Little Bighorn Battlefield, Pompey’s Pillar, and various buffalo jumps and native American Indian heritage sites. And while there are many other buildings and historically significant sites in Montana already on the list, many never make the list, increasing the chances that those not on the list will vanish forever.

Peter Brown is Montana’s State Historic Preservation Officer. He is responsible for helping to identify historic properties, review nominations for new properties, and survey them. He has worked in the field of historic preservation for more than 20 years and takes great pride in helping to preserve Montana’s historic landmarks and properties.

“I have always been interested in history and my attention naturally gravitated to old places,” Brown said. “My earliest memory is of a fort that was rebuilt and preserved near my hometown. I was amazed at how things used to be, and I always spent a lot of time on my bike checking out old buildings and historic properties.”

Asked why he thought historic properties eventually disappear, Brown said, “It boils down to priorities. First, you need the financial means to maintain a building that has no obvious use. Combined with a low population in the state, finding a use for many of these old buildings is next to impossible unless they are used for storage.”

Photos by Todd Klassy

Brown said you also need more than just money to save a building, too. “If you don’t have local interest in the community, money often isn’t enough to save a historic landmark,” Brown said. “You need people interested in putting that money to use, too.”

Just being added to the National Register of Historic Places also doesn’t guarantee preservation either. And interestingly, despite what some may think, “There are no requirements people must do or anything special to maintain a historical property in the Register. The Register is an honor roll of historically significant places worthy of preservation, but there is nothing that prevents the owner of the property from making changes to the building or changing it’s use,” he said. “Unless of course a local government has its own rules and requirements. Otherwise, there are no rules or requirements once a building is added to the National Register of Historic Places.”

Other than Mother Nature, Brown added that there are other reasons why historic landmarks disappear. In downtown Bozeman, for example, it may be development pressure. In the more rural parts, changes in farming make certain buildings obsolete. Barns, for example, were once designed to filled with small square bales of hay. Large round bales have replaced them, however, and they are stored outside, thus making it easier for the building to sag and become a victim to the elements over time. Consolidation of farming and ranching properties also has an impact. And it seldom the result of deliberate neglect. Especially in rural Montana, there’s only so many funds to go around.

Though the State Historical Preservation Officer conducts some education and outreach, his time and funding is limited. Other organizations must fill the gap and help really spread the word. One of the most active and important groups in the state of Montana is Preserve Montana, a group that strives to save and protect Montana’s historic places, traditional landscapes, and cultural heritage.

It stood for over 100 years before it was torn down in 2014.

Photos by Todd Klassy

Chere Jiusto is the Executive Director for Preserve Montana, and she said their group is actively helping to catalog the history of the state and find the resources necessary to preserve the most important and most endangered sites among us.

“A lot of work we have been doing recently is trying to look at the baseline of what’s out there, what iconic buildings best represent the history of Montana that everybody shares, and the biggest threats to them,” Jiusto said.

“There are many places that aren’t listed (on the Register) that could be,” she said. “For example, we just wrapped up a survey across the state of every standing schoolhouse. We ended up with about 1,000 historical schoolhouses. Only a few of those are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. And several of them could be.”

Jiusto said sometimes a historical landmark or building isn’t listed but is still important to the community.

“They still tell the story of how that community came to be and shaped it over time. In those cases, we will try to find solutions to keep them intact.”

Montana is a relatively young state, so some may think its history is not as important as the history in other places. But our landmarks and places are touchstones. They tell the story of our state and its people. Montana, like all places, will continue to evolve. Change is the one thing that is constant, but our landmarks and historic places help mark the time. With so many disappearing, though, it begs the question…which ones will remain when all the others have been torn down?

Photos by Todd Klassy

- Reply

Permalink