When Steamboats Ruled Montana's Waters

Virtually from the moment that Lewis and Clark proclaimed the Three Forks of the Missouri as “richer in beaver and otter than any country on earth,” the first generation of mountain men targeted that area as the holy grail of beaver trapping grounds. Unfortunately, their blatant disregard for Blackfeet territorial claims sowed the seeds for 25 years of bloody conflict. Despite such entrenched resistance, the American Fur Company achieved dominance in that operational theater only five years after Kenneth McKenzie (1797-1861) assumed directorship of the AFC’s Upper Missouri Outfit in 1827.

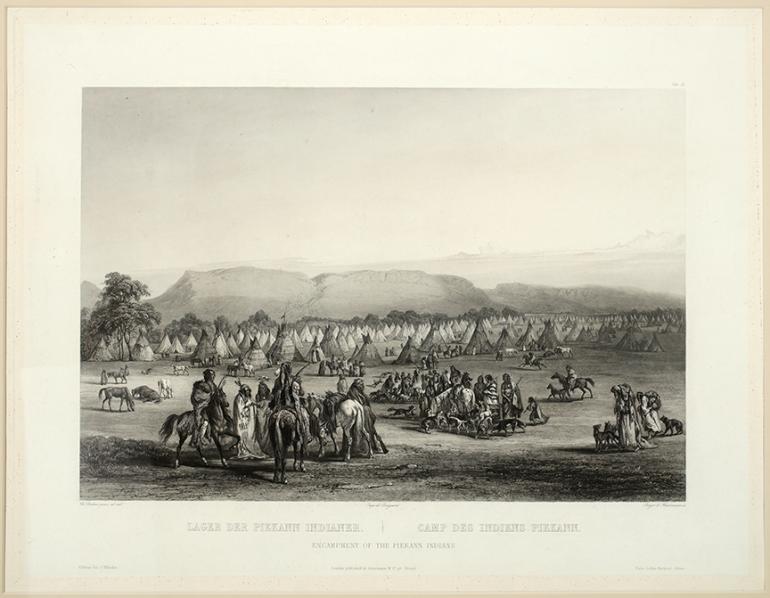

A breakthrough in relations with the Blackfeet occurred shortly after Fort Union, the region’s flagship post, was completed in 1830. McKenzie dispatched Jacques Berger, who had 21 years of experience in the Canadian fur trade, to contact and, hopefully, persuade Blackfeet leaders to entertain offers of commerce with the AFC. Berger’s familiarity to the Blackfeet and his fluency in their language ultimately contributed to successful negotiations. In the spring of 1831, almost 100 Piikani (Piegan), Siksika (Blackfeet proper) and Kainah (Blood) chiefs and leading warriors accompanied Berger and his party to Fort Union, where they formally agreed to construction of the first American trading post in Blackfoot country. When Fort Piegan became operational later that year, the Blackfoot blockade of the upper Missouri fur trade had officially ended.

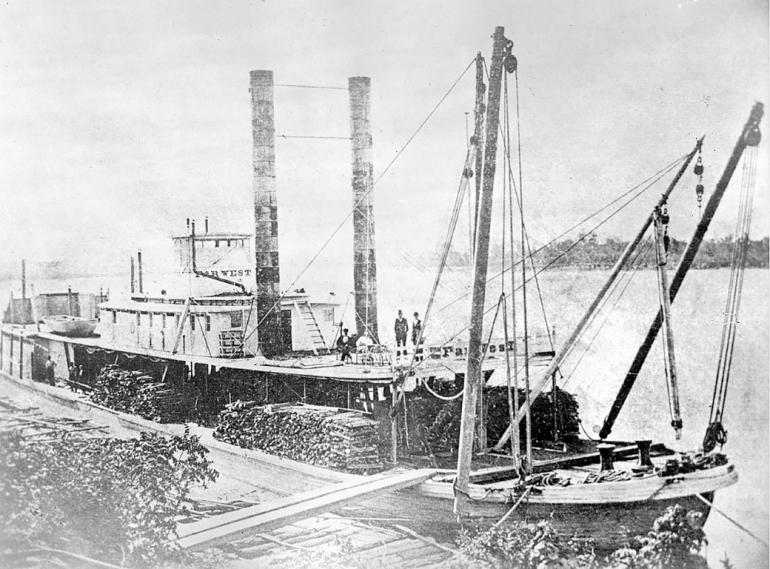

McKenzie also formulated a strategy to revolutionize the industry’s transportation network by introducing steamboat traffic to the upper Missouri. With the approval of Pierre Chouteau, Jr., contractual arrangements were agreed upon for construction of a boat in Louisville, Kentucky, which was scheduled for delivery to St. Louis by April 1, 1831. Christened the Yellow Stone, its voyage in 1832 was, according to Hiram Martin Chittenden, a “landmark in the history of the West. It demonstrated the [feasibility] of navigating the Missouri by steam as far as the mouth of the Yellowstone, with a strong probability that boats could go on to the Blackfoot country.” Fort Union was the final destination for steamboat traffic until 1859, when access was extended upriver to Fort Benton.

As a mode of transportation, steamboats compressed time and distance, compared to the laborious transits previously made by keelboats. Ramsey Crooks astutely conveyed the importance of this development in a letter to Chouteau, wherein he congratulated the latter on having “brought the Falls of the Missouri as near comparatively as the River Platte was in my younger days.” Steamboats’ ability to transport massive amounts of cargo enabled the American Fur Company to adroitly pivot from its emphasis on beaver pelts to the burgeoning bison robe trade. By the early 1830s, beaver populations in many Rocky Mountain trapping grounds were already depleted. Increased availability of silk from China and a growing preference for its use on men’s hats sharply suppressed market demand and, thus, the price paid for plews. By the end of that decade, it simply was no longer profitable to trap beaver.

The bulk and weight of bison robes, on the other hand, precluded development of a significant market prior to the use of steamboats as cargo vessels on the upper Missouri. In 1812, for example, the American Fur Company acquired only 12,000 robes from the equestrian tribes. Twenty years later, the Yellow Stone picked up 7,200 robes at Fort Union alone, and trade in that commodity increased quickly thereafter.

Data from Fort McKenzie, the principal AFC post in Blackfoot country from 1834-44, clearly illustrates this trajectory. Despite severe population losses incurred during the smallpox epidemic of 1837-38, Blackfoot trade at Fort McKenzie increased from approximately 3,000 robes in 1835 to 21,000 in 1841, which made it the most productive fort in the interior West. In accordance with Kenneth McKenzie’s entrepreneurial vision, the American Fur Company had, in short order, wrested the coveted Piikani trade from their Canadian competitors.

The best available evidence indicates that traffic from AFC posts on the upper Missouri averaged 25,375 robes from 1828 to 1834, rose markedly to 67,000 in 1840, and peaked in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Reliable sources cite the following figures for annual trade during the latter period: 110,000 robes in 1847-49 and 100,000 for 1850. After reaching its high-water mark, the AFC’s Upper Missouri Outfit purchased 88,927 bison robes in 1853, 75,000 robes in 1857 and, based on Pierre Chouteau’s estimate, only 50,000 robes in 1859.

Sadly, data from individual posts allow us to chronicle the surprisingly swift westward contraction of the bison range. Traders at Fort Pierre, which serviced the Sioux, collected 75,000 robes in 1849, “over two-thirds of the robes produced in the northern plains that year.” Only eight years later, trade at that post plummeted to 19,000 robes. Such rapid depletion of game populations fueled the ongoing westward migration of the Lakota and an escalation of intertribal warfare.

The advent of steamboat traffic on the upper Missouri dramatically improved the operational efficiency of the AFC’s transportation network and facilitated regional access for a host of dignitaries, explorers, missionaries, and government agents. Adhering to the precedent established by his father, who aided Lewis and Clark in preparations for the Corps of Discovery, Pierre Chouteau, Jr., supported and subsidized the advancement of knowledge, most notably in anthropology, geology, and natural science. Consequently, from 1830 until the renowned missionary Pierre Jean De Smet made his final visit to the area in 1863, Fort Union and other AFC posts on the upper Missouri provided lodging and research assistance to a litany of artists, ethnologists, and scholars in various academic disciplines.

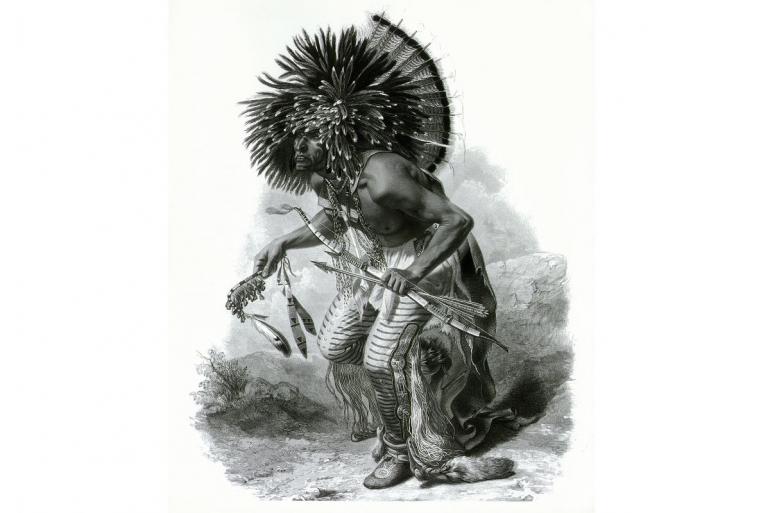

Beneficiaries of AFC generosity included artists George Catlin (1832), Karl Bodmer (1833-34), and Rudolph Friederich Kurz (1851-52). Duke Friedrich Paul Wilhelm, from Württemberg, Germany, was the first dignitary to visit Fort Union in 1830, followed by fellow naturalists Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied (1833-34), and John James Audubon (1843). In 1862, pioneering anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan, often described as the “father of modern ethnology,” became the last scientist to travel by steamboat to Fort Union.

Expeditions by Catlin and Prince Maximilian are particularly noteworthy. When they ventured into this area, landscapes traversed by the upper Missouri remained virtually pristine, despite thousands of years of human occupation. The timing of their fieldwork also was fortuitous; it enabled them to compile a treasure trove of ethnographic data less than five years before the catastrophic smallpox epidemic of 1837-38. Furthermore, their experiences underscore the vital but often neglected role that fur traders played as cultural liaisons and proto-ethnologists, which contributed immensely to the eventual success of Catlin, Maximilian and subsequent researchers.

A passenger on the Yellow Stone’s inaugural voyage to Fort Union, George Catlin conducted a whirlwind, 86-day ethnographic tour of the upper Missouri during the summer of 1832. He produced an impressive written and pictorial record, but anthropologist John C. Ewers noted that it was “patently impossible for [Catlin] to gain more than a superficial familiarity” with the tribes that he visited. Therefore, Catlin relied extensively on fur traders at AFC posts for data that he incorporated in his journal. Catlin’s artwork exhibits a comparable degree of superficiality, one in which detail was often sacrificed, out of necessity, on the altar of expediency. Ewers estimates that Catlin created more than 135 paintings, most of which were portraits, over the course of his trip.

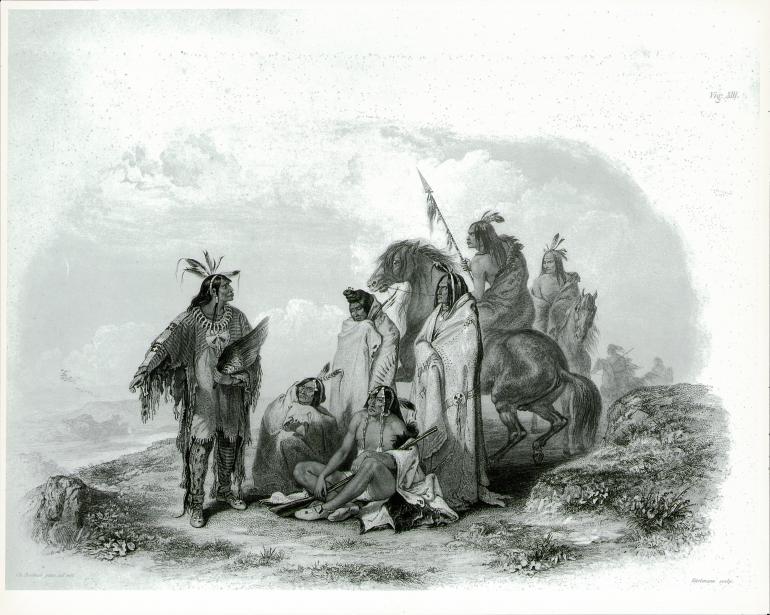

Maximilian and Bodmer, however, devoted almost a year to ethnographic research among the Upper Missouri tribes. The most productive phase was spent among the Mandans and Hidatsas who lived near Fort Clark, where expeditionary members wintered from November 8, 1833 until April 18, 1834. Publication of their work provided an appropriate capstone to the most important ethnographic expedition conducted in America during the nineteenth century. Karl Bodmer crafted its most enduring legacy, one consisting of nearly 400 watercolors and sketches, of which 81 first appeared in an aquatint atlas for the English edition of Maximilian’s Travels in the Interior of North America (1843).

Bodmer’s Mandan and Hidatsa portraits, examples of which illustrate this article, constitute the very finest of an extraordinary body of work. Indeed, subsequent observers consistently praised the exquisite detail of Bodmer’s artistry. His aquatints, according to author Robert Moore, are “the most accurate works of art ever made of American Indians during the nineteenth century.” Historians William Goetzmann and Barton Barbour conclude similarly that “No artist ever duplicated the ethnographic detail captured in Bodmer’s Indian portraiture,” nor would such precision be replicated until the photographic camera became available in the West.

However, the ethnographic and artistic records compiled at Fort Clark by Catlin, Maximilian and Bodmer would have been immeasurably impoverished without the assistance of James Kipp, a fur trader who lived among the Mandans from 1822 to 1835 and was, allegedly, the first white man to learn their language. His rapport with the Mandan people enabled Kipp to obtain permission for Catlin to attend the Okipa, an elaborate religious ceremony that closely resembled the Sun Dance, with its emphasis on world renewal and rites of self-torture. Kipp’s presence throughout the four day ceremony and his interpretation of its constituent rituals provided cultural insights that greatly informed Catlin’s written account.

John James Audubon benefitted similarly from the expertise of AFC traders James Kipp, Edwin Denig and Alexander Culbertson. The two months that Audu - bon and his party spent at Fort Union in 1843 were devoted primarily to field research and specimen acquisition for his last great project, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (1845-48). Interestingly, their experience also illustrates the role that fur traders occasionally played as a curatorial conduit through which visiting dignitaries received rare, early examples of Plains Indian material culture, many of which were ultimately donated to various museums. For example, Culbertson and his Blood Indian wife, Natoyist-Siksi - na’ (Holy Snake), gave Audubon a classic Blackfoot dress, one heavily embroidered with blue and white pony beads, which is currently housed in the American Museum of Natural History.

Edward Harris, an amateur ornithologist and close friend of Audubon, also assembled a small but significant collection of Plains Indian artifacts at Fort Union. Entrusted to the Alabama Department of Archives and History, its showpiece is a spectacular quilled and hair-fringed war shirt. Culbertson informed Harris that this shirt belonged to “a chief called by the French Le Soulier de femme or Woman’s Moccassin,” a prominent Blood war leader whom Catlin met (and depicted) eleven years earlier but identified, at that time, as Eagle Ribs.

In the final analysis, Kenneth McKenzie’s ardent advocacy for use of steamboats on the upper Missouri revolutionized the American Fur Company’s transportation network, which enabled it to establish dominance in that operational theater, wrest the lucrative Piikani trade from Canadian competitors, and transition seamlessly to the burgeoning bison robe trade. Almost from its inception, Pierre Chouteau, Jr. utilized this innovation to support and subsidize artists, as well as fledgling scientific disciplines, such as anthropology and geology. The works of Catlin, Maximilian, Bodmer, Audubon and Kurz are notable byproducts of this policy.

Nevertheless, the impact of steamboat traffic on the upper Missouri was not entirely benign. During the first half of the nineteenth century, consumption of firewood by steamboats was, according to environmental historian Andrew Isenberg, “probably the [main] cause of riparian deforestation in the United States.” A phenomenon that was especially problematic on the sparsely timbered Northern Plains, historian Donald Jackson contextualizes its detrimental effect superbly. Jackson estimates that, on its 1833 voyage to Fort Pierre and back, the Yellow Stone burned “the equivalent of 1,700 oak trees that might have been growing for half a century.” Finally, and most tragically, the steamer St. Peter’s carried an invisible and insidious cargo upstream during the spring of 1837; it spread the smallpox virus from Fort Clark to Fort Union, thus unleashing the benchmark epidemic in Montana history.

Rottentail (?) Crow, October 26, 1851. Portrait by Rudolph Friederich Kurz, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Negative no. 2856-93.

Leave a Comment Here