When Death Rode a Pale Horse

The Smallpox Epidemics of 1781–1782 and 1837–1838 in Montana and the Upper Missouri

The onset of epidemic disease has long evoked a primordial fear in the hearts of people, particularly when a novel pathogen, one for which nobody possesses immunity, is introduced to “virgin-soil” populations. Fortunately, Montana has never been subjected to a pandemic as devastating as the Black Death, a virgin-soil manifestation of bubonic plague, which ravaged Europe from 1346 to 1353.

Most historians and epidemiologists estimate that the Black Death killed approximately 30–50% of Europe's pre-plague population. However, Ole Benedictow, the author of The Black Death: The Greatest Catastrophe Ever, presents a painstakingly crafted argument that fatalities were much higher, some 60% of the population. See https://www.historytoday.com/archive/black-death-greatest-catastrophe-ever.

Disease outbreaks in Montana are dwarfed by this 14th-century pestilence, primarily because of enormous differences in population. Nevertheless, tribes indigenous to Montana and the northern plains were afflicted by two virgin-soil epidemics that resulted in mortality rates equal to, if not greater than, those caused by the Black Death. Consequently, the smallpox epidemics of 1781–1782 and 1837–1838 remain unsurpassed for their lethality in Montana epidemiological history.

In Pox Americana, Elizabeth Fenn traces the emergence of a hyper-virulent and deadly strain of the virus, variola, during the three centuries that preceded the pan-Plains outbreak of smallpox in 1781. Florence, Italy, which had been utterly decimated by the Black Death, recorded a total of only 84 deaths from three smallpox epidemics that transpired between 1424 and 1458. A mid-17th-century outbreak in London resulted similarly in a mortality rate of seven percent. Subsequent outbreaks in Boston and Scotland, which occurred, respectively, in 1792 and 1787, claimed the lives of approximately 30% of their victims. A virgin-soil epidemic that struck an isolated village on the Japanese island of Hachijo-Jima a few years later provides important context for hypothesizing minimal mortality rates among the Upper Missouri tribes in 1781. “Of the 86 percent of villagers infected,” Fenn states that “some 38 percent died.”

This invisible assassin crossed the Rio Grande by late 1780 or early 1781, when it infected the Comanches, most probably through contact with Spanish traders in Texas and New Mexico. Far to the north, traders reported its presence among the Assiniboines and Crees in October 1781. As historian Theodore Binnema observed, “Never before had so large a portion of the population of the plains faced such a calamity.”

Once they contracted the disease, the Shoshones played a disproportionate role in its dissemination to the Upper Missouri tribes. The Shoshones' wealth in horses positioned them as prominent brokers in intertribal trade, but it also made them frequent targets for enemy raiding parties. Young Man, a Piikáni (Piegan Blackfeet) warrior, recounted the ghastly consequences of one of these chance encounters to David Thompson, a fur trader. In a dawn attack, Young Man and his comrades slashed open the Shoshones’ tipis and were immediately “appalled with terror, [for] there was no one to fight with but the dead and dying, each a mass of corruption [sic].”

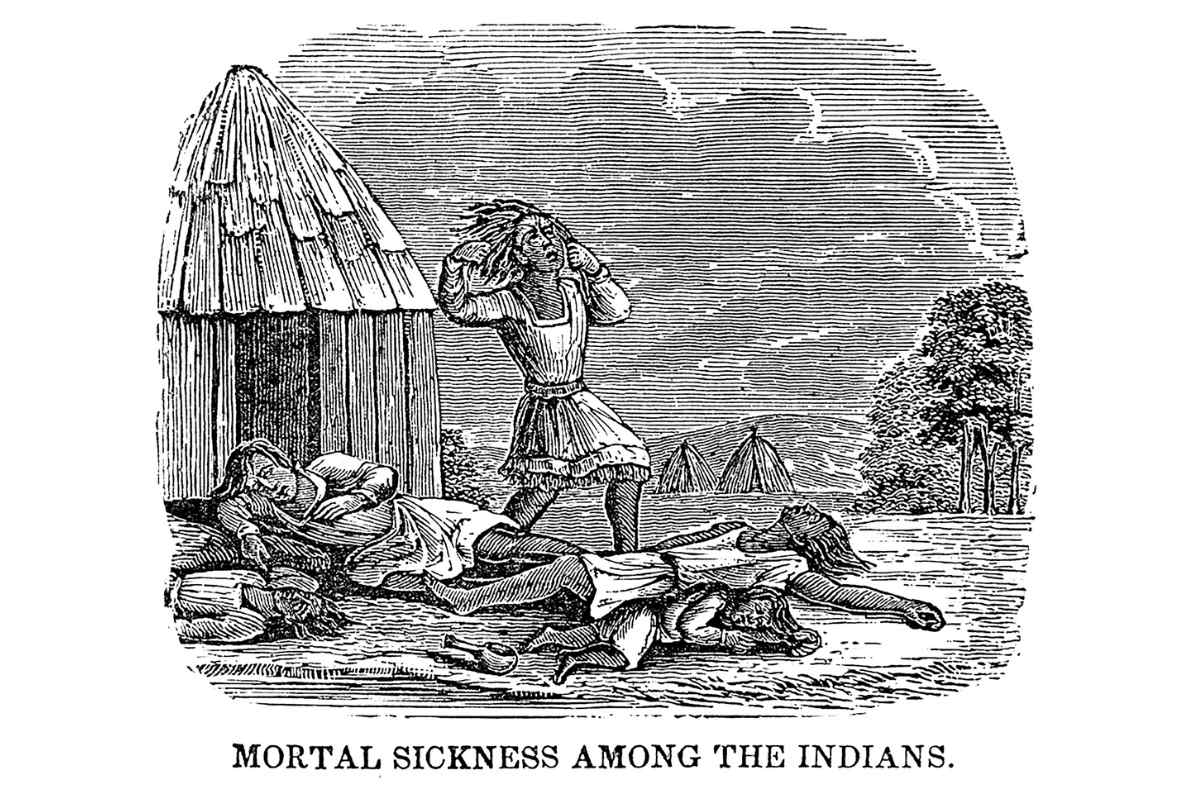

As members of afflicted tribes witnessed and personally experienced the symptomatic progression of smallpox, especially the horrifying disfigurement it caused, they became distraught. The latter phenomenon is most clearly illustrated by the graphic descriptions of suicide chronicled by fur traders during the epidemic of 1837–1838. The nature of the disease’s origin was also disturbing to Plains Indians, who had no comprehension of interpersonal disease transmission. As Young Man informed David Thompson, “We had no belief that one Man could give [the illness] to another, any more than a wounded Man could give his wound to another.”

According to eighteenth-century fur traders in Canada, the Northern Plains tribes suffered catastrophic losses during this pestilence. In a summary of their findings, Fenn states that “estimates of overall mortality among the Atsinas, Crees, Assiniboines, Chippewyans, and Blackfeet ranged from 50 to 98 percent.”

Without reliable, quantitative data to corroborate those assertions, Fenn calculated baseline (minimum) mortality estimates. Utilizing the best demographic data available for that period, Fenn assumed a mortality rate of 43 percent, a statistic based on analysis of 7,000 “unvaccinated smallpox cases in Madras, India, during the 1960s.” Acknowledging the limitations of her methodology and source materials, Fenn concludes that this epidemic killed at least 13,000 Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras, as well as 3,440 Crows, 3,583 Sioux, and 10,406 “Northern Plains Indians,” i.e., tribes that occupied territories located primarily or exclusively in Canada.

Sadly, the writings of Alexander Culbertson, Edwin Denig, Charles Larpenteur and Francis Chardon clearly indicate that several Upper Missouri tribes suffered mortality rates from the epidemic of 1837–1838 that correspond closely to figures cited by their Canadian predecessors. Indeed, fatalities would have been significantly higher if vaccination programs had not been selectively conducted. Denig, for example, states that the latter epidemic reduced the Assiniboines’ population from a pre-plague level of 1,000 lodges to 400, while emphasizing that “200 [of these] were saved by having been vaccinated in former years by the Hudson’s Bay Company.”

After Congress passed the Indian Vaccination Act of 1832, the U.S. government implemented a short-lived, limited-scale program to vaccinate indigenous peoples against smallpox. However, in a communiqué dated May 9, 1832, Secretary of War Lewis Cass informed Indian Agent John Dougherty that “no effort will be made to send a surgeon higher up the Missouri than the Mandans, and I think not higher than the Arikaras.” Consequently, Michael Trimble, an archaeologist and historical epidemiologist, concludes that the “Yankton, Yanktonai, and Teton [Sioux],” particularly bands that lived near Fort Pierre, were “disproportionately vaccinated. [In] terms of conferred immunity among the Plains tribes, they clearly were at an advantage during the 1837–1838 epidemic.”

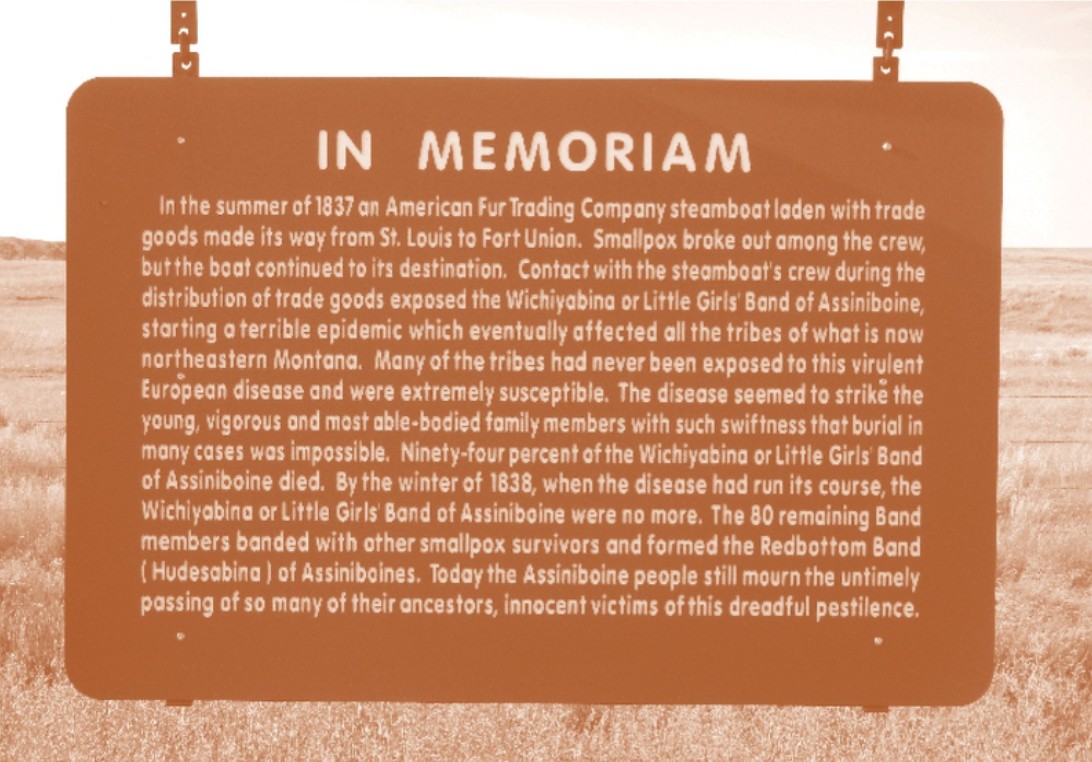

Variola spread swiftly in 1837 through contact with infected crew members and passengers of the St. Peter’s, a steamboat operated by the American Fur Company. During a provisioning tour from St. Louis to Fort Union, passengers who were still contagious disembarked at successive docking points, thereby delivering death to the doorsteps of tribe after tribe. As Trimble observed, smallpox infected virtually all indigenous peoples who lived “on or near the Missouri Trench [in only] seven weeks (first week of May to third week of June 1837).”

This outbreak exacted a horrifying toll from the Upper Missouri tribes, albeit one that cannot be quantified precisely. Specialists in Blackfeet ethnohistory commonly cite the research of James H. Bradley, who concluded that the three allied tribes suffered no “less than six thousand [fatalities], or about two-thirds of their whole number.” According to Denig, one Assiniboine band, which numbered “250 lodges or upwards of 1,000 souls” prior to the pox, was reduced to “thirty lodges or about 150 persons.”

The Mandans, however, experienced the most catastrophic losses. And their primary village of Mih-tutta-hang-kusch, located only a quarter of a mile from the viral repository of Fort Clark, became the epidemic’s epicenter. According to Chardon, the first death in a steady stream of Mandan fatalities occurred on July 14, 1837. Journal entries from August 10–22 corroborate a consistent pattern of 8 to 10 deaths per day at Mih-tutta-hang-kusch. On September 19, Chardon received a visitor from the little village (Ruptare), where he learned that only 14 residents were still alive. He emphasized that “the number of deaths [there] cannot be less than 800.” By the end of September, Chardon concluded that smallpox had slain “seven eighths of the Mandans and one half of the Rees [Arikara] Nations.”

Chardon’s journal is a uniquely valuable resource for tracking the progression of this outbreak, but it is not complete. By his own admission, he kept no record for the deaths of women and children. Consequently, estimates for the total number of Mandan survivors exhibit tremendous variability. The following figures may exclusively reflect the survivorship of adult males. Nevertheless, Indian Agent Joshua Pilcher informed William Clark in a letter dated February 27, 1838, that “thirty-one Mandans remained of an estimated population of sixteen hundred.” By contrast, Roy Meyer, author of The Village Indians of the Upper Missouri, estimates that 23 men, approximately 40 women, and perhaps 70 children survived.

Efforts to calculate the number of fatalities incurred collectively by the Upper Missouri tribes are complicated by the fact that rates of vaccination, infectivity, morbidity, and mortality varied significantly on both an intra- and intertribal basis. T. Hartley Crawford, who succeeded William Clark as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, advanced one of the most plausible estimates. Crawford reported that approximately 17,200 Assiniboines, Blackfeet, Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras had “sunk under the smallpox.” Pilcher offers a less precise but more visceral perspective, stating that the pox transformed the Upper Missouri into “one great grave yard.”

Why was this epidemic so deadly? For tribes like the Mandan, who had not been exposed to smallpox since 1781, only the elderly retained immunity. Interpreted through the lens of subsequent medical research, Denig’s account of the Assiniboine outbreak resurrects a highly suspicious culprit. According to this eyewitness, “two-thirds or more [of Assiniboine fatalities occurred] before any eruption [of pustules] appeared. This event was always accompanied by hemorrhages from the mouth and ears.”

Those characteristics were hallmarks of hemorrhagic smallpox, the rarest and most lethal manifestation of variola. If Denig had also referenced massive subcutaneous bleeding, which caused skin to assume a charred or blackened appearance, evidence for a diagnosis of hemorrhagic smallpox would be even stronger. In any event, let us pray that Montana is never targeted again by a pathogen as deadly as variola.

Leave a Comment Here