When the Journey Was Over: Pompey, Sacagawea and Patrick Gass's Lives After Making History

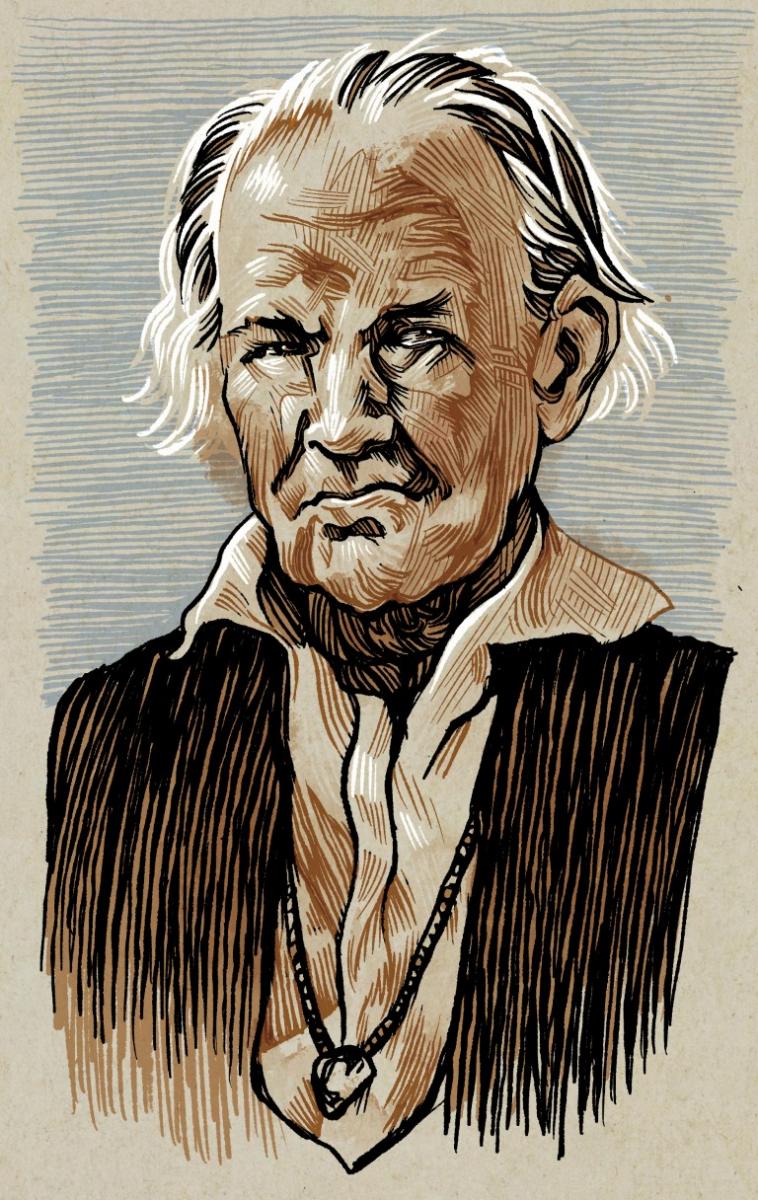

Patrick Gass (1771 – 1870)

On August 20th, 1804, Sergeant Charles Floyd made history as the only party member to die on the Lewis and Clark expedition. The group buried their friend on a bluff, but soon had to elect a new sergeant for the journey. Former Army Ranger Private Patrick Gass received the most votes and took to his new duties with ease. He was a skilled carpenter who oversaw the production of dugout canoes, winter encampments, and would be left in charge of the main group while the captains split into smaller parties to explore on the return trip.

All sergeants on the Corps of Discovery were required to keep a diary of the trip, and Gass obliged despite not having received a basic education until adulthood. Upon returning from the expedition, Patrick Gass approached schoolteacher David McKeehan to help prepare Gass’s journal to be published. Meriwether Lewis was struggling to write his own book during this time and exchanged heated letters with the publisher, which led to a brief public feud between Lewis and McKeehan.

Despite Lewis’s objections to what he considered an unauthorized recollection of the expedition’s events, “Journal of the Voyages and Travels of the Corps of Discovery” by Patrick Gass was picked up by at least six publishers and is still available through the University of Nebraska. Gass received 100 copies of the published work and retained the copyright, and the publishers kept most of the profits. Lack of funds from his creative endeavors did not deter Gass, as he continued to serve in the army after the expedition. While serving during the War of 1812, Gass worked for Daniel Boone on the construction of Fort Independence and fought in the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, during which a splinter of a falling tree blinded him in one eye, leading to an honorable discharge in 1815.

Gass worked a series of odd jobs for the rest of his life, until one prompted the then 60-year-old man to finally settle down. He had taken a carpentry job from a man named Hamilton, and soon fell in love with the man’s 20-year-old daughter, Maria Hamilton. The couple soon eloped and had six of seven children live to adulthood.

Patrick Gass is well known for being the longest-living member of the Corps of Discovery—sadly, he would also outlive his wife by 21 years. He often struggled to make ends meet later in life but was never one to complain. Known as a good husband, father, and friend, he passed away at age 99 and is buried near the top of the cemetery in Wellsburg, West Virginia, next to his wife.

Jean Baptiste "Pompey" Charbonneau (1805 – 1866)

Born to Sacagawea and Toussaint Charbonneau at Fort Mandan in 1805, Jean Baptiste, often called Pomp or Pompey by Captain Clark, unknowingly played one of the most important roles on the Lewis and Clark expedition. The presence of a mother and her young child among the group helped to persuade the Native people they would meet of the expedition’s peaceful intentions.

Clark’s interest in Jean Baptiste did not wane after the expedition ended, as the captain implored Charbonneau Sr. and Sacagawea to bring the boy to live with him. By 1807 Jean Baptiste’s parents obliged, and the family traveled to St. Louis. While under Clark’s care, Jean Baptiste learned from the captain’s extensive collection, essentially an in-house natural history museum. William Clark sent young Charbonneau to what is now St. Louis University High School at no small expense; it can be said that Clark most certainly had affection for the youngest expedition member.

After completing his education in St. Louis, Charbonneau got a job at a trading post. His ability to speak French connected him with Duke Friedrich Paul Wilhelm of the historical German territory Württemberg. The duke was impressed by then 18-year-old Charbonneau and invited him to return with the royal travelers to Europe, to which Jean Baptiste agreed. They set sail in late 1823, and Jean Baptiste would reside in the duke’s palace for approximately six years. He was already multilingual upon arriving in Europe, as he spoke multiple Native American languages, English, and French, yet he also took it upon himself to learn German and Spanish while abroad.

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau returned to St. Louis in 1829, with his linguistic skills proving to be quite helpful. He spent the next 11 years across the West while he worked the fur trade, guided a Scottish nobleman’s “lavish” expedition, and served as a guide again during the Mexican-American War. General Kearny instructed Charbonneau to join a march known as the Mormon Battalion, which traveled over 1,000 miles to construct the first wagon road to southern California and guide as many supply wagons as possible to Mission San Luis Rey de Francia near the sea. Only eight of the twenty-some wagons made it to their intended destination, but it was considered a success, and parts of the trail built by the battalion would become U.S. Route 66 and the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Some members of the battalion stayed at the Mission, and in November of 1847, Jean Baptiste was appointed alcalde (mayor) of the district. The job made him the only civilian authority in the region of 225 square miles, and he resigned less than a year later after being accused of bias when defending poor workers against the power of local landowners. Two months later, he appeared in Placer County, California, at the beginning of the state’s famous gold rush. There he mined for approximately 16 years at a site known as Secret Ravine and was very successful, as Charbonneau could afford the inflated cost of living near what is now Auburn, California. By 1860 he was working in the Orleans Hotel and had undoubtedly watched many fellow miners pass through town as the gold eventually ran out. He remained in the area for another six years, told the editor of the local newspaper that he “was about returning to familiar scenes,” and headed north to an unknown destination.

Historians speculate that Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was headed toward richer gold deposits, such as Bannack or Virginia City, or possibly the Owyhee Mountains of Oregon and Idaho. An accident occurred during a river crossing in southeastern Oregon, and somehow Charbonneau fell into the freezing water. He was taken to Inskip Station, where he was possibly given contaminated well water. He died there on May 16th, 1866. Charbonneau’s gravesite and memorials therein are recorded in the National Register of Historic Places and can be visited just outside the quiet town of Jordan Valley, Oregon.

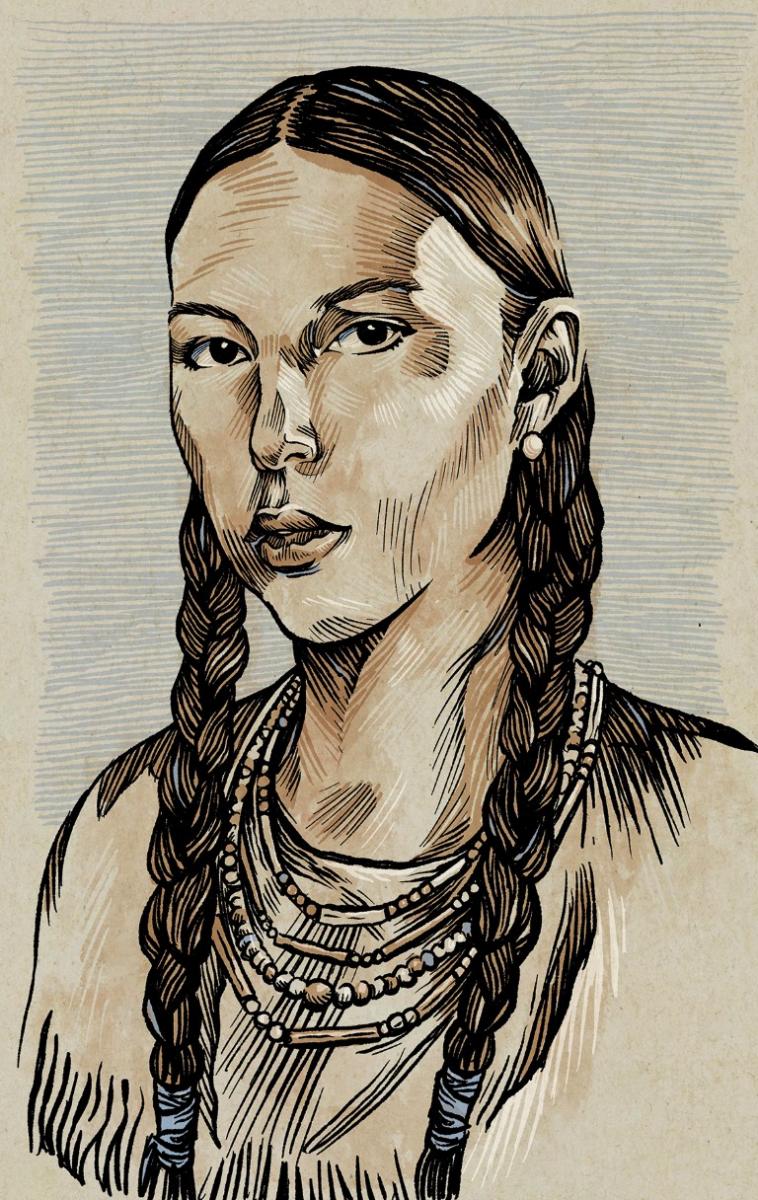

Sacagawea (1788 – 1812)

Sacagawea joined the Corps of Discovery in late 1804 and quickly proved to be nearly the most important person on the expedition. She was a crucial part of the interpretation process on many occasions, saved many essential supplies (including now-priceless journals and specimens) after a boat had tipped, and exercised a historical democratic vote concerning where to winter in the autumn of 1805.

William Clark’s insistence on housing and educating her son Jean Baptiste brought Sacagawea and her husband Toussaint Charbonneau to St. Louis in 1807 until the couple decided to return to the Mandan villages in 1809. Sacagawea made one more move back to St. Louis as she and Charbonneau tried to farm outside of the city, but departed for the final time in 1811 to find work at Fort Manuel Lisa. While at the fort, Sacagawea gave birth to a daughter named Lizette Charbonneau, who would later be adopted by William Clark. It is doubtful that Clark’s affection for Sacagawea and Charbonneau’s children was due to Toussaint. Both Lewis and Clark disliked Charbonneau, particularly his treatment of Sacagawea, and cataloged many such offenses in their journals. Sadly, poor Lizette may have died early in her childhood, going unmentioned thereafter in Clark’s journals.

Multiple accounts place Sacagawea and Charbonneau at Fort Manuel Lisa, and it is historically very likely that Sacagawea died there as well, as a traveler’s journal had noted that the young woman died after having recently given birth to a baby girl. The public was aware of her iconic stature , and many could not accept that she had passed away—Wyoming historian and suffragist Grace Hebard published her theory in 1933, suggesting that a different wife of Charbonneau had died; Sacagawea could have returned to her Shoshone people, and lived to be 100 years old. This seems unlikely, given the traveler’s journal mentioned above.

Shoshone oral legend maintains that Sacagawea did not die in 1812 but returned to her people to live until age 78, a possibility reinforced by the account of one Reverend John Roberts. He reported that he had buried an old Native woman and “people” claimed that she was, in fact, Sacagawea. It turns out the “people” he mentioned were specifically one person: Grace Hebard. In 1945, the reverend had confided to historian Blanche Shroer, “All I know is I buried an old Indian woman. The historian [Grace Hebard] told me she was Sacagawea.”

Although the whereabouts of her final resting place are now lost to time, nothing can diminish the incredible achievements, intelligence, and endurance of the only female member of the Corps of Discovery.

Leave a Comment Here