Nuts to the Noble Experiment: Montana’s Cussed Women Bootleggers

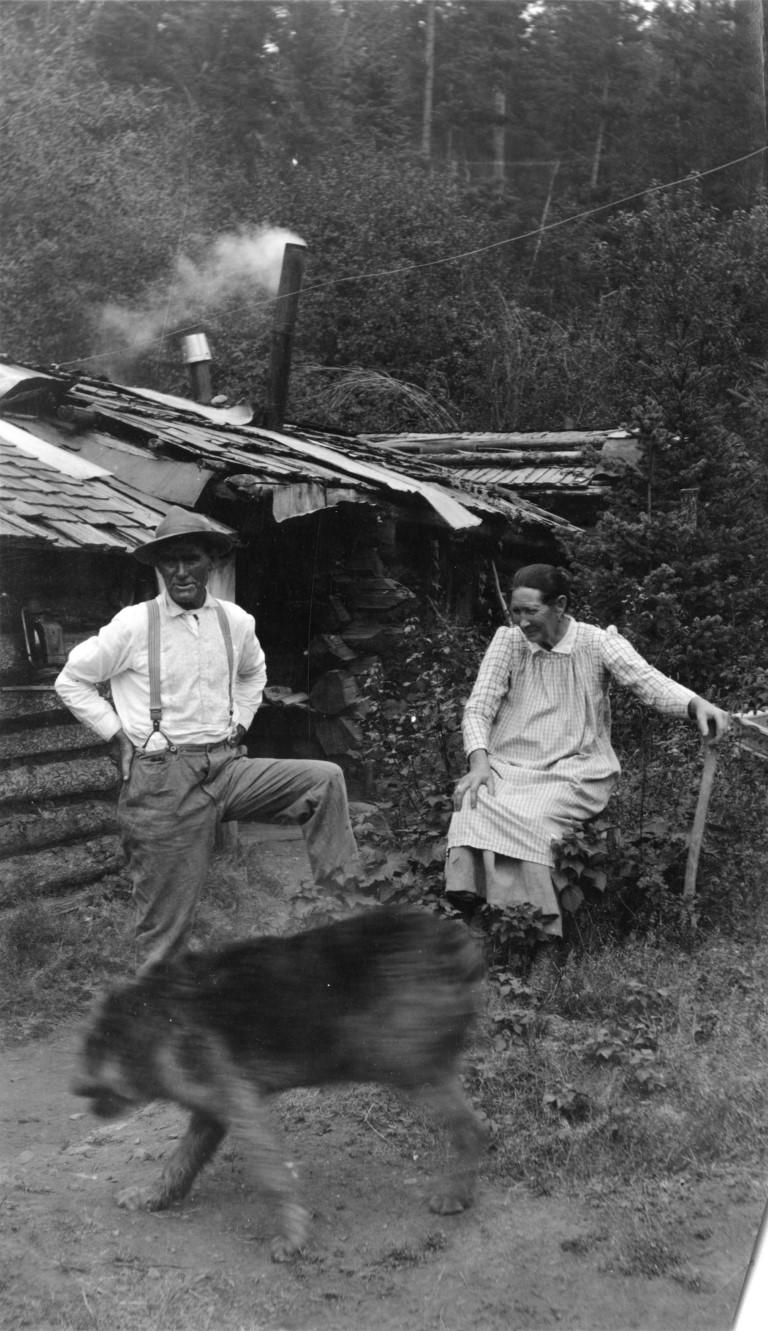

Dan and Josephine Doody in front of cabin (first cabin), south boundary of GNP, ca. 1910s Courtesy of the Glacier National Park Archives

Let us celebrate Montana’s most dogged women entrepreneurs—I’m not talking about women who homesteaded and proved up. No, I’m talking about women who saw a need and filled bottles and jugs to satisfy it.

They are the lady bootleggers and this is their story. But first, let’s take a look at the law they broke.

The 18th Amendment

Montana voted in Prohibition in 1916, in part due to the persuasiveness of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. They had whipped the voters up into a frenzy over the evils of alcohol. In late 1918, Prohibition under the 18th Amendment began in Montana—at least on paper. Saloons became soft drink parlors, ahem, until the law walked out the door and it was back to business as usual with moonshine and beer supplied by locals.

Those tasked with enforcing Prohibition expected to have a hard time in wide-open Montana—a state with abundant ingredients and lots of territory to cover. Dozens of bootleggers joined the fray, many of them women who made moonshine in their kitchens. Mind you, before Prohibition, respectable women weren’t allowed in saloons to drink. They drank, just not in public. Moms sent their children to the saloons’ back doors with pails in hand to fetch the brew. Ladies gathered to politely sip liquor in their parlors. Prohibition changed all that as they brewed beer, made wine, and distilled moonshine for themselves and for a wider audience.

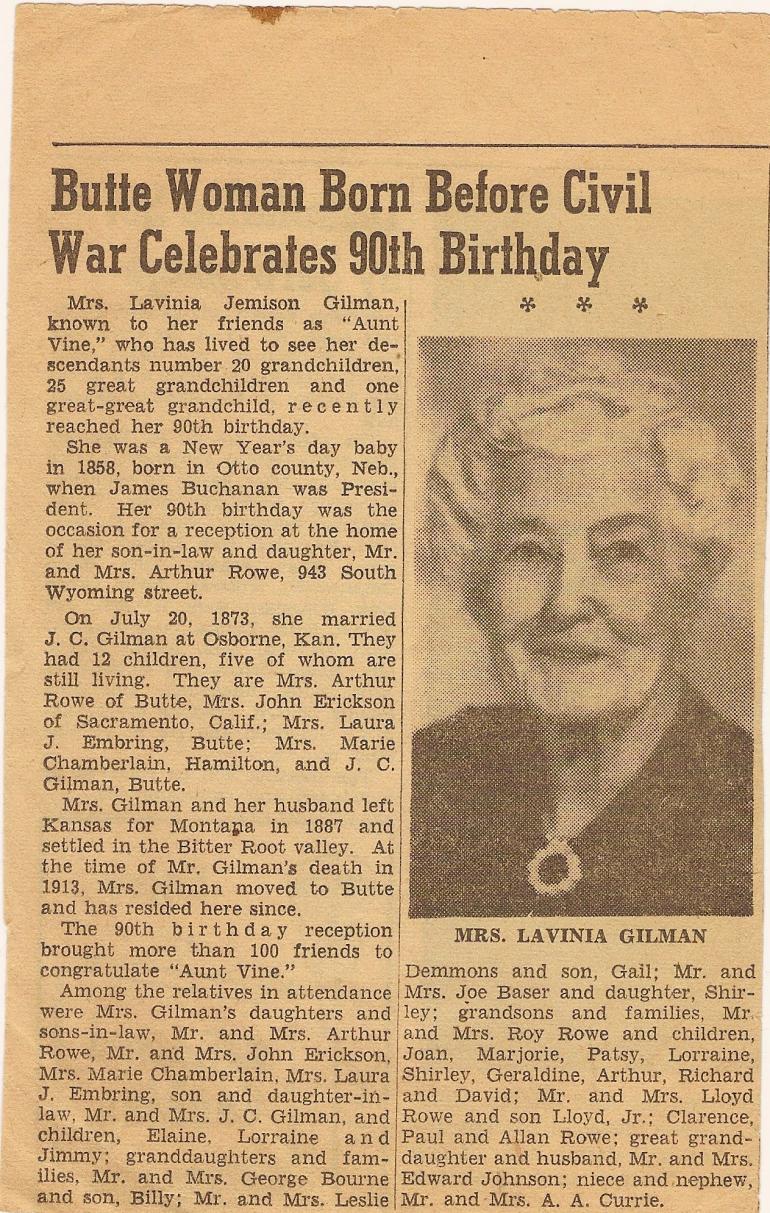

Is this THE Lavinia Gilman? Source: Montana Standard Newspaper

Silver Bow’s Businesswomen

Before Prohibition, Butte alone had more than 200 saloons. Silver Bow County was the most populous, and drinking was part of the culture. If you worked a risky job like so many of the men in Butte and Anaconda did, emerging from the mine shaft or smelter unscathed was cause for celebration.

It’s no surprise Butte and Anaconda had their share of bootleggers. Dozens were women. Few business opportunities existed for women in the early 1900s before this. They were mainly home-based—taking in boarders or doing laundry. Clever women dovetailed their existing businesses with bootlegging.

Some, like Nora Gallagher, had noble intentions. The Butte widow started bootlegging to outfit her five children for Easter. Mary Ann McGonigle combined bootlegging with her laundry business quite successfully and enlisted the help of her daughter to deliver clean clothes and hooch to her customers. Call it an apprenticeship, if you will.

And then there was a Butte grandma, Lavinia Gilman. She had petitioned to divorce her mean-drunk husband years before but jumped on the bootlegging bandwagon at the age of 80. When she got caught with a 300-gallon still, the judge believed it belonged to her son and summoned him to court. He didn’t show. Lavinia got off with a warning.

I found a birthday party notice in the 1948 Montana Standard society pages for Lavinia “Auntie Vine” Gillman. Was she the same woman? The birth years don’t jive, but maybe the judge was expected to be more sympathetic toward an 80-year-old than a 60- or 70-year-old. Her kind face and grandma status probably did the trick.

Josephine Doody with a catch of fish, in front of homestead cabin, Nyack. ca 1910s Courtesy of the Glacier National Park Archives

The Bootlegging Lady of Glacier Park

Of all the lady bootleggers, we know the most about Josephine Doody. John Fraley interviewed people Josephine knew and shared her story in his book, Wild River Pioneers: Adventures in the Middle Fork of the Flathead, Great Bear Wilderness, and Glacier National Park. And we have photos of her that are part of the Glacier National Park Archives.

Georgia-born Josephine Gaines traveled to Colorado. The story gets sketchy but suffice it to say, a dead man and Josephine’s smoking gun made her a fugitive. She fled to Montana, landing work in a dancehall in McCarthyville—a long-gone railroad town near Marias Pass. Dan Doody, a patron, fell in love with Josephine and stole her away via mule to his remote cabin near Glacier Park. She had no choice but to kick her opium habit and, in time, embraced their lifestyle—hunting, fishing, and guiding big game hunters. Josephine had a knack for making moonshine and evading the law.

Dan was friends with James J. Hill, a founder of the Great Northern Railroad that passed their homestead. Hill liked to fish and hunt with Dan and offered to have the train stop whenever Dan or Josephine needed a ride. This became a convenient way of getting their moonshine into rail workers’ hands, who distributed it to customers along the way. Railroad workers blew the train’s whistle, one toot for each quart. They had a booming business.

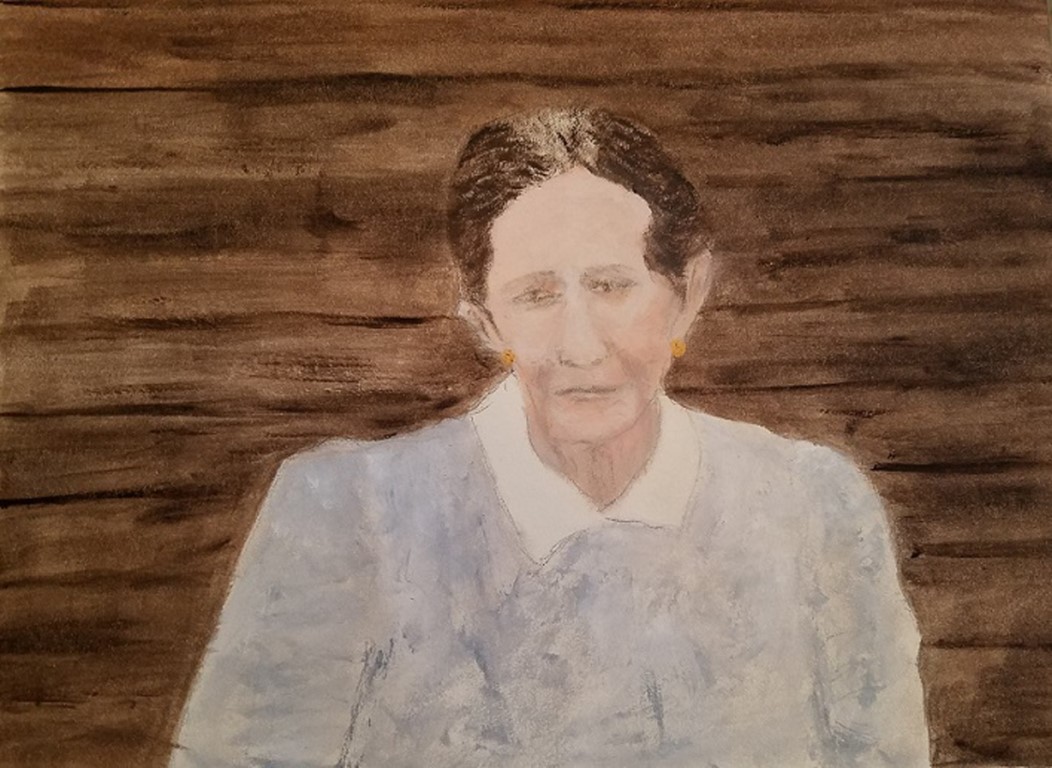

Josephine outlived Dan by 15 years and continued bootlegging. She proudly wore large gold nugget earrings that had stretched her earlobes like bananas, her friend Rick “Tiny” Powell said. The nugget earrings disappeared when she died, but her posthumous portrait by Roundup artist Jane Stanfel will always show her proudly wearing her treasured jewelry.

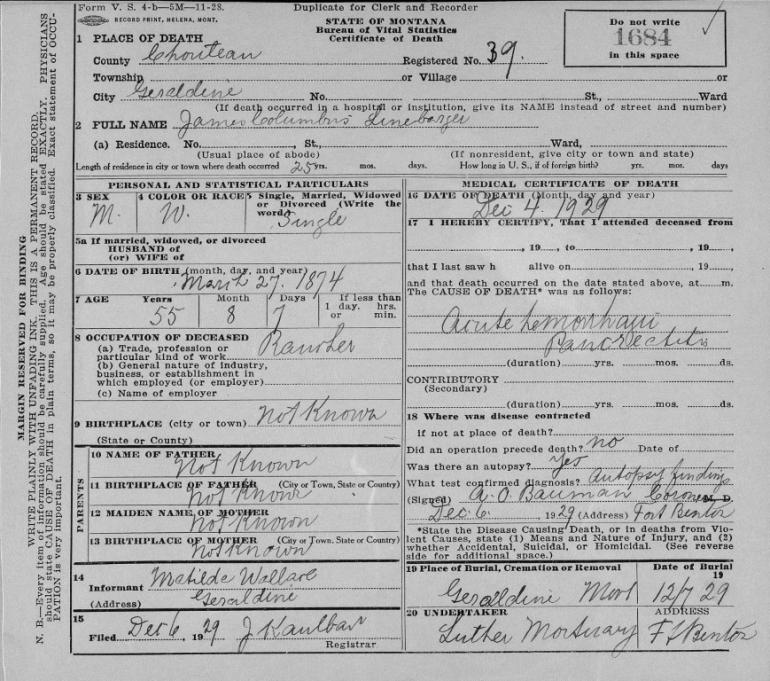

Linebarger Death Certificate Courtesy Ken Robison

Bertie’s Famous Moonshine

Stanfel also paid tribute to another prominent bootlegger, Bertie (Birdie) Brown. Stanfel, whose artwork graces walls in galleries, museums, and homes in the U.S. and abroad, painted Bertie’s homestead in Fergus County. Bertie moved to Montana in 1891 and became one of the first Black women to homestead independently in the state.

Her good nature, tidy “home speak” and famously good moonshine meant she had a steady stream of patrons. Rumor has it she plied Lewistown’s Officer Hill with liquor to let her off with just a warning to shut down her bootlegging business. After that warning, Bertie was dry cleaning with gasoline and cooking what would be her last batch of moonshine. It exploded, and she died from her burns.

A Two-Time Widow

Like Bertie, Mathilda Wallace was a homesteader. Her nature wasn’t as genial, though. Ken Robison, an author and historian at Fort Benton’s Overholser Historical Research Center, wrote about “Tillie.” Seems she married a man twice her age when she was just 17. She became a widow at 33. Bad luck? I’m not so sure.

She made her way to Montana with her daughter, homesteading near Square Butte. There she met James Linebarger. Locals suspected she poisoned this common-law husband, but she was never charged. Tillie hung on to the homestead by bootlegging until revenuers confiscated her still and whiskey. With no source of extra income, she eventually sold the land for $10 and was never seen again.

Photo by Teresa Otto

Beating the Rap

Few women bootleggers spent time behind bars. Of those who were caught, most received a warning or fine. Jails weren’t equipped to have women inmates or their children. Butte widow Annie O’Day was caught with 250 gallons of mash. She fled to California with her four children. The Montana judge dropped all charges on one condition: Annie would forever stay in San Francisco.

Some women were flat-out too mean to go to jail. Mrs. Steve Gregovich greeted Sheriff Mahoney at the door with a pitchfork, said she’d use it on him, and was never approached again about the bootlegging business she ran from her kitchen. Though she did pay a fine for making 905 gallons of grappa—well over the 200 gallons allotted per year for a household. The incoming freight cars loaded with crates of grapes were hard for lawmen to ignore.

Josephine and Bertie’s brews were more discreet. They used local crops and fresh mountain water. Texas-based Saint Liberty Whiskey honors these two bootleggers with Bertie’s Bear Gulch Whiskey and Josephine’s Flathead River Whiskey—both of which are aged (unlike moonshine) and perfected in Montana with the pure water these bootleggers used.

The New Normal

In 1926, Montana voted to overturn the 18th Amendment—the first state to do so. It had been an epic failure—with lost tax revenue and a high cost to enforce the unenforceable. The “Noble Experiment” failed to do away with alcohol or improve society.

The silver lining? It created opportunities for women to open their own businesses, help support their families, socialize in nightclubs, and raise toasts in public.

I propose we raise a toast in honor of these pioneering women. While we’re at it, let’s raise a toast to the historians, authors, artists, whiskey makers, and of course, the Montana Historical Society who keep the memories of Montana’s women bootleggers alive. Cheers!

Black Woman's Still Painting Courtesy of Jane Stanfel

- Reply

Permalink