The Salish Discovery of the Corps of Discovery

In the published journals of Lewis and Clark, which run a little under 400 pages, less than one page is devoted to the "discovery" of the Corps of Discovery by the Salish at the south end of Montana's Bitterroot Valley. Likewise, Stephen Ambrose makes only passing reference to the event in his critically acclaimed account of the expedition, Undaunted Courage. As a result, this chance encounter does not feature very prominently in the usual narrative of the Lewis and Clark story. However, the paucity of that account from the two captains and others of the Corps who kept journals belies the absolute importance of that chance encounter to their success.

From the journals, we learn only the bare facts. It was September 4, 1805. They had had a very difficult time climbing out of the North Fork of the Salmon. The steep terrain and deep snow left many of the horses lame from falling. A lack of forage and game left both humans and horses hungry and weak. They needed food and fresh horses or they were not going to make it over the Bitterroots, later described by Lewis as "the most terrible mountains." Being already September, time was running out before snow would completely close their route.

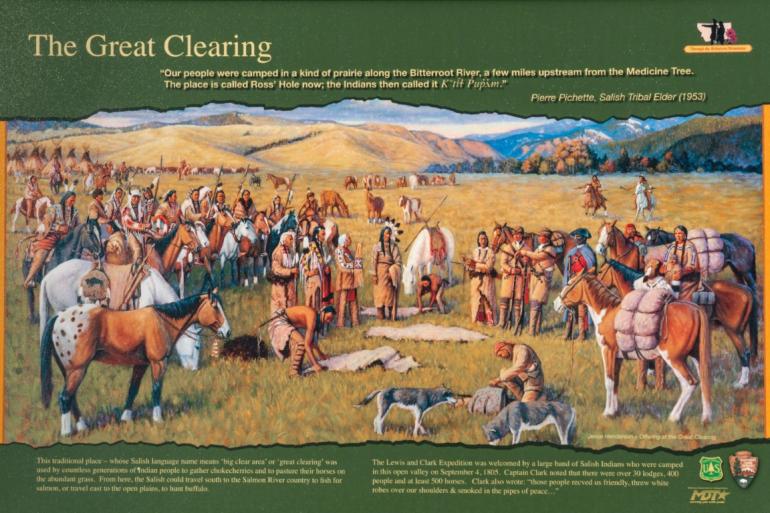

They came down a steep drainage and into a spot the Salish call the "the Big Open Area," or "the Great Clearing," now known as Ross' Hole, near present-day Sula, and befriended a band of Salish camped there.

Clark recorded that there were 33 lodges and 80 men, a total of 400 people, and about 500 horses. The Salish were friendly and, although their own food supply was low, were very generous as they shared the roots and berries they had, offered their guests buffalo robes and smoked into the night.

View of the Great Clearing today. (photo by Doug Stevens)

On September 5th, the expedition traded for what they needed to carry on. Clark records that "I purchased 11 horses & exchanged 7 for which we gave a few articles of merchandise. those people possess ellegant horses." This was a difficult, lengthy process, as no one in the Corps spoke Salish. Ordway notes, "these natives have the Stranges language of any we have ever yet seen." Clark adds that dialog was "with much difficulty as what we Said had to pass through Several languajes before it got to theirs[.]"

If that's all posterity had to go by, this part of the Lewis and Clark story might end there.

However, the Salish being a culture of oral history, stories of that encounter have been handed down through the intervening generations from Salish ancestors. Some stories were recorded at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Some were recorded more recently. The Salish Pend d'Orielle Culture Committee have gathered and published these stories in a book titled The Salish People and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Taken altogether, they paint a somewhat different story, adding color, context, and a few surprises to the 200-year-old tale.

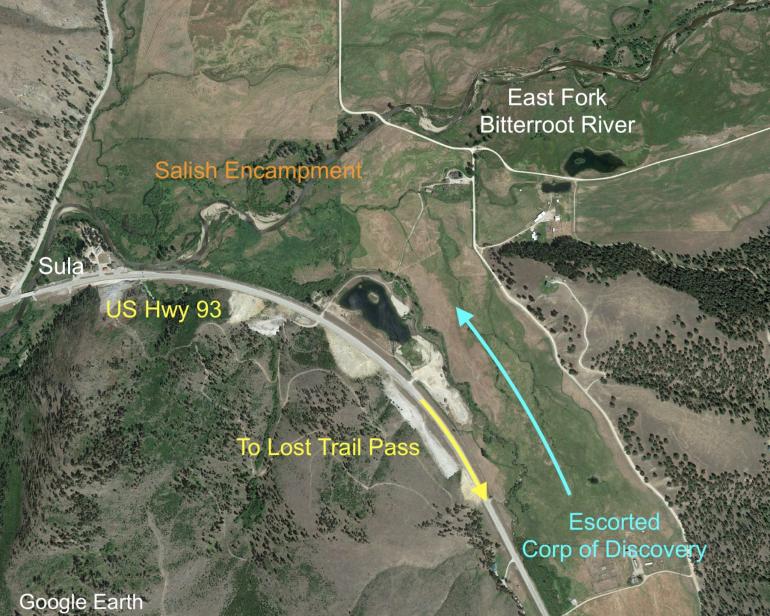

Many elders were interviewed for this collection and, while some of the details and focus of the stories vary a little, a general sense of what happened from the Salish perspective emerges. The Salish had been camped at the Great Clearing preparing for their annual trek to the east of the mountains for buffalo meat. On that day (Sept 4), Chief Three Eagles had been out with a "security detail," looking for any sign of a hostile tribe who might be trying to steal their horses. In a meadow along what is now known as Camp Creek (for obvious reasons), he saw the Corps emerge from the timber, having picked their way down the drainage from the ridgeline of Lost Trail Pass, which U.S. Highway 93 follows today.

Google Earth photo of The Great Clearing and Camp Creek.

The Corps presented a bizarre sight to the Chief, so utterly different from anything he had seen before. They were men of an ashen complexion (except for the black man) and short hair, and had no blankets. Interpreting based on his culture, the Chief thought that their numbers meant these were the last remnants of a tribe that had been attacked and nearly wiped out by another hostile tribe. Their paleness meant they were in feeble physical health, probably near starvation and cold, a suspicion seemingly confirmed by a lack of blankets, perhaps because this other tribe stole them all. Their short hair meant they were in mourning from losing the battle.

Then there was York, Clark's slave and a constant source of awe to the Native Americans he encountered. In Salish culture, when a man paints himself black, it is due to bravery proven in battle, so the sight of York reinforced his interpretation that these were survivors of a battle. The black one must have been their best, bravest warrior from the recent skirmish.

The party moved slowly through the valley, with the two "chiefs" in the lead, carefully surveying their surroundings. They had no apparent hostile intentions.

Additionally, with them was a woman with an infant. No tribe would send a woman with child into battle. Therefore, these people probably did not pose a danger to his people.

Chief Three Eagles returned to camp to alert everyone of the approaching strangers. He instructed a party to go out from the camp and bring them back safely. No one was to harm their strange new visitors.

They brought the Corps into the center of the Salish camp. One can imagine the commotion this would have made. The captains shook hands with the Chief and proceeded to unload their worn-out horses. When the Chief saw they had no blankets to sit on, he ordered some of their best buffalo robes for the captains. When the robes came, Lewis and Clark put them around their shoulders rather than sit on them.

East Fork of the Bitterroot River, near the 1805 Salish encampment (photo by Doug Stevens)

This was a real breach of protocol, so obviously, communication must have been poor, at best. The Chief offered them a smoke, but they found the Indian tobacco harsh and did not like it. In return they offered the Chief some of their eastern tobacco. To the Indians, this was very strong and caused them to cough, which was quite humorous to the onlookers. In the end, the captains asked for some kinnikinnick and mixed their tobacco with some of that, and the mixture was enjoyed by all.

They were fascinated by York, who drew a crowd. They rubbed his cheek and were surprised that his color did not rub off; stroking one's index finger across one's cheek became the sign language for a black person thereafter.

When it was time to retire, they returned the buffalo robes, again a breach of Salish protocol, as these were gifts, and unpacked their own blankets for sleeping; very strange behavior indeed.

The next day is when the captains got down to the business of trading for horses. As mentioned, communication was exceedingly difficult, as the Salish language was foreign to them. However, as luck would have it, a Shoshone youth lived amongst the tribe. He could translate the Salish into Shoshone for Sacagawea, who then passed the message on to her husband, Charbonneau, in Hidatsa. He then translated the message into French for Labiche, who was then able to translate it into English for the captains. Along the way, Drouilliard, fluent in Indian sign language, was probably used to augment the translation. The reverse process was used to translate the captains' English back down the chain to Salish. That's six languages for every exchange!

Interpretive Sign at Ross' Hole (Great Clearing), featuring painting, "Offering at the Great Clearing" by Native artist Jesse Henderson of the Corps of Discovery arriving at the Salish encampment, Sept 4, 1805. (photo by Doug Stevens)

This must have been both a comical and frustrating event to witness, and, of course, prone to misunderstandings, but eventually a deal was struck. The Salish would give the expedition the 11 horses, as well as a few colts for possible food along the way. The Salish would take seven of the Shoshone horses Lewis and Clark had gotten earlier from Sacagawea's brother, Cameahwait, plus a few "trinkets ."Often non-Indian commentators remark that this was shrewd bargaining, and if the Salish had known just how bad off the Corps were, they could have got a better "deal."

Oral history tells a different story. Yes, there was an exchange, but not a "deal." From the Salish perspective, like the returned buffalo robes, these were gifts. Not mentioned in the journals were also ten saddles, precious items, as saddles represented hours and hours of work through the summer by the Salish women.

As Ordway duly noted: "they are the likelyest and honestest we have seen and are verry friendly to us. They Swaped to us Some of their good horses and took our worn out horses, and appeared to wish to help us as much as lay in their power."

By September 6, they were back on their way. Chief Three Eagles had appointed a small contingent of Salish to accompany them to the edge of Salish land to ensure their safe passage. They reached Lolo Creek on the 9th and camped at a place Lewis called Traveller's Rest. They stayed there two nights before heading up the creek to Lolo Pass, passing by Lolo Hot Springs, and left Salish Country on the 13th.

They emerged from those "most terrible mountains" two weeks later having barely survived their ordeal.

There, they met the Nez Perce on the Weippe Prairie above the Clearwater River, gathering camas —another friendly tribe that would again save their lives and their mission.

These two events serve to underscore how the Corps' success and, indeed, their very lives depended on the goodwill and generosity of the friendly tribes they encountered along the way.

- Reply

Permalink