The Odyssey of Hugh Glass: A Bicentennial Tribute

On or around August 23, 1823, near the forks of the Grand River in northernmost South Dakota, Hugh Glass experienced the nightmare scenario for anyone traveling in grizzly country. In a thicket, he unexpectedly came into close-quarters contact with a sow, one accompanied by cubs. Combat erupted almost immediately.

James Hall, who published the first account (1825) of Hugh’s harrowing encounter, reported that his assailant was so close that, when Glass first became aware of its presence, Old Ephraim charged and caught him “before he could set his triggers.” Philip St. George Cooke (1830), on the other hand, asserts that Glass fired one well-targeted round that ultimately proved to be fatal; its immediate effect, however, served only to “raise to its utmost degree the ferocity of the animal.”

When his comrades in arms rolled the enormous bear off of Glass, they were astonished by the number and severity of his wounds. Edmund Flagg (1839) emphasizes that Glass received “not less than fifteen wounds, any one of which under ordinary circumstances would have been considered mortal.” Cooke’s graphic description indicates that the bear’s claws literally scraped flesh from the bones of the shoulder and thigh. George C. Yount’s narrative strongly suggests that another wound perforated the windpipe, which spurted a “red bubble every time Hugh breathed.” Biographer John Myers Myers enumerates lacerations to Hugh’s scalp, face, chest, back, and “one shoulder, arm, hand, and thigh,” based on specific details in various accounts.

Overnight, his condition teetered precariously between life and death. Glass, however, would not surrender to the Grim Reaper, so a makeshift litter was constructed to carry him. According to Flagg, Glass was transported thusly for two days “and a bit.” At a well-watered grove, Andrew Henry informed his men that this was a good place to stop risking the entire party for one man who almost certainly would not survive. He requested that two volunteers stay with Glass until he expired. As compensation for the danger involved and their subsequent service as a burial detail, Henry offered an “extravagant reward.”

Sources generally concur that John Fitzgerald volunteered for this task. Circumstantial evidence suggests that his partner was Jim Bridger, but supporting documentation is paper-thin. Yount and Cooke characterize this person simply as a youngster of seventeen. In commentary pertaining to this point, Myers Myers notes that Bridger was apparently the “only member of either of Ashley’s first two expeditions who wasn’t at least twenty-one.” Flagg identified this shadowy figure as “Bridges.” Hiram Martin Chittenden, the pioneering fur trade historian, later concluded that the trapper in question was, indeed, Bridger, based primarily on data from Joseph La Barge, a former steamboat captain. However, J. Cecil Alter, author of James Bridger, challenges Chittenden’s “authority to either confirm or contradict La Barge’s statement,” given the absence of direct references to Bridger in early accounts of this saga.

The vigil observed by these men lasted from four to six days. When their resolve broke, Fitzgerald was, by all indications, the first to crack. At that time, Hugh’s throat injury made speech impossible, but his hearing was unimpaired, and he later told Yount about arguments that Fitzgerald used in persuading his accomplice to abandon Glass. When they finally did so, they took virtually all of his possessions. Theft of Hugh’s rifle was a particularly egregious offense, one that breathed unquenchable fire and renewed purpose back into Glass.

Prior to their departure, Hugh’s attendants placed his litter next to the spring by which they were encamped. From that position, Glass could extend his arm and obtain water or buffalo berries, which dangled from overhanging bushes. To swallow them, however, Hugh had to crush berries to a pulp and further soften them with water.

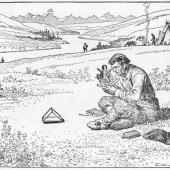

Several days later, manna assumed the form of a rattlesnake that Glass noticed after waking from a nap. The rattler’s immobility and bloated condition indicated that it was digesting a recently consumed animal or bird, which gave Hugh the opportunity to safely kill it with a sharp stone. Despite the difficulty of laboriously shredding and swallowing its raw flesh, the snake’s trunk provided the first substantive food that Glass had eaten in many days. The sustenance afforded by that reptile gave Hugh enough strength to crawl but not to walk. And, so, the arduous pursuit of his deserters began.

Without his rifle, Glass had to fully utilize every available food resource. Yount states that Hugh excavated “nourishing roots, [which] he had learned to discriminate.” This reference may signify consumption of prairie turnips (Psoralea esculenta). Glass also employed the Plains Indian practice of cracking open the long bones of bison carcasses and scraping out the calorie-rich marrow, to which he added buffalo berries.

Glass eventually struck the proverbial mother lode when he saw several wolves kill a young buffalo calf nearby. According to Cooke, Hugh waited until they devoured about half of the carcass, after which he appropriated the remainder. For someone who had lost as much blood as Old Glass, the greatest need was food capable of replenishing it. “Dripping with gore, the chunks he ripped from the young buffalo” were, as Myers Myers observed, “just behind a blood transfusion in the immediacy with which they joined forces with his system. With his arteries flush for the first time since his terrible encounter, he was now on the way to rising from all fours.”

Indeed, Hugh systematically exploited this windfall. Resting beside the buffalo carcass and periodically dining off it, he allowed his body to recuperate as thoroughly as possible. When he resumed his journey a few days later, Glass had regained bipedal locomotion.

His increased blood volume and improved circulation accelerated the healing process, but Hugh’s back wound, which he could not reach, became infested with maggots. As he proceeded downriver toward Fort Kiowa, he encountered Sioux Indians, who thoroughly cleaned and treated his wound with an “astringent vegetable liquid.” Sources suggest that the Sioux also provided access to a horse or buffalo-hide bullboat.

His increased blood volume and improved circulation accelerated the healing process, but Hugh’s back wound, which he could not reach, became infested with maggots. As he proceeded downriver toward Fort Kiowa, he encountered Sioux Indians, who thoroughly cleaned and treated his wound with an “astringent vegetable liquid.” Sources suggest that the Sioux also provided access to a horse or buffalo-hide bullboat.

In either event, Hugh arrived at Fort Kiowa no later than October 11. Following acquisition of supplies and weaponry, Glass headed back upriver, probably by pirogue or a Mackinaw boat, toward the Mandan villages. His party reached their objective by November 20, but Glass narrowly escaped an Arikara attack. Four separate accounts corroborate his rescue by one or two mounted Mandans who took him to either their village or Fort Tilton.

Working initially from the premise that his quarry was then stationed at the mouth of the Yellowstone, Glass embarked, alone and on foot. This leg of his journey ultimately took him 550 miles to the newly established Fort Henry, located at the confluence of the Little Bighorn and Bighorn rivers. Travel conditions were miserable. According to Flagg, “snow lay on the frozen soil for the most part of his route a foot in depth!”

Nevertheless, Yount relates that Hugh appeared unexpectedly at Fort Henry on New Year’s Eve. Glass confronted Jim Bridger, whom Myers Myers regarded as one of the deserters. Unprepared for the sheer terror exhibited by the 19-year-old youth and recalling conversations he overheard on his deathbed, Glass forgave Bridger. Reverend Orange Clark, who transcribed Yount’s narrative, indicates, however, that Glass departed Bridger with food for thought: “I leave you to the punishment of your own conscience and your God. [Hereafter, don’t forget] that truth and fidelity are too valuable to be trifled with.”

As winter worsened, Glass had to postpone his pursuit of vengeance until February 29, 1824, when he volunteered for courier service on a contingent headed to Fort Atkinson. Unfortunately, another skirmish with Arikara Indians, which took place near the historic site of Fort Laramie, left Glass, once again, unarmed, alone and on foot. After traveling some 400 miles to Fort Kiowa, he learned that John Fitzgerald had given up beaver hunting and enlisted in the Army.

Given Hugh’s unwavering commitment to his mission, it is entirely possible that Glass would have executed Fitzgerald when their paths crossed at Fort Atkinson in May or June of 1824, had it not been for the Army’s intervening authority. Even so, that encounter was volatile. As Myers Myers observes, the officer of the day, Captain Bennet Riley, informed Glass that he “couldn’t have one of the post’s soldiers to eat.” To his credit, Riley ensured that Hugh’s rifle was promptly returned to him. That act, in conjunction with a “purse of Three Hundred Dollars,” which Yount insists that members of the Sixth Regiment donated to Glass, finally extinguished the fires of vengeance that had fueled Hugh’s behavior.

Literary and cinematic portrayals of this saga have consistently and understandably emphasized the life-and-death struggle for survival that occurred during the weeks immediately after his near-fatal grizzly attack. Fully contextualized, however, Hugh’s journey constitutes nothing less than an American odyssey, one that pitted Glass against extraordinary odds, the destructive power of an enraged grizzly, brutal weather and Arikara war parties, for more than nine months and 2,000 miles, much of which he traversed alone and on foot. These events justifiably gave rise to one of the West’s most enduring legends.

Leave a Comment Here

My family has lived here in the mountains since the 1840s and I am always amazed at how many different ways the history has evolved over generations of people who have come to explore the history of Rocky Mountains.

- Reply

Permalink