Claws, Teeth, Armor and Cheats

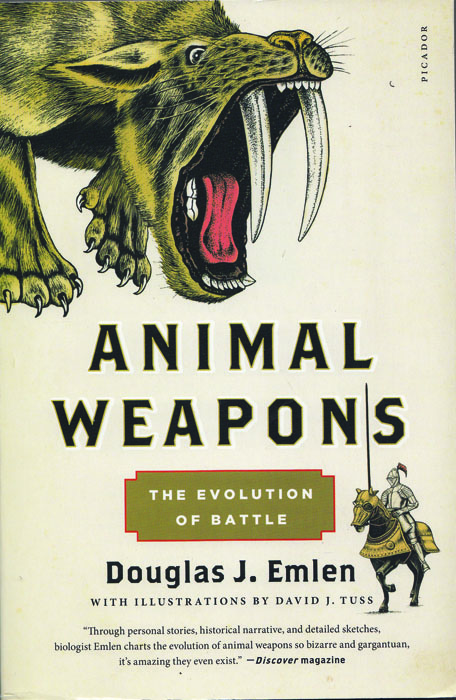

Excerpt is from Animal Weapons ©2014 by Douglas J. Emlen, published by Picador

For as long as I can remember I’ve been obsessed with big weapons.

One cold, mountain night in early fall — peak of the rut for elk the author and a buddy were camped in a tent. “Almost a ton of testosterone-driven rage exploded beside us not twenty feet away.” Two bulls were locked in combat. “Hindquarters whirled by our tent as they quickstepped their ancient dance, oblivious to the world around them. Images from that night stay etched in my mind.”

As I grew and, in particular learned more about biology, I realized that “big” had little to do with absolute size. Extreme weapons were about proportions. Some of the most magnificent structures are borne by tiny creatures.

CAMOUFLAGE AND ARMOR

Leaf-mimic katydids even rock back and both when they walk, resembling a leaf fluttering in the wind.

Many animals use chemical weapons against their predators, either synthesizing toxins, or extracting (and sometimes modifying) toxins from their food. Some caterpillars ooze droplets of poison from glands near the bases of tiny barbed, needlelike hairs.

TEETH AND CLAWS

Carnivore teeth are small because individuals with unusually large teeth performed poorly when hunting their particular prey.

Teeth, claws, and claspers are sharp and lethal, but not particularly large or spectacular. Such are the canines of lynx: longer than the surrounding teeth and effective for separating the spinal vertebrae of hares, but not so large as to hinder overall agility or head angle in any way, and definitely not large enough to impede the speed and coordination so essential to lynx survival.

Teeth face trade-offs in shape as well as size. One tooth cannot excel at all tasks. Long and slender canines are very effective at piercing skin, muscle, or viscera, but these same teeth can snap if they strike bone. Sturdy, bladed teeth, especially if they line up precisely with other sharp and bladed teeth on the opposite jaw, are great for shearing through muscle and sinew. But the blades fracture if they are used to crush or grind bone. Alternatively, wide, solid, dome-shaped teeth are great for cracking bone to reach the nutritious marrow, but they are useless at slicing, piercing, or puncturing.

A survey of both living and extinct carnivores shows an astonishing frequency of natural tooth breakage, with one out of every four teeth chipped, cracked, or shattered.

COMPETITION

Why should just one sex have weapons? And why is it (almost) always the males? We have to go back to the beginning for the answer: eggs and sperm. Both sexes offer a copy of their genome to every child, but the packages they come in are different. When sperm and egg launch a new life, it’s the resources provided by the mother that first feed it. Development is expensive, and eggs provide the energy and nutrients sustaining this process. Females of all species produce larger reproductive cells than males. Eggs are bigger than sperm, and this difference is far more substantial than most of us appreciate. With the same amount of resources, males produce millions of sperm. The simple fact is that in virtually every animal species there are nowhere near enough eggs to go around. The result is competition.

Another reason is that large nutrient-rich eggs are expensive, and they take time to produce. Depending on the species, females may take days or even weeks to recover from producing one batch of eggs before they are ready to lay another. Males, on the other hand, tend to need only a few minutes. Preparing nests, pregnancy, guarding eggs, and feeding and protecting young all take time. Enter natures’s most pervasive and potent form of competition, what Darwin coined “sexual selection.” Individuals of one sex compete for access to the other.

SNEAKS AND CHEATS

When only a few dominant males monopolize access to reproduction, there’s a strong incentive for the rest of the males to break the rules. You can’t win the game the normal way, cheat. Sneaky males are everywhere. Bighorn sheep rams guard harems on sheer slopes high in the Rocky Mountains. The largest and oldest males have by far the biggest horns, and these males consistently win ownership of the harems. Yet, as many as 40% of the lambs end up sired by smaller males.

Male sunfish and salmon guard cleared patches of sand where females come to lay eggs. Females chose large, attractive males with the best territories, sidling up next to them so they can shower sperm over her eggs. Tiny males have no chance of defending a territory or being picked by a female, so they dart in surreptitiously and squirt clouds of sperm in the mix.

Coursers, squirters, satellites and female mimics — there are many ways to cheat. For animals, this means that in addition to traditional confrontations with armed rivals, dominant males now face the more insidious threats of male breaking the rules. Similarly, guerrilla forces, land mines, IEDs, and cyberhackers all can undermine the effectiveness of conventional military forces.

CASTLES

We manufacture our weapons using materials taken from the environment, and these structures exist as separate entities from ourselves — we can throw them away or modify them, if we want to, whereas animals are stuck with the weapons their bodies grow.

But animals manufacture structures, too. Termite fortresses, beaver dams, bird nests, spiderwebs, and mouse burrows are all manufactured structures. They’re not part of the bodies of the animals that make them.

Today’s [human] world is a quagmire of rivalries and factions, ethnic disputes, and religious wars, and the last thing we need is for large and

unknowable numbers of these players to be armed with weapons of mass destruction.

EXTRA NOTES FROM THE BOOK

- Elk pay a steep price for their weapons. Bulls double their daily energetic needs and leach essential minerals away from other bones in order to grow antlers.

- Cats are agile predators whose weapons are moderate in size, reflecting a balance between selection for killing large prey and selection for agility and speed.

- Ambush predators snatch prey with a quick strike from claspers. (Mantisfly).

- Dung beetles use horns to tunnel for burrows containing females.

- When males fight in unrestricted places, such as in the air, or in chaotic scrambles, agility takes precedence over big weapons. (Cicada killer wasps).

- Duels are an essential ingredient of an arms race. When rival males face off one-on-one, selection often favors the male with the bigger weapons, driving evolution of extreme weapons sizes. (Deer, Moose)

- Fallow deer and moose pay exorbitantly for their weapons, and for the stamina and energy needed to win fights during the rut, suffering gashes, infections, and depleted energy reserves. Three-quarters of deer bucks die without ever succeeding in defending territories, and 90% fail to mate even once in their lifetime.

Leave a Comment Here