Wild West Words: Eureka!, Gold, Muskrat

The Curious Origins of the Western American Vocabulary

Eureka!

A suspicious king. His golden crown. A naked mathematician screaming through the streets of an ancient city. What we have here are the ingredients for the birth of a word.

To put flesh on the bones of this story, we time-travel to the island of Sicily in the third century B.C. The Greek city-state of Syracuse was ruled by the tyrant king Hiero II, who commissioned a craftsman to create for him a crown of pure gold.

Suspecting that the goldsmith may have adulterated the artifact with cheaper metals, Hiero consulted his countryman, the inventor and mathematician Archimedes to assess the quantity of gold in the crown.

After contemplating his task for weeks, Archimedes arrived at the solution as he stepped into a public bath and watched the water level rise around his submerging body. In a flash, he had discovered the principle of displacement needed to measure the density of gold in the king’s crown.

The elated Archimedes launched himself out of the water crying “I’ve found it! Eureka! Eureka!” he yelled in his native Greek as he streaked down the streets of Syracuse.

Though most historians believe Archimedes did indeed discover the principle of displacement, the story of his public nudity is probably a popular embellishment. And the word? Whether he uttered it or not, eureka has thundered down through the ages as a happy cry of discovery.

Gold

Attached to the story of Archimedes, the golden crown, and a sudden discovery, eureka got a lot of airtime in the gold fields of the American West. The word appeared on the California state seal created in 1849, one year after gold was discovered at Sutters Mill in central California. In the popular mind, the hills resounded with happy eurekas as forty-niners retrieved gleaming gold nuggets from the American River. Perhaps the word reverberated around the gold-laden Montana gulches near Bannack, Virginia City and Helena during the strike-it-rich decades of the 1860s and ‘70s.

Gold is surrounded by a lush vocabulary. The word itself has a long romance with our language, appearing in Old English texts in the 1200s. The verb gild “to cover with a thin layer of gold” is etymologically related; it showed up in documents dating from the 1300s. If you speak German, you know that Geld means “money.” A Dutch coin is a guilder. These Germanic-language terms are etymologically related to our gold.

On the Romance branch of the language tree we find oro (Spanish) and or (French). These hail from their Latin source aurum, which also gives English the adjectives aureate and auric, “golden.” And that Latin word, incidentally, is the source of Au as the abbreviation for gold on the periodic table of elements. If you’ve ever wondered why the symbol for gold on the periodic chart is Au, and not something more familiar like Go or Gl, blame Latin!

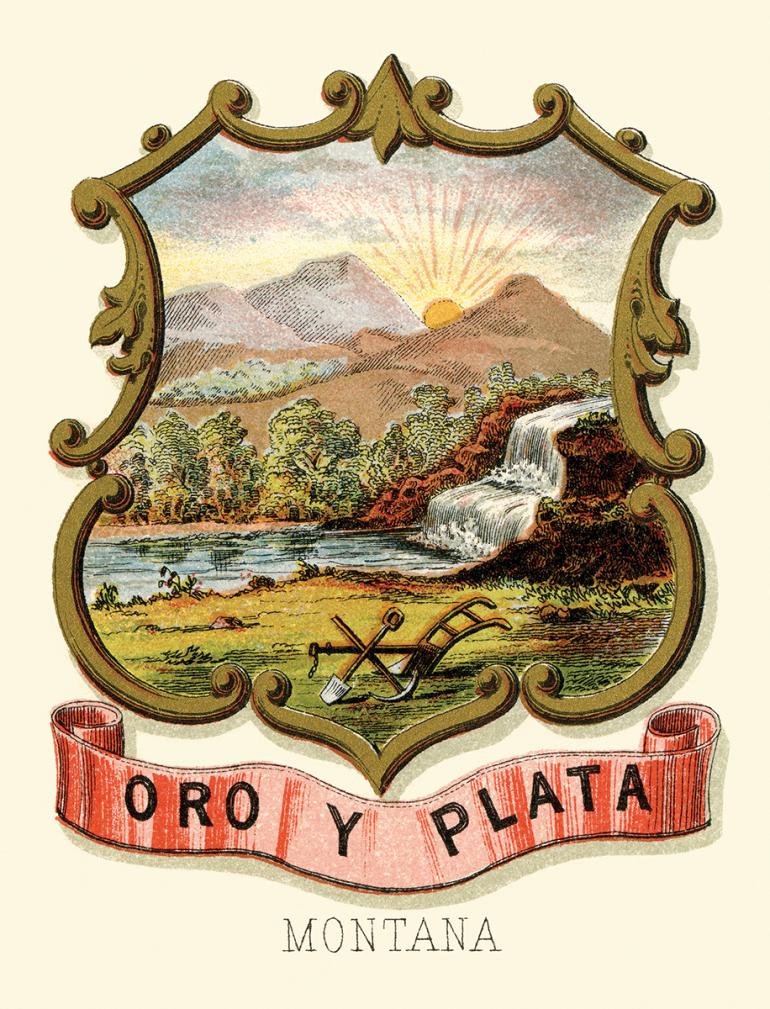

Montana’s official motto Oro y Plata is the Spanish “Gold and Silver,” reflecting the riches to be found in the Treasure State.

Muskrat

Short, thick brown fur. Six pounds soaking wet. Spends most of its time in and near the water. Eats cattails and water lilies. A bit dank and fetid. Long, scaly, hairless tail.

That’s the c.v. of the muskrat, semi-aquatic rodent and denizen of the entirety of the North American continent. The critter’s common name seems to have been inspired by its dank fetidness and its scaly rat-like tail. Easy enough.

But not so fast.

Historical dictionaries reveal a more complex story behind the name of this ubiquitous American rodent. As it turns out, the Algonquin-speaking natives of the American east coast called the critter moskwas (literally “it is red,” so called for its coloration). The word, pronounced something like “musquash” was adopted by early English colonists. That the first Algonquin syllable matched the English “musk” was a happy coincidence for the European newcomers.

In 1778, American explorer and journalist Jonathan Carver offers his observation of the rodent and the origin of its name in his publication Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America: “The Musquash or Musk-rat,” he writes, “is so termed for the exquisite musk it affords.”

Other early writings suggest the muskrat was valued for both its fur and its “exquisite musk.” From 1620: “Muske Rats skins, two shillings a dozen: the cods of them will serve for good perfumes.” American surveyor John Lawson, in his 1714 History of Carolina notes “Musk Rats frequent fresh Streams and no other; as the Bever does. He has a Cod of Musk, which is valuable, as is likewise his Fur.”

Leave a Comment Here