Excerpts from John N. Maclean's latest book "Home Waters: A Chronicle of Family and a River"

Home Waters: A Chronicle of Family and a River, published by HarperCollins and available wherever books are sold, is the latest book by John N. Maclean, noted author and the son of Norman Maclean. It features engravings by Wesley Bates. Read our review of Home Waters here.

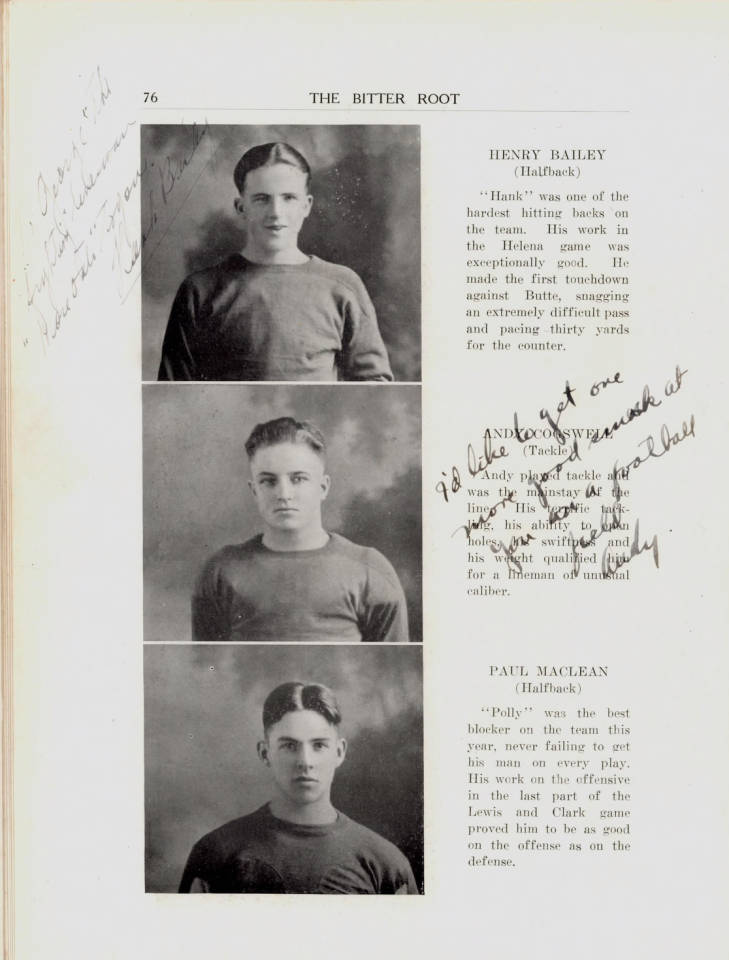

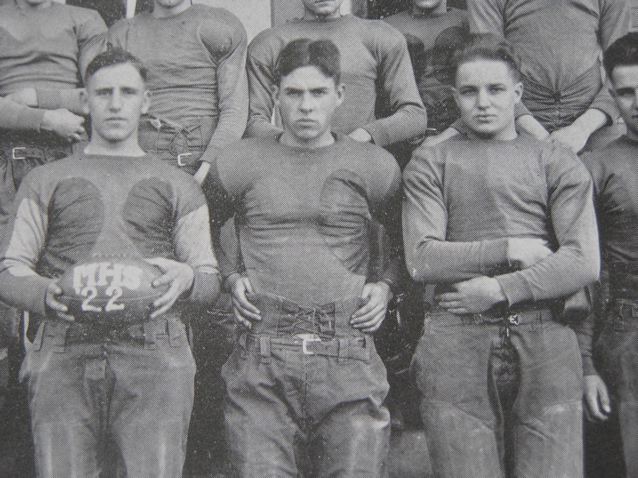

On the last full day of Paul Maclean's life, Sunday, May 1, 1938, he had about $50 in his wallet, having cashed a two-week paycheck. He took his girlfriend, Lois Nash, twenty-nine, a redheaded Irish nurse, to an afternoon White Sox game at Comiskey Park at Thirty-Fifth and Shields. She later said she and Paul had been dating for two months and were engaged to be married, which came as news to his brother and sister-in-law. The White Sox played the St. Louis Browns, who won by a score of 7 to 5.

Paul made a day of it and took Lois for a leisurely dinner at Hyde Park's best restaurant, Morton's at Fifty-Fifth Street and Lake Park Avenue. After dinner they visited friends, and Paul then delivered Lois back to her place at 5143 Kenwood Avenue. He left about ten-fifteen p.m., saying he was headed home. Paul walked south across the midway toward his lodgings at the Weldon Arms Hotel, 6235 Ingleside Avenue, just a couple of blocks from where Norman and Jessie lived, at 6020 Drexel Avenue. But he did not go home.

The following events occurred within a few blocks of each other just south of the university, in the Woodlawn neighborhood near where Paul lived. Not long after midnight, on Monday, May 2, Sidney Sorenson saw a man behaving strangely across the street from his home in the 6200 block of Eberhart Avenue. The man threw himself to the ground and then arose, pretending to stagger and walked a short distance away to the corner of Sixty-Third Street and Eberhart Avenue. Sorenson said "two colored women and a Negro man" apparently became alarmed and moved off as the man approached. He saw the man, whom he later identified as Paul, at one-fifteen a.m. --- it's not clear how an identification was made. Another witness, A.D. Adkinson, who lived nearby on East Sixty-Fifth Place, said he saw a young man scuffling with two others at Sixty-Third Street and Drexel Avenue that night. The man, whom Adkinson identified as Paul, walked away from the scuffle and the others drove off in a car. Then shortly before five a.m., Edward Miller was awakened by loud talking in the alley behind his home at 6234 Rhodes Avenue. He got up and looked out into the yard but saw no one and went back to bed. When the noise persisted, he got dressed, went out to investigate, and found a man lying unconscious in the alley. Miller didn't have a phone in his home and had some trouble finding one to call the police. When he did, the address he gave was garbled. It was not until six-eighteen a.m. that the Chicago Police received another call of a man down in the alley behind Sixty-Second Street and Eberhart Avenue. They found Paul alive but unconscious where two alleyways join in a T. Police found his wallet nearby, empty, and three $1 bills and a dollar in change in his pockets. Police also found in one of his pockets a matchbook for the Vogue liquor House, a bar near where he lived. He was transported to Woodlawn Hospital, where nursing staff at first thought he was passed out drunk. When they turned him over, however, they discovered a deep wound in the back of his head indicating that he had been severely beaten or struck with a heavy object. He did in the hospital at one-twenty p.m. without regaining consciousness.

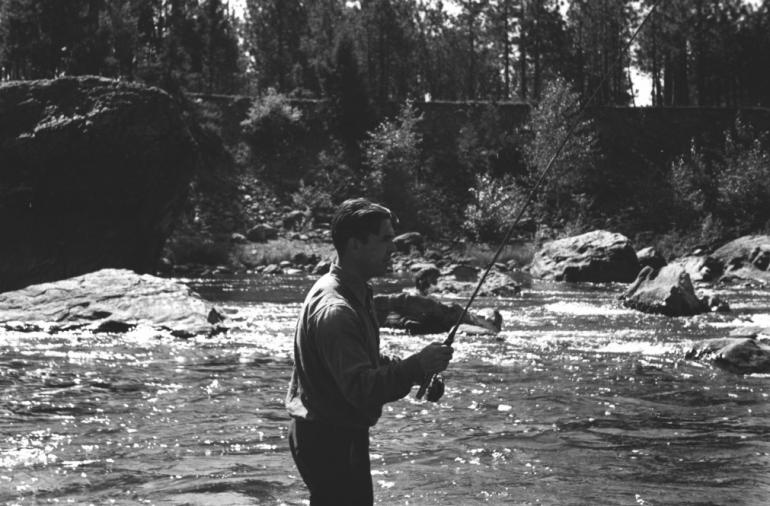

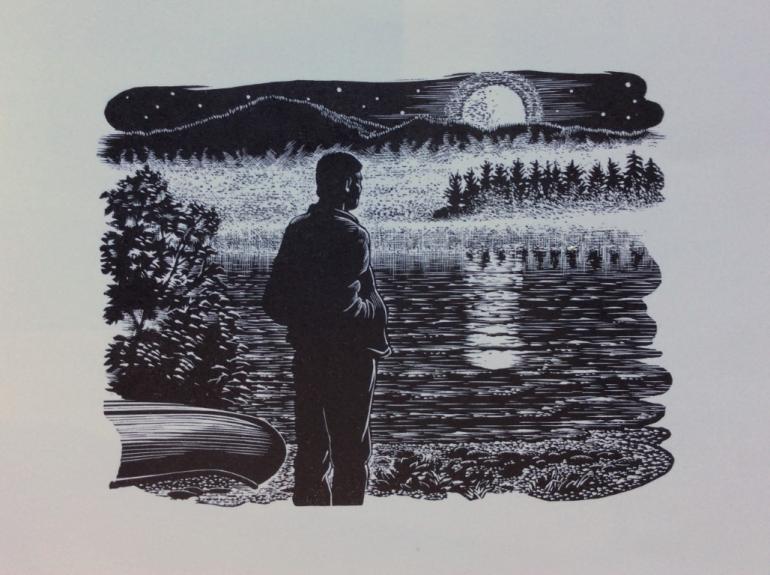

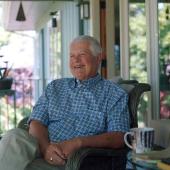

Photo by Norman Maclean, Provided by John N. Maclean

Those are the bare facts from police and coroner reports and from the account in the Chicago Tribune, which my father said covered the story accurately and with restraint. The murder was a sensation, though; the alley where Paul was found was near Sixty-Third Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, known as "sin corner." It was said that every vice known to man was for sale there, and not every newspaper handled the story with the same care as the Tribune did. The New York Post, for example, reported that prostitutes had been active in the vicinity that night, but the police investigation found no link between them and Paul, and such activity in that neighborhood was hardly a rarity.

My father speculated that Paul had gone wandering through the neighborhood that night, as he had done as a reporter back in Montana, simply to acquaint himself with his surroundings. "He liked to walk around in odd sections of the city," Norman told a coroner's inquest. "He was a newspaper reporter by trade, and he was from a small town. He liked to walk around, just to see the town, Saturday afternoons and sometimes at night. I had warned him that this was not Montana, and he couldn't walk around with impunity looking at the sights, but he didn't seem very particularly persuaded by my argument." Jessie [Norman's wife] thought it possible Paul had gone looking for trouble, as he sometimes had in Montana, and then found that Chicago didn't play by Montana rules. She often wondered if he had been given just a few more years and a lot more luck, whether he might not have turned a corner, married, started a family of his own, held a steady job, and found supportive friends. Paul would've had to give up a lot, though, for that sort of life.

An investigating officer, Detective Sgt. Ignatius Sheehan, became interested in the story of the feigned stagger, and knowing that the university sometimes sent in private reports on vice in the district, he surmised that Paul may have been conducting an investigation for the school. University authorities denied this, as did my father and Paul's boss, George Morgenstern, who dismissed the theory as utter nonsense. Another theory was that Paul's gambling caught up with him and he was attacked for bad debts. But this scenario, which was carried through in the movie version of the tale, is quite unlikely for late on a Sunday night, in a heavily African American neighborhood, supposing that debt enforcers were sent to collect or encourage repayment. After several weeks of investigation, Deputy Coroner C.J. McGarigle asked the police officer who oversaw the inquiry, Capt. Mark Boyle, for his conclusion.

"Did the police come to an opinion as to how this occurrence happened, whether it was robbery or otherwise?" McGarigle said.

"I am of the opinion it was a robbery," Boyle replied. And that's the way it remains on the police books to this day: a robbery gone bad, a murder unsolved.

Photo by Norman Maclean, provided by John N. Maclean

Norman alone accompanied his brother's body back on the long, overnight train journey to Montana. When he once tried to tell me what the trip had been like, he couldn't find words. After the funeral in Missoula, he spent several seeks of compassionate leave with his parents at the cabin at Seeley Lake, and he was able to describe this experience years later.

"It was early May, and the forest floor of the cathedral of thousand-year-old Tamaracks was covered with dogtooth violets, which are really lilies. Around the lake they are often called glacier lilies, probably because it is only about twenty miles from our lake to the glaciers. We thought they were the most beautiful and fragile flowers we could ever see, and we tried not to walk on any of them. My father aged rapidly. He never hunted ducks again and had to give up most of his trout fishing. His feet dragged when he walked, as if his leg muscles had atrophied so he could not fish the big river anymore and even the creeks that were hard to get to. Mostly he fished in the lake in front of our cabin in a flat-bottomed boat he had made many years before."

If Paul's story had ended there it would have remained a shocking family tragedy best left in the past. It did not. The portrait Norman managed to create in A River Runs Through It gave Paul a lasting afterlife as the charming rebel, doomed but beautiful and gifted with a fly rod. He was forever the younger brother who struggled for an independent life and went down fighting. Norman's vision of him, though, brought the consolation of shared experience, taken to an eloquent level, to a host of brothers and sisters who have reached out to wayward siblings only to see them twist and dodge away as Paul did.

Many years later my father would come down from the cabin to the lake in the evening when the world had turned to gentleness, and I would sit on the bank watching for a fish to rise. Without acknowledging my presence but knowing I was there he would call out "Paul! Paul!" his face nearly incandescent with the light of remembrance and expectation.

Engraving by Wesley Bates, courtesy of HarperCollins

From Chapter Eight, “Fathers and Sons”

My younger son, John Fitzroy, whom we call JohnFitz, and I came west together and joined my father at the cabin several times during the years he was at work on the Mann Gulch story [Young Men and Fire]. My dad was in his early eighties, but he still drove alone to Montana from Chicago. After a stint at the City News Bureau, JohnFitz had been a reporter at the Montgomery Advertiser in Montgomery, Alabama, covering among other things a cross burning by the Klu Klux Klan in the southeastern corner of the state. But he was headed for law school. He went on to become a public defender for the state of Maryland, working in the division defending juveniles, and established his own family, his wife, Amy; daughter; Ashlyn; and son, Evan Fitzroy.

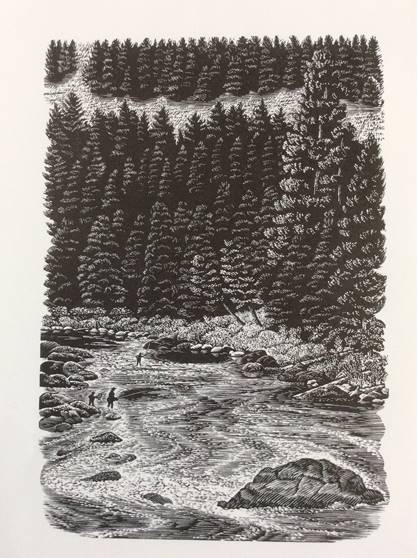

The first time JohnFitz, my dad, and I were at the cabin together, we decided to take a hike to Morrell Lake at the headwaters of Morrell Creek. The lake is a wonder spot. You can look from there to the tops of the rugged Swan Range that form the western edge of the Bob Marshall Wilderness. That’s where Morrell Creek gets its start, up around seven thousand feet where snow and ice can last into August. The creek comes down the mountains in a dramatic series of waterfalls, and the last one right before Morrell Lake is big and picturesque.

Back in the old days, when my dad was young, he’d had to hike more than twenty miles to reach Morrell Lake. But as logging roads extended into the backcountry, the trailhead moved closer to the lake and the hike shortened. By the time the three of us walked into the lake, the trail was down to about two and a half miles. On that trip we found a makeshift raft pulled up on the lakeshore, left by a previous outfit. Those remote mountain lakes are often ringed by timber and difficult to fish from shore, and fishermen who build rafts out of driftwood or fallen logs often leave them for the next group.

JohnFitz was too young to have taken up fly fishing, but he happily got on the raft and draped the harness of my wicker fishing basket over his shoulders. I waded out pulling the raft, using it as a float when we reached deep water, and hung on to the raft with one hand while casting with the other. When I caught a fish, I flopped it onto the raft, and JohnFitz unhooked it and put it in my basket. He was content as keeper of the fish. My dad sat on a log on the shore and he was happy, too, watching me fish in this odd manner with his grandson. I caught a gorgeous mess of cutthroat trout, the ones with the lush Morrell Creek coloring.

Photo by John Kelly, Promo Image for Robert Redford's Film Adaptation of A River Runs Through It

The next time we went to Morrell Lake we were all older by several years, and I should have been wiser. Once again, the three of us were at the cabin and looking for something fun to do together. I didn’t give it a second thought and said, “Why don’t we all hike into Morrell Lake like we did last time and do a little fishing?”

You have to get to the lake early for the morning rise, because the fish stop biting by about one o’clock. The water’s so cold your lower parts go numb if there’s no raft and you need to wade, which was the case this time. You need to arrive early, fish, and get out of the water promptly. We’d timed it just right, and when we arrived at the lake a general rise was underway. All across the lake, expanding circles of wavelets appeared on the barely rippled water as trout did a “head poke” or just sipped to take flies from the surface. It was a compelling sight as a new rise form, as they’re called, instantly came to life for every one that flattened and died out. I waded out and caught all I wanted in a short time: it was only a few, because by then I was working my way into the catch-and-release ethic.

JohnFitz stayed on the bank to keep my dad company. My father sat on a log looking happy but tired. I waded back to shore and offered my father the rod. “Dad, do you want to fish for a while?” I said. “It’s still early, the fish are still moving.”

He had this wonderful smile on his face, one that came from deep within and lit up the world. “I don’t need to do any fishing,” he said. “Let’s just hike out.”

We took it easy on the return trip and all went well until about the halfway point. My father by then was leaning backwards, tipping back at an alarming angle. He tried to smile, but his face was a grimace and he was having trouble making headway. We had about a mile to go.

“Go right along with him and talk to him, see what you can do,” I told my son.

JohnFitz already was helping him, without seeming to do it. He put a supporting hand on his grandfather’s back, not pushing but just encouraging him along, talking to him, letting him stop whenever he needed to rest. It got rough toward the end, but JohnFitz was tender and patient with him, and we made it back to the mainland without serious mishap.

“He’s a tough old bird, he did well,” JohnFitz said to me.

My father sat down heavily in the car’s passenger seat. “I’d like to go back to the cabin and have a rest,” he said. So that’s what we did. We’d left the gate closed on the short dirt road to the cabin, and when we turned onto the dirt JohnFitz offered to jump out and open the gate. Norman wasn’t having it. “I’ll do it,” he said, and stepped out and opened the gate. Once inside the cabin, though, he had a lie-down.

And that was the last fishing trip. The very last one.

Photo by John N. Maclean

Leave a Comment Here