Jim Harrison's Earthy Prose

“Have you had your oatmeal? I’ve just finished mine,” was the surprising opening sentence of an early morning telephone call from Jim Harrison, one of the world’s most famous gourmets, not to mention poet, novelist, essayist, screen writer and sportsman. If his writing on the fine art of eating is to be believed, and I firmly opine that it is, I would have imagined Harrison to whet his breakfast appetite on sweetbreads, wild leeks and cream. He had telephoned in response to my request for an interview.

On a clear early summer afternoon, I drove through the Paradise Valley to the ranch where, from late spring to early fall for the past four years, Jim and Linda Harrison have made their home. As I pulled into the driveway, Linda emerged from her fenced kitchen and flower garden, followed by Mary, the curly black English cocker spaniel who bounded towards me, barking and amicably wagging her tail in welcome. The author greeted me from the doorway with an invitation to look inside briefly before we repaired to his studio to talk.

An accomplished and prolific writer, at sixty-nine Jim Harrison’s literary output has earned him a place in the forefront of American Letters. As Elspeth Huxley would have put it, “He is a writer to his fingertips.” First and foremost a poet, we were celebrating the recent publication of his tenth book of poetry, Saving Daylight (Copper Canyon Press, May 2006).

A distinctive feature of Harrison hardcover books, and there are twenty-eight at last count — novels, novellas, and non-fiction alongside the poetry — is the jacket art depicting the finely muted western landscapes of Harrison’s friend and Montana resident, Russell Chatham. As I cast my eye around the walls of the restored ranch house, a comfortable and tasteful home, I was drawn to several Chatham originals.

“I met Russ in 1968,” Harrison told me. “We started fishing together. Richard Brautigan (Fly Fishing in America) occasionally joined us. Russell’s grandfather, Gottardo Piazzoni, was a well- known painter in San Francisco at the turn of the twentieth century.” The young Russell was inspired and molded by his grandfather’s influence. As a youth, Harrison said, he also had a hankering to be a painter. He studied art for two years and majored in Art History.

Russell Chatham is something of a Renaissance man. He excels at everything he does. Like Harrison he is a gourmet. His Livingston Bar and Grill was arguably the best eatery in Montana for several years until its recent closing. His publishing house, Clark City Press, has produced some of the most beautifully designed and unusual books of local interest, many of them now collector’s items. He first published and illustrated at least two volumes of Harrison’s work. It was Harrison’s daughter Jamie, a writer, who helped Chatham start up his publishing business.

Today Harrison and Chatham’s friendship is as staunch as ever after twenty-eight years. Harrison recounted a recent trip he and Linda, Russell and Liz took to visit San Simeon, the Hearst estate in California, which boasts thirty miles of magnificent Pacific seashore under conservation easement. Ferried there in a private jet, the friends enjoyed a weekend of feasting and conversation while absorbing the breathtaking natural beauty of their surroundings.

As we walked towards his studio, a rustic cabin adjacent to the main building, Harrison pointed out features of the landscape that gladden his heart and sharpen his literary senses before he disappears into the Zen-like monastic simplicity of his workspace. The nearby pond or wetland attracts varied waterfowl; most recently he had observed a pair of blue herons there.

Harrison told me that the property has an unusual history. It was once owned by the family of Evelyn Nesbit, a popular actress and artist’s model, who was at the center of an immense scandal. Her jealous millionaire husband Harry K. Thaw shot and killed the famous architect Stanford White on the night of June 25th, 2006, while he was attending a performance at Madison Square Garden. It was the creator of San Simeon, William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers that sensationalized the murder and subsequent trial, which was dubbed the “Trial of the Century.”

I followed Harrison into his studio. It was quite unlike any writer’s den I had been in. But then I remembered that Harrison is a practitioner of Zen, and the stark bareness of the room made sense. There is no clutter to distract the concentration; a chair and desk, pens and paper. In a far corner there’s a cot to rest on and a distant wall lined with shelves holding photos and memorabilia.

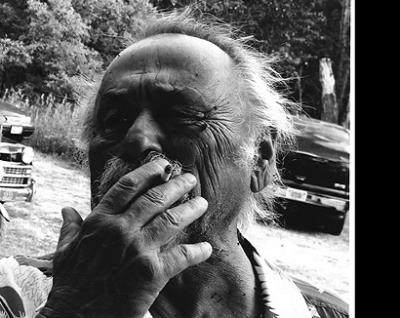

There is something untamed about Jim Harrison’s appearance: a solid frame loosely clothed, windswept hair, full-moon face, a slightly droll moustache, a wandering eye. He speaks with a drawl, reminiscent of his friend Jack Nicholson, but the words are precise, the mind razor sharp and witty, a quiet sneaky wit. He offers me a chair strategically placed so that we face each other without distraction.

One of five children, Jim Harrison was born in 1937 in Grayling, Michigan, where his father was a county agricultural agent. Harrison worked on the family farm from the age of ten and, he told me, he was pretty good at it. His forebears were Swedes. “I never forget anything,” he said, which must be a Swedish attribute. “We Swedes are as spontaneous as barbed wire.” His sister died when she was nineteen. Her death made a lasting impression on him. An echo of this tragedy has appeared in his fiction and poetry. His older brother John, who died in 2003, was Dean at the University of Arkansas and his younger brother is Dean at the University of Washington. Harrison realized at an early age that an academic career was not for him.

After graduating from Michigan State University, where he met fellow writer, Montana resident, and lifelong friend, Tom McGuane, he did a two year stint at Stony Brook SUNY campus in New York. It was a heady place in 1966, he remembers. Alfred Kazin, William Styron, author of Set This House On Fire, and Robert White, Stanford White’s grandson, were all there. Harrison decided to forgo the academic world and became a poet. He took a number of jobs to help him along the way, including working as a salesman for a book wholesaler where he talked to bookstore managers, librarians and school librarians. He learned about the publishing and book distributing business. “Most writers have no idea how publishing works,” he said. He started writing novels and novellas.

In 1960 Harrison married Linda King. The couple have two daughters, Jamie and Anna, both married and living in Park County.

“I wrote to McGuane thirty-six years ago about moving west. We spent the summer of 1968 in Livingston and the Paradise Valley. McGuane moved here that year, and we had come to Montana for our family vacation and especially for the fishing every year but one since then. I expect my daughters settled here because of their happy memories of those childhood vacations. With our children and grandchildren in Montana, Linda was keen to move here too. I miss my cabin in Michigan where I wrote for twenty-five years but I can write anywhere so we made the move.”

Anna Harrison Hjortsberg recalls growing up in Michigan. There were always animals around. The family had a pet crow called Sid. They weren’t quite sure of its sex so Sid seemed a good unisex name. Later, when she was a teenager her mother provided a sanctuary for wounded animals and orphan fawns for the Wildlife Rescue Program. Real and imaginary animals people Harrison’s life. A dog called Carla is a character in True North. “Animals are so specifically characters in my life, I grew up thinking that they were our fellow creatures. I don’t consider myself more important than a crow, or a dog. We are all in this together.”

He may miss Michigan, but there’s plenty of wildlife adventure in the Paradise Valley to hold Harrison’s interest, sometimes a surfeit of it. A couple of winters ago a pack of wolves killed twenty-eight sheep within view of the Harrison’s bedroom window and that same year, Rose, the English setter, was blinded by a rattlesnake in the yard.

Jim Harrison is best known for his novella Legends of the Fall, set in Montana, which he wrote at the age of thirty-eight. The book, which contains three novellas, was his first financial success. He told me that after years of living at poverty’s edge, Legends brought him actual money. In addition to the book sales, Hollywood bought all three novellas. Although he did not care for the movie version of Legends, shortly after its appearance he went to Los Angeles to work as a screenwriter. He found he could make enough money in two months to last for a year of novel writing.

Harrison is a man of many interests. A sportsman, and amateur naturalist, he has also written of Native American life and culture. In an essay he wrote, “Native Americans are an obsession of mine... Native Americans are like good poetry.” When I asked him how this interest came about, he replied that for thirty years he had lived close to a Chippewa Indian reservation in northern Michigan. Also, he and Linda spend their winters in southern Arizona near the Mexican border, close to Navajo country. Answering my question about Native Americans in Montana he voiced his admiration for Assiniboine poet, M. K. Smoker, who read at James Welch’s funeral in Helena.

Assessing the benefits of living in Livingston, Harrison cited Montana State University in Bozeman for its academic offerings. More important to him, he said, he can trout fish in Montana successfully for sixty days running. Sticking his Sibley bird book and binoculars in the car, he takes off for a couple of days at a time to the Big Hole, or some other favored fishing spot.

In culinary matters, Harrison disdains cuisine minceur and is inclined to look with compassion on his thin friends, Peter Matthiessen among them. “Rail lean,” he describes Matthiessen, who frequently comes to Montana for the fly fishing. On the other hand, grizzly bear authority, Doug Peacock, is “chunky,” while Harrison himself and Russell Chatham are “a tad burly.” Once the sign of wealth and position in society, “burly” has now been replaced with the lean look. There’s no chance of keeping a slender figure if you attend luncheons like the one Harrison described so tantalizingly in the New Yorker eighteen months ago: 37 courses of 17th and 18th century recipes eaten over a leisurely 11 hours and 19 minutes in luxurious French surroundings.

After the interview we repair to the kitchen to continue the conversation over a bottle of Proseco, distributed by Kermit Lynch, accompanied by delicious homemade hummus, Linda’s regular and black bean recipes, the latter with cumin, hot sauce and cayenne pepper. Cooking is a shared pleasure for the Harrisons. Their daughters keep up the family tradition. Harrison proclaims Jamie and her husband Steve “the best amateur cooks around.” He highly recommends their Moroccan lamb couscous. Jamie once worked at the epicurean Dean and Deluca emporium in New York City.

When I asked if they ate out, Jim said there are good places in Livingston so he has little need “to go over the hill (to Bozeman)” except to the airport. He then clarified that Bozeman has its share of interests, for instance, the Country Bookshelf on Main Street for books, and the Bozeman Community Coop which offers many culinary delicacies. He added that I-HO’s Korean Grill on Lincoln and Tenth is a fine place to eat.

“Writers never retire, “ Harrison noted with satisfaction. “I just write what I enjoy now. It’s a better life. Anytime I feel closed in I try something else.”

Harrison’s next book, Returning to Earth, is a sequel to his novel True North and will be published in January 2007.

~ Valerie Hemingway is a freelance writer who lives in Bozeman. She is currently celebrating publication of her illustrator son Edward’s book Hemingway and Bailey’s Bartending Guide to Great American Writers (Algonguin Books, November 2006). His caricatures of writers in the nifty guide have been highly praised. Edward’s 6 X 9 foot canvas hanging at the Leaf and Bean café on Main Street is a Bozeman landmark.

Leave a Comment Here