The Landscapes of Norman Maclean: Forest, Mountains, Water

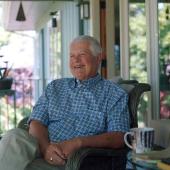

Photo by Bryan Spellman

Norman Maclean was not born in Montana, nor did he die here. His published work is slim, especially when compared to A.B. Guthrie or Ivan Doig. But I wager that if you asked people what piece of writing best exemplifies Montana, many would respond A River Runs Through It.

There are writers that we immediately associate with the peculiar regional landscapes of the Western part of the United States: Edward Abbey in the Southwest, Wallace Stegner and Wendell Berry in the Northwest, Muir or even Steinbeck in California. That Maclean is not generally thought of in the same way, that is, as a writer of the natural world, is both an advantage and a disservice. On the one hand, it highlights how A River Runs Through It is as much about the mysteries of the human heart as it is the eddies and flows of a river. But on the other, it obscures how sensitively and evocatively he was able to render the landscapes of the West.

This description of an approach to the Blackfoot manages to combine his semi-autobiographical character's subjectivity, elegant description, and swaths of geologic time:

"I had to be careful driving toward the river so I wouldn't high-center the car on a boulder and break the crankcase. The flat ended suddenly and the river was down a steep bank, blinking silver through the tres and then turning to blue by comparing itself to a red and green cliff. It was another world to see and feel, and another world of rocks. The boulders on the flat were shaped by the last ice age only eighteen or twenty thousand years ago, but the red and green precambrian rocks beside the blue water were almost from the basement of the world and time. "

Norman Maclean, born December 23rd, 1902, in Clarinda, Iowa, was just six years old when his father accepted the position of pastor at the First Presbyterian Church in Missoula, Montana. Homeschooled by his father for many years, Maclean graduated from Missoula's High School and attended Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Graduate School at the University of Chicago followed, as did a distinguished career as an English professor at that school.

During his life as an academic, he spent his summer breaks at the cabin he helped his father build on leased U.S. Forest Service land on Seeley Lake, Montana. After retirement, he would stay at the cabin until the onset of winter. After retiring in 1973, Maclean began writing for a non-academic audience. He published only one book before his death in Chicago on August 2nd, 1990. A River Runs Through It and Other Stories appeared in 1976, with a subsequent edition in 1983. The latter did not contain the "other stories" but did have a selection of photographs taken on the Big Blackfoot River by Maclean's son-in-law Joel Snyder. A 1989 edition includes illustrations by noted artist Barry Moser.

Photo by Bryan Spellman

In addition to the title story in A River Runs Through It and Other Stories are two narratives based on Maclean's summers working in the woods as a teenager. USFS 1919: The Ranger, The Cook, and The Hole in the Sky is the fictionalized account of seventeen-year-old Maclean's summer in the Selway region of Northern Idaho, the novella is divided between the time in the mountains and time spent coming out of the mountains through Blodgett Canyon. The final scene of the novella has the ranger leading a pack team back up Blodgett Canyon. Maclean, watching the team disappear, describes the scene thus:

"After a while, the sunlight itself became disembodied.

There was just nothing at all to sunlight, and the mouth of Blodgett Canyon was just nothing but a gigantic hole in the sky. 'The Big Sky,' as we say in Montana."

After Maclean's death, the University of Chicago published his unfinished manuscript about the Mann Gulch fire of 1949, Young Men and Fire (1992). Maclean's son John helped to prepare the manuscript for publication.

August 5th, 1949 proved to be a pivotal moment for the U.S. Forest Service. On that day, spotters noticed smoke in Mann Gulch, a remote area north of Montana's state capital, Helena. Forest Service Smokejumpers flew in from Missoula and landed on a steep hillside.

Within an hour, thirteen young men were dead or dying, including a ranger who had left the Smokejumpers because his mother feared that profession would kill him. Mann Gulch, then as now, was inaccessible by road. Today it lies within the Gates of the Mountains Wilderness.

The only way to access the area is by helicopter, boat, or, like the Smokejumpers, by jumping out of a plane.

Maclean visited the area repeatedly, again trying to understand this tragedy. His descriptions of the landscape show just how impossible the situation was for the young men who died in one of the worst disasters faced by the Forest Service.

Photo by Bryan Spellman

"Black Ghost," the story chosen to open Young Men and Fire, follows the 15-year-old Maclean as he fights his way through a forest fire in the Fish Creek area of western Montana. While he works in the forest northwest of Lolo Hot Springs, a fire traps him in a box canyon. He has no option but to climb the steep hillside before him.

As he struggles to breathe, trapped in smoke so heavy he can barely see, he catches sight of an apparition. At first, he thinks someone wants to help him.

Instead the black ghost slaps him hard in the face, knocking the boy back toward the flames. Fighting almost terminal exhaustion, Maclean recognizes that only he can save himself. In remembering the incident, he knows he must tell the story of the young men trapped and killed by the Mann Gulch fire of 1949.

Later, Maclean and his brother-in-law drive back to a portion of the woods left to burn by the fire crew, who knew that the fire wouldn't be able to jump the lines again. His description of the inferno is nightmarish, surreal, even expressionist:

"It was a world of still-warm ashes that had incubated once-hot holes. The black poles looked as if they had been born of the grey ashes as the result of some vast effort at sexual intercourse at the edges of the afterlife. When the vast effort was over, it was discovered that the poles were born dead and the ashes themselves lived only because the winds moved them.

Photo by Bryan Spellman

Another posthumous publication, The Norman Maclean Reader, followed in 2008. This collection includes the five chapters of an unfinished manuscript looking at the tragedies of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, or Custer's Last Stand, as Maclean referred to it.

Maclean had been attempting to write about Custer beginning in 1959. The story grabbed Maclean's imagination, and he brought his academic and personal interests into play as he attempted to make sense of that tragedy. His love of Montana's landscape comes through clearly in his writing. Maclean describes "Custer's Hill" thus:

"It is close to a finished composition--- a hilltop in a big sky; repeating the circle of the hilltop, a circle of kneeling men in blue; within the embattled circle a central figure highlighted by blonde hair; and, surrounding the circle of blue, larger circles of contrasting redskins."

Forgiving the admittedly archaic use of "redskins," we find that the three colors described, red, blue and blonde, more than resemble the colors of the flag: in his hands, Custer's folly becomes the story of America.

He follows that passage with an interesting point: "The battle has also the power to promote business, draw customers and sell beer. And it has two powers perhaps deeper than the others - the power of horror and of jest."

So, we return to where we started. Maclean's most famous description of a landscape, and the one from which this issue derives its title, are the final words of A River Runs Through It. With this passage, the Blackfoot becomes more than a mere river, however beautiful, but a poetic statement once again combining geologic time with the universal experience of love and loss. They recall the final words of The Great Gatsby, in which Fitzgerald compares being alive to "boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past," but perhaps even more beautiful and more wise:

"Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world's great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs.

I am haunted by waters."

Photo by Bryan Spellman

Leave a Comment Here