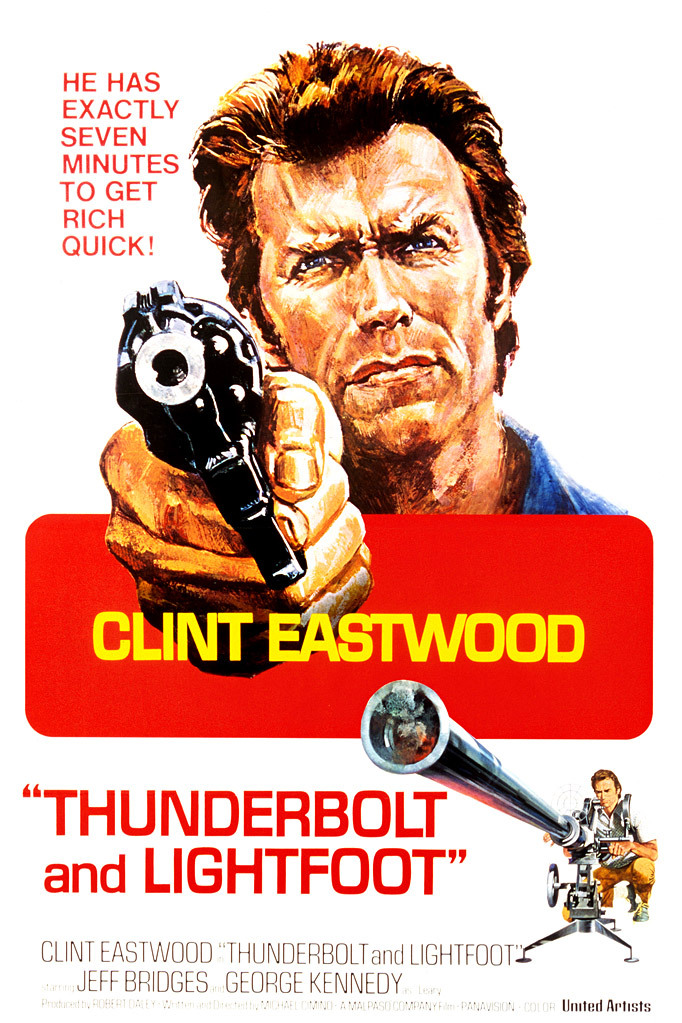

Montana Media: The 50th Anniversary of Thunderbolt and Lightfoot

Hollywood in the 1970 was an era characterized by a vogue for gritty realism, jacked-up rebellion (often unsuccessful), fast cars, and Clint Eastwood. Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, released in 1974, has all of it, and Montana. Fittingly for a picture styling itself as a “contemporary” Western, it was shot entirely on location in the Treasure State, specifically in Great Falls and the surrounding region. In commercial terms it was a modest though not spectacular success (something Eastwood blamed on the ad campaign from United Artists), but in the years since its release it has achieved an appreciative cult following. The movie’s appeal is three-fold: the buddy comedy chemistry between the two leads, the chaotically exciting car chase sequences, and the unique flavor granted by its authentic Western locations. On the fiftieth anniversary of its release, it’s worthwhile to turn an eye toward said locations.

The plot centers around two outlaws, Thunderbolt (Clint Eastwood), an experienced bank robber turned occasional preacher, and Lightfoot (Jeff Bridges), a footloose young drifter who just can’t fit into regular life (Bridges’ role in Rancho Deluxe the following year feels like a continuation of Lightfoot in many ways). They meet by accident during a car theft and find themselves teaming up largely due to convenience before taking a liking to each other’s company. Thunderbolt is trying to escape from his former partners in crime, Red (George Kennedy) and Eddie (Geoffrey Lewis), but they want the hidden loot from a successful bank robbery he stashed but never claimed. Unable to simply go to the cache, a one-room schoolhouse that was subsequently relocated, a new bank job is offered. Will the job go off without a hitch and will Thunderbolt and Lightfoot ride off into the sunset?

The setting for the new bank job is the fictional town of Warsaw (subliminally designed to suggest “Wilsall,” perhaps?). The locations for the town freeway sign and the Warsaw elementary school were, in a fine little bit of Montana movie symmetry, filmed on the 7-Bar-9 ranch, which at one time was owned by Gary Cooper’s father, Montana Supreme Court Justice Charles H. Cooper. The 7-Bar-9 is alongside the Missouri River, which makes a few appearances in the film itself, although the script amusingly suggests that it is the Snake River. Many Montana residents will recognize the Gates of the Mountains in the scene where Thunderbolt and Lightfoot make a break for it on a river boat; the serene majesty around them makes for a great moment of reprieve before the criminal action kicks into gear again.

While a fictional town has the spotlight, the film also provides the poignant bit of movie magic that is showcasing real places that no longer exist. The church where Thunderbolt preaches at the beginning of the film (Eastwood would dip back into the outlaw preacher well again eleven years later with Pale Rider) was St. John’s Lutheran Church in Hobson, Montana. It was sold and dismantled in 1980; there was discussion of relocating it to Troy, but this plan never achieved fruition. Similarly, the business where Lightfoot gets employment before the heist is Pinski Bros. Plumbing and Heating, which was an actual business in Great Falls, one that had been a fixture in the community for several years. One of the most crucial locations, the drive-in movie theater where the bank robbers hide out after the job, was provided by Great Falls’ 10th Ave Drive-In. It closed for the end of the season just after filming wrapped on Thunderbolt and Lightfoot; it re-opened the following June, only to shut down for good two months later.

The universe offered similar capriciousness toward the vital one-room schoolhouse that figures in the film’s climax. It was a constructed set, modeled on an actual one-room schoolhouse located in Ravalli, Lake County, near Highway 93. After the shoot, the replica schoolhouse was purchased by a developer and relocated to Dearborn Meadows to serve as a tourist attraction, but it was purchased again in 1974 and reconverted into a bar, rechristened Earl Smith’s 7-Bar-9 Saloon. It opened for business in 1975 but burned down in a fire a year later. While an aura of bad luck seemed to befall some of the location sites, such misfortune didn’t permeate to the rest of the production.

The secret weapon to the film’s success is Jeff Bridges. Apparently Eastwood expressed concern during production that he was being upstaged by Bridges; it is true that Lightfoot gets most of the humorous and playful moments, but Eastwood’s concerns were misplaced (although it is true that Bridges did receive an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor for the film). The dynamic between the grim mentor and the goofy apprentice is one of the main reasons why the film works and stands out among similar buddy-road movies of the same era.

The film was the directorial debut of Michael Cimino. He had co-written the scripts for Silent Running (1972) and Magnum Force (1973), the sequel to Dirty Harry (1971). He wrote Thunderbolt and Lightfoot as a spec script with Clint Eastwood in mind. Eastwood apparently liked the property so much that he wanted to direct it himself, but ultimately he granted the opportunity to Cimino instead. Cimino would later state that he owed his filmmaking career to Clint Eastwood. Four years later Cimino scored massive commercial and critical success with his grim Vietnam war epic The Deer Hunter, which won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director for Cimino. Alas, meteoric success precipitated meteoric catastrophe; Cimino’s follow-up passion project, Heaven’s Gate (1980) was a failure that nearly bankrupted the production company United Artists. While Cimino did direct a few films afterward, he never achieved the same level of prestige or success. There is a kind of ironic symmetry in that the film that launched Cimino’s directing career and the film that tanked it were both filmed in Montana, as well as that, for all the hopes of grand significance the Western historical epic was meant to carry, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot has emerged, fifty years down the road, as the more successful picture.

Leave a Comment Here