The First Signal

Ed Craney and the Broadcast History of Montana

On the evening of August 14, 1953, several young boys stood in front of an appliance store in Butte, Montana, their eyes transfixed on something displayed in the store window. At the same time, not far across town on the second floor of Frank Reardon's Pay-N-Save Supermarket on Harrison Avenue, a man named Ed Craney—the same man who first brought radio to Montana—was fine-tuning the dial on some piece of electronic hardware. After final calibrations were made, Craney gave the signal to his small crew to send the signal.

Back in town, the faces of the young boys gathered around the shop window took on a pale, bluish glow. They watched as a ghostly image materialized right before their eyes on the 17-inch RCA television screen. It wasn't a show or a commercial or anything approaching programming as we would know it today, but a simple test pattern that Craney had broadcasted from just down the street—a monochromatic pattern of lines and geometric shapes over which a Native American chief's head in full headdress was superimposed. This test signal first broadcasted from a room above a supermarket on Harrison Avenue would soon be beamed into living rooms around the state—from Butte to Billings, Missoula to Miles City, and beyond. Montana would finally join millions of other living rooms across America—and it would never look the same again.

Montana's Don Draper

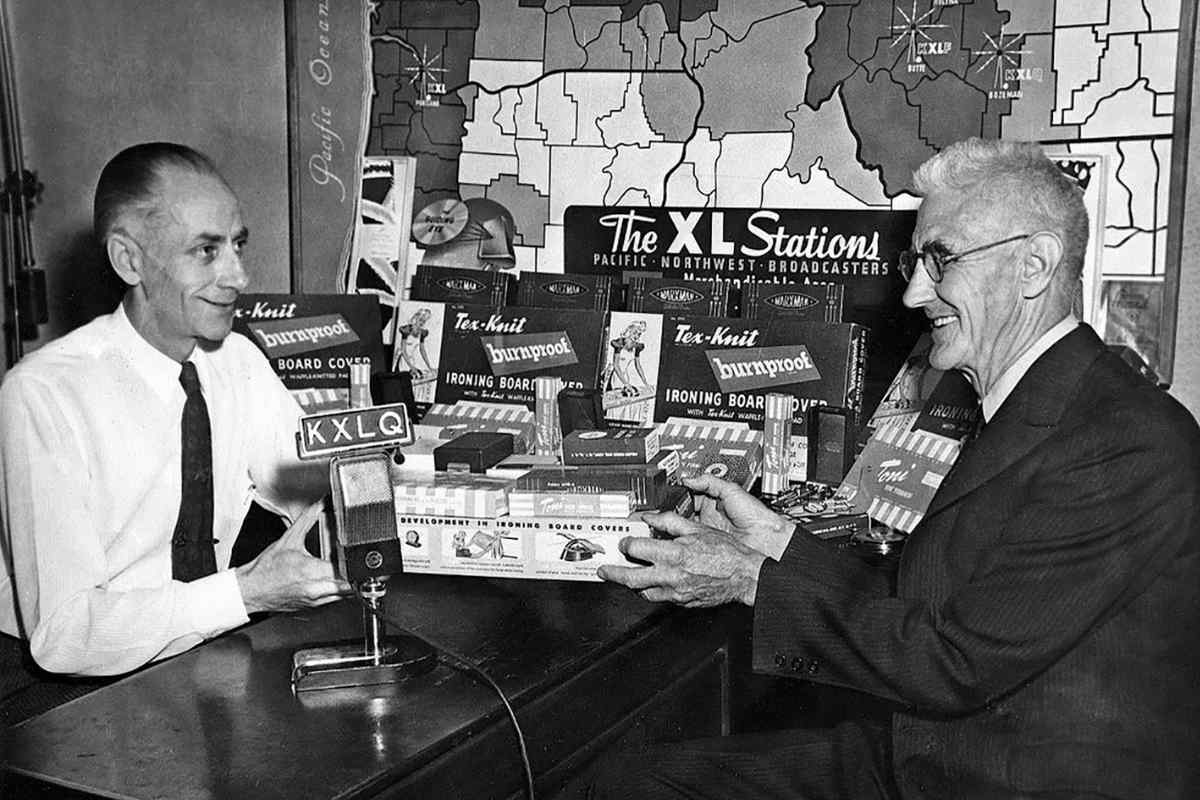

In photographs dating from the 1940s and 1950s archived by the Montana Historical Society, Craney appears very much the businessman and salesman of his era. He has on a starch-white shirt underneath a double-breasted suit, a tie knotted to his throat; wire-rimmed glasses appear snug against his face, through eyes half-squinting, as though he's constantly sizing up others; his hair perfectly parted and gelled solid to one side, without a strand out of place. The rest of Craney—in both style and substance of his era—is easy for us to imagine because this image of Craney is drawn from the same medium, television, that he brought to Montana. Someone like Don Draper, maybe, of Mad Men.

Edmund "Ed" Craney was born on February 19, 1905 in Spokane, Washington to a schoolteacher mother and a father who worked for the railroad. Even at an early age, Craney was obsessed by broadcast radio. He built Spokane's first radio transmitter and went live on October 18, 1922, creating the city's first radio station in the process.

In Scott Parini's Ed Craney: The Voice of Montana, Parini interviews Shag Miller, who called Craney a "superb" businessman, but also went on to describe Craney as something of an enigma who "would do anything for you, but also cut your heart out." According to Miller, even back when Craney was in radio, he had his own way of pulling in advertisers to fill out his programming slots. It wasn't unheard of for ad reps—the other Don Drapers of Craney's orbit—to come to client meetings at his office and encounter a full spread of caviar, Danish hams, cheeses, and imported liquor. He would also send gifts to his important clients in big cities like Chicago and New York—copper jewelry and Flathead cherries, of course—to remind them, and the advertisers they worked for, of Craney's generosity that time they visited Montana. Subtlety wasn't part of Craney's playbook. But he also understood that Montana was a unique market for advertisers, whether in radio or television, as he recalled to an interviewer in 1977: "It is a high cost market and one that is difficult to get national advertisers to come into…because there just aren't the people in Montana to make it a market." As it turned out for Craney, it was far easier to flip a switch and send a signal from one Montana town to another than it was to convince ad men and television executives why the the rest of the country should send its signal to Montana.

The Ghost in the Glass

Imagine a map of Montana at night in 1953, shortly before the era of broadcast television—the ridges of the Bitterroot Range sweeping down into the dark valley and rising again toward the Sapphires; no interstate freeways, just unlit squiggles of two-lane roads and gravel turnouts threading small towns together. Places along the Hi-Line with names like Havre, Cut Bank, Malta, Glasgow—names that meant nothing to passengers aboard the Empire Builder as it chugged west from Chicago to Seattle while everyone slept. Imagine then, one evening in August, a blue blip appearing over Butte—a test signal lighting up one dark corner of the map. Soon, nearby Missoula and Helena receive the signal, and two more blips come on and join the first. Before long, the signal is relayed to Great Falls and Billings, and the blips come faster, brighter, and get boosted all the way to Havre, Cut Bank, Malta, Glasgow—to all the towns dotting the Hi-Line until the dark map becomes a constellation of stars. Suddenly, Montana begins to take on that eerie, bluish glow that only a television screen at night can cast—and huddled in living rooms across the state, families who have never been to places like Pasadena or Pittsburgh are now joining the rest of America in its latest obsessions: "I Love Lucy" and "The Lone Ranger."

And this signal that lights up the dark map is much stranger and more intimate than any signal before it. At a time when radio cowboy shows still aired, when newsboys still shouted from street corners, and cinemas had, for decades, projected sound and moving images onto a screen—what made television different was its illusion of presence, how immediate and intimate it made images of people and the rest of the world feel. You could listen to the radio in your kitchen or while driving your car and imagine the story, or read yesterday's news about some tragedy happening half a world away, or watch an old movie in a theater with an ending you've heard talked about—but television showed you exactly what everyone else was seeing that night in Pasadena or Pittsburgh or Plentywood. You didn't have to imagine the Lone Ranger and his horse, Silver, galloping toward some dusty town like you did on the radio—or wait months to see its ending flicker across a big screen years after someone else already had. It was happening right now, in your living room, on your television screen, the same thing every other kid in America was seeing.

Once television entered fully into its own—going live, in color—you could watch a president address the nation in real time, his gaze meeting yours through the screen to earn your trust and future vote. Instead of hearing about it on the radio or reading it in the dailies, you could watch the same president—or his brother even—get assassinated in your living room, over and over, on the evening news. One night, a preacher might deliver you a poignant sermon, wipe away tears, then ask you for money for your own salvation; the next, you might see a man planting a flag on the moon. The moon! And maybe on some other night, it's a war unfolding around you, one that feels as visceral as it does unreal, the sound of artillery filling your living room, right around the time your family is ready to sit down for dinner.

But it's usually on the most ordinary nights that the signal feels strongest: a sitcom family you wish were yours, sitting on a sitcom couch you can't afford, where any problem—no matter how large or small—can be solved in under thirty minutes. And when this family makes you laugh, it's in the same way, you understand, that it makes a stranger in Pittsburgh or Plentywood laugh. Or you're a nine-year-old and waiting, giddy with your toy six-shooters ready at the hip, for that moment you know is coming: the black-masked Lone Ranger rearing Silver and calling out to millions of young fans through the screen, "Hi yo, Silver, away!"

The fact that Montanans could watch "I Love Lucy" or "The Lone Ranger" at the same time as strangers from New Jersey or California wasn't what made it special. What did make it special was that for twenty-three minutes (plus commercial breaks, of course), Lucy and the Lone Ranger didn't just appear in Montana living rooms—their iconography embodied the American experience. This meant that they belonged to Montanans, too.

Testimony & Transmission

Craney's big Mad Men moment didn't happen on a television set, but in front of a Senate committee in 1959. By then, he had already deployed a patchwork of boosters and single-watt translators across the Tri-State region—Montana, Idaho, Wyoming—bringing television to rural places that were so remote they didn't even have reliable roads, let alone broadcast towers. The only problem: his one-watt translators, while low-powered and localized, sometimes caused interference with national broadcasts, a possible violation of Section 301 of the Communications Act of 1934. This became a concern not just for the FCC, but for congressmen representing more populous states and the powerful broadcast lobbies that influenced them.

In the first season's finale of Mad Men, titled "The Wheel," Don Draper pitches Kodak's new slide projector to a room of stone-faced executives. As the lights dim and the machine begins to whir, still images from Draper's own life flicker on the screen—moments captured when he was a younger man, a more attentive father to his children, Bobby and Sally; a more devoted husband to his young wife, Betty. This is Draper's now-famous pitch: he's not selling Kodak's round slide projector as a piece of new technology, but as something else entirely—a machine of nostalgia, a way to return and revisit that "twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone."

Craney wasn't pitching for Kodak when he stood before those stone-faced congressmen. He wasn't trying to sell a slightly newer model slide projector or even the idea of nostalgia. He wasn't selling one-watt translators, or television programming. What he offered was something far more powerful: a vision of America itself—the belief that isolated families and communities scattered across the mountainous West were just as much a part of the American story unfolding nightly on television as those living in Chicago or New York.

In July 1960, less than a year after Craney's Senate testimony, Congress passed Public Law 86-609, amending the Communications Act to authorize the FCC to license the one-watt translators Craney and others had already been deploying across Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana.

The Sign-Off

It's no small irony that Ed Craney—the man who lit up Montana's map and brought it into the broadcast age, who gave the state its first taste of the visual language of American iconography—would, in the end, watch his own world dim as he slowly lost his sight to macular degeneration. The same man who once invited ad reps to a meeting catered with caviar and Danish hams only to tell the ad men later to "get off your ass and get out there," was also the man who, in 1948, formed the Charles Russell Memorial Committee to buy back a collection of Russell paintings about to be sold and shipped to the East Coast. Later, he created the Greater Montana Foundation, which still funds programming and scholarships in television and broadcast journalism today.

Even as his vision faded, Craney paid people to read him the newspaper at his Nissler Junction home, so he could keep up with what was happening in the world. When his health declined further and he could no longer communicate, he was moved to a nursing home in Montpelier, Idaho, where he died on March 6, 1991. In the end, Craney wasn't a man who felt his life needed to be celebrated. Without any pomp or circumstance—and it most definitely wasn't televised—his final request, honored by those who knew him, was that no funeral or memorial be held in his name.

So maybe the most fitting thing we can say about Ed Craney isn't written on a plaque, or a foundation that bears his name, or even found in the fine print of a Senate committee hearing—but in those boys still standing outside the appliance store on Harrison Avenue in Butte, unaware that just down the street, above Frank Reardon's Pay-N-Save Supermarket, a man was about to send the signal that would change Montana forever. They watched as a monochromatic test pattern flickered to life on the screen—geometric shapes and lines appeared, the ghostly glow of a Native American chief in full headdress. For that brief moment, they weren't in Butte at all, but maybe somewhere inside the signal itself, and part of something much larger than even they could understand, something that was happening everywhere all at once, and this would change their lives as they knew it.

Leave a Comment Here