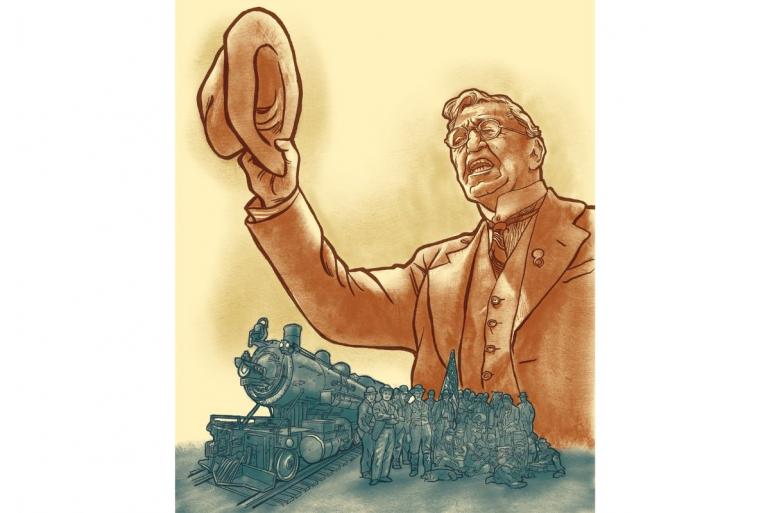

Hogan's Army Heads East

How a Butte Miner Hijacked a Northern Pacific Train and Tried to Drive It to Washington D.C.

In the America of 1894, economic uncertainty and political division ruled the day.

The Great Panic of 1893 had spilled over into the proceeding year. Wheat prices had fallen through the floor and into the cellar. Likewise, the price of silver, artificially buoyed by the Sherman Silver Purchase Act for years, was now tanking following the act's repeal. The silver mining burg of Granite became a ghost town overnight. Many of the railroads, judged too big to fail, were in receivership. In New York, some 200,000 were without work. In Chicago, 100,000. And even in the sparsely populated backwater of Montana, the number reached as high as 20,000 souls without employment.

Across the nation, thousands were unemployed and unhappy. The Populists, a left-wing party mainly comprised of poor Southern sharecroppers and disenfranchised wheat farmers from out West, managed to carry several states in the general election.

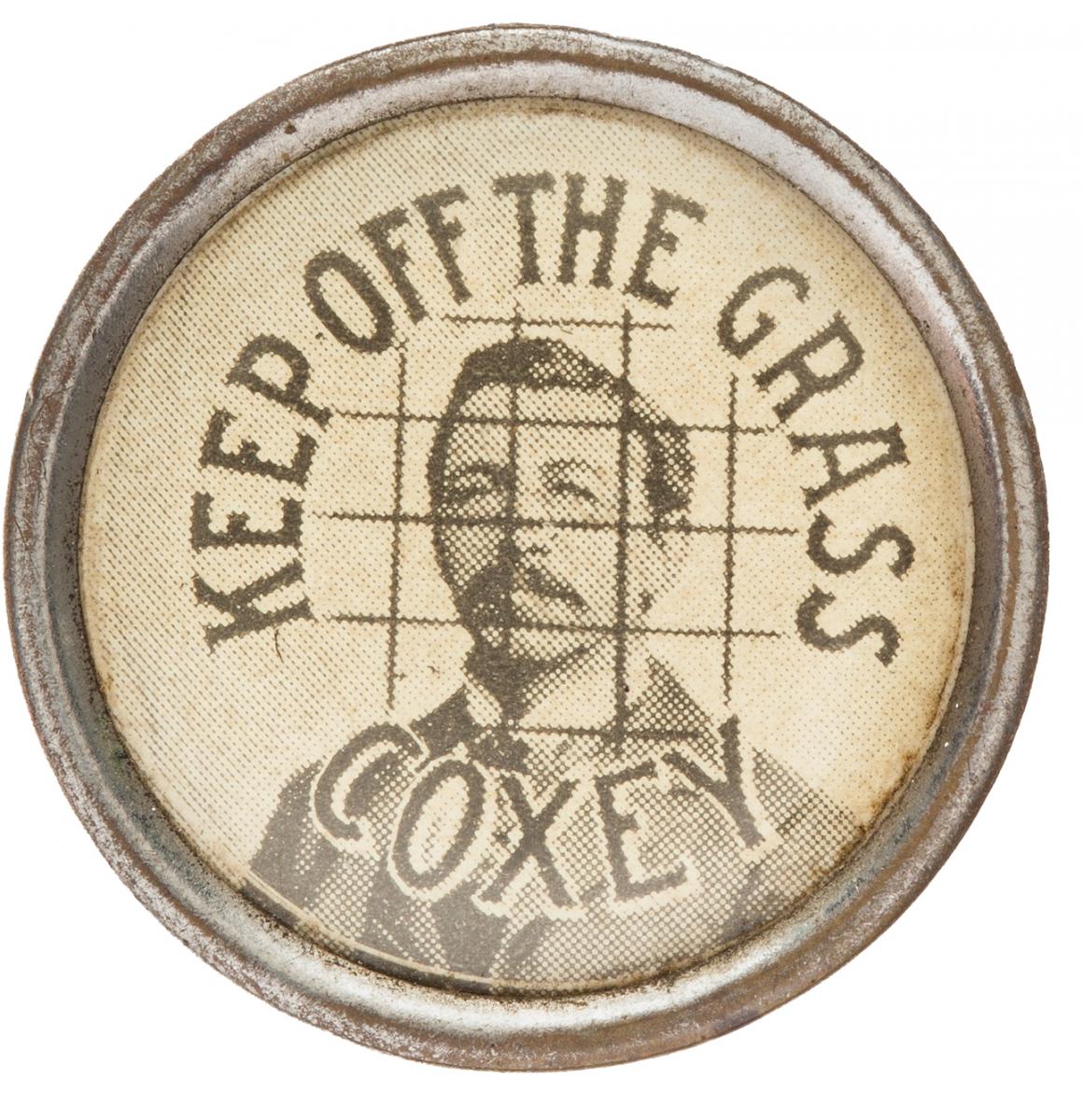

One ambitious party member named Jacob S. Coxey had a radical notion. He thought that the federal government should create jobs for the mass of recently unemployed workers. The nation's infrastructure, he argued, was rapidly deteriorating. All of those laborers might be profitably put to use paving roads and building other public works. But he didn't want to spend years trying to win grassroots elections; he had something rather more direct in mind.

He raised an army. At first, it was around 500 men, but some estimates place the number of participants across the United States as high as some 60,000 men and women.

If they marched on Washington, D.C., Coxey reasoned, the federal government would have to meet the workers' demands, and probably with more expediency than through traditional political action. So in March of 1894, Coxey's Army set out for Washington.

The spirit of Coxeyism, meanwhile, went West. All over the country, groups of the out-of-work devised novel ways to head for the capital. The writers Jack London and Ambrose Bierce, sympathetic to the cause, joined local groups of Coxey's Army. Bierce, for his part, derided that the status quo had become a "pickpocket civilization," with the rich picking the pockets of the laborers.

But not everyone was quite as taken with Coxey's radical politics.

It's easy to imagine how concerning this was to those who felt that an army of vagrants bullying the country into capitulation was less than democratic. The Tacoma News, for one, lamented that "Coxeyism teaches a bad lesson, the most dangerous lesson indeed that can be taught to the American people—the lesson of dependence on the federal government." And as author Philip Dray points out, it must have been especially galling to those who agreed with the Tacoma News that the movement had caught on in "the West, the part of the country long identified with the creed of individual reward won through determination and hard work."

Even so, Coxey found many willing followers in Montana. One of them was a teamster named William Hogan. Hogan considered himself a general in the service of Coxey's Army, and a good one too. For one, he was responsible for recruiting some 500 "soldiers."

Hogan had a plan that made Coxey's march on D.C. look like a daisy chain. He figured his army had more ground to cover, and he knew that a march from Montana would end with most of them freezing to death somewhere in North Dakota.

Walking was for suckers; General Hogan would steal a train.

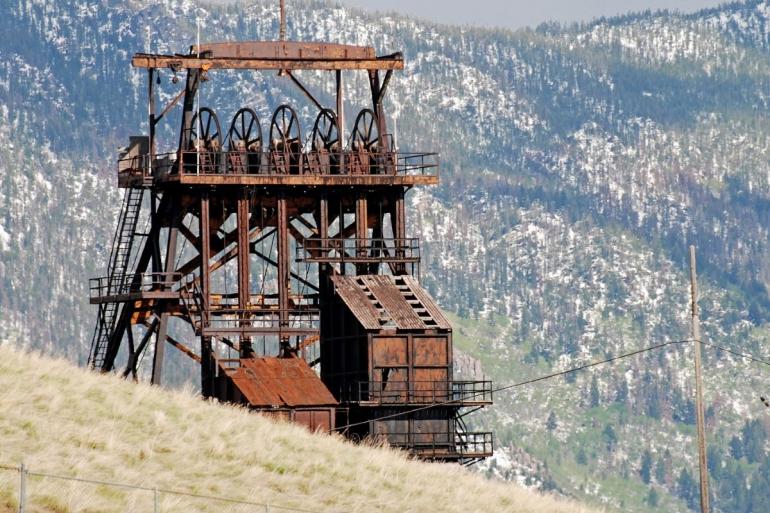

Although given the apparent indifference of the local authorities, he might not have considered it theft. As a matter of fact, Hogan was a smart man and well-connected. He knew that if he effected his quest through violence, he would lose the support of the people. Though infamously violent skirmishes between mine owners and laborers would occur in the next twenty-five years, this was the farthest thing from one of them. Copper barons William Clark and Marcus Daley, not historically known for their pro-labor views, were on the side of Hogan's branch of Coxey's Army; they, too, supported the reinstatement of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and the continued coinage of silver at 16-to-1. They owned mines, after all. And Butte was a mining town; those who lived there lived to mine.

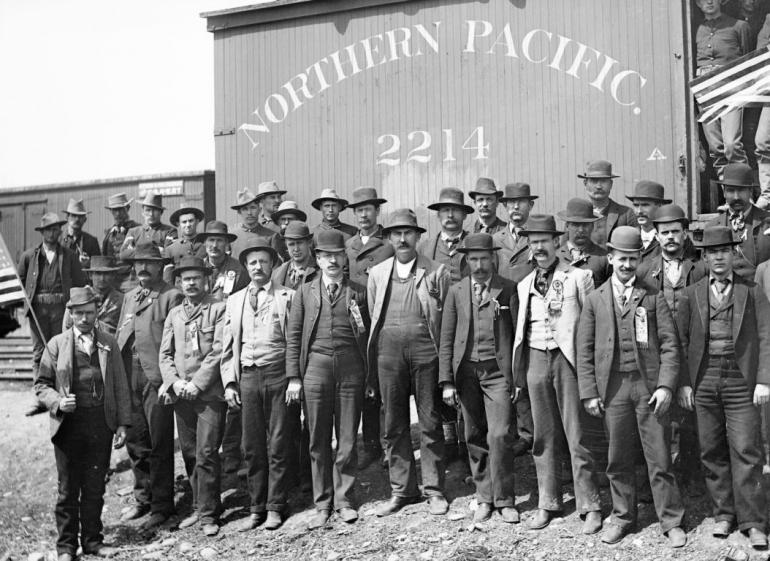

So Hogan didn't exactly hijack the train with his band of pirates. He did the next best thing, meeting with the mayor and county commissioners and asking them to help him enlist the support of the Northern Pacific, which was itself bankrupt and in receivership. N.P. executives might have winked at or even condoned Hogan's mission, but the company's new stewards, tasked with keeping the business on track, decided against the request. Instead, they leaned on a judge to issue an injunction against Hogan and his followers so that anyone commandeering the train would be in contempt of court.

The town of Butte, meanwhile, materially supported Hogan and his hundreds of followers through donations of food and clothing.

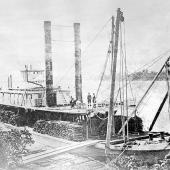

On April 19, Hogan and his men marched from their camp on the so-called Flats into the Northern Pacific trainyard. But there weren't enough cars in the shop to carry the army to D.C. The mob retreated to their camp and resumed waiting. Then, in the early morning of the 24th, some of Hogan's men snuck into the railyard and attached six coal cars and a box car to Engine #542. They started the train and moved it adjacent to the camp, where the rest of Hogan's men boarded. As they set off, stations to the east got word: make way for an unscheduled "wild train" coming through.

Engine #542 arrived in Bozeman at around 5:30, just as dawn was streaking the sky. It must have been chilly, but that didn't stop a crowd of supporters from assembling to receive Hogan's Coxeyites. In Bozeman, coal cars were dropped in favor of additional box cars, including one full of food and drink donated by sympathetic Bozeman folk. As the train pulled out, hundreds cheered them on.

An incidental tunnel cave-in later arrested their progress, but they arrived at Livingston by the late afternoon to find another ebullient crowd who pressed more blankets, food, and clothes on the men. Someone gave a speech, and the train continued eastward.

They found more trouble east of the track—a Northern Pacific superintendent named Charles Finn had received word they were coming and dynamited a rock slide onto the track to slow them down. Hogan and his men removed the rock pile, moved just past, and then put the rock pile back to slow their own pursuers. When they ran out of water for the steam engine, men with buckets walked down the Yellowstone River and filled them, hand over hand, until they had enough to go on.

Meanwhile, U.S. Marshall William McDermott was assembling a posse out of those few able-bodied Butte men who didn't support Hogan. The result was a party of eighty men. By the time they got to the edge of town, fifteen of them had turned around and gone home. Those who remained to chase after Hogan were, according to one local paper, "the scum of Butte."

All that scum, along with Deputy Marshall M. J. Haley, boarded another train and bore east with the idea of catching up to Hogan and stopping him.

But Hogan arrived in Billings to the biggest crowd of supporters yet. Some 500 people surrounded the train with, according to author Dave Walter, "400 pounds of beef, 250 loaves of bread, and 400 pounds of potatoes" for the Coxeyites. But Haley had caught up as well, going before the assembled crowd and demanding their surrender. One of Haley's deputies fired his rifle —we don't know whether there was provocation or no—and the crowd erupted into bedlam. Another thirty or so rounds were fired, striking a few of the Coxeyites. One errant shot killed an innocent Billings tin worker named Charles Hardy. The crowd responded by taking the men's rifles and smashing them against the train tracks while Haley and his men attempted to retreat to the safety of their train. Hogan told the crowd not to pursue the lawmen—further violence wouldn't do any good. Billings officials, for their part, held ten of the deputized "scum" for the wrongful death of Hardy.

That night, they finally stopped Hogan's train. The same judge who had issued the injunction against the hijackers now petitioned President Grover Cleveland to use federal power to stop the Coxeyites. Cleveland consented, calling up troops from Fort Keogh to move to Forsyth and stop the men by any means necessary. Hogan's train had arrived at Forsyth earlier to resupply and rest. Hogan, no doubt considering the bloodshed that had erupted at the Billings station, telegraphed the authorities that he and his "army" had no intention of resisting if met by troops. After receiving that communique, Northern Pacific superintendent telegraphed the Forsyth yard to see if the train was still there. It was. Six companies of the Twenty-Second U.S. Infantry loaded onto a Northern Pacific special and sped to Forsyth.

True to his word, Hogan surrendered to the real Army on April 26. Hundreds of his followers were rounded up, even as many others jumped off of the train and scattered for whatever cover they could find. An inventory of their effects noted that there were only three firearms among all the men, and the only one that worked was a mere .22 caliber. One state newspaper stated that, among the men, "forty-three copies of the Bible were found. The Army didn't seem to be composed of such desperate characters after all."

Hogan would serve six months in Deer Lodge for his stunt, but his brief celebrity didn't do too much to destroy his career; in 1895, Anaconda Mining Company records show he was back at the Moulton mine, again working as a teamster.

Hogan would serve six months in Deer Lodge for his stunt, but his brief celebrity didn't do too much to destroy his career; in 1895, Anaconda Mining Company records show he was back at the Moulton mine, again working as a teamster.

As for Coxey himself, he finally reached D.C. with some of his men. They camped outside the city for a while, but public interest had begun to dwindle for the movement.

By the time he came to be on the lawn of the Capitol, he managed to give a speech and was arrested for walking on the grass.

Yet, a few short decades later, most of his ideas would be enacted by a federal government searching for ways to alleviate the effects of the Great Depression.

As for Butte, silver was forgotten in favor of copper, enormous quantities of which were suddenly needed to wire a nation for electricity. The misadventure of Hogan's army faded into memory. Twentieth-century clashes between labor and capital in Butte would likely involve bombings, shootings, or lynchings rather than anything as prosaic as steam trains.

But there must have been those who, as late as the 1960s or 1970s, still remembered standing on the platform, waving and cheering as Engine #542 set off on its quixotic, ill-fated journey east

Leave a Comment Here