Full Steam Ahead

A small group of volunteers works to restore a vintage steam locomotive in Missoula that once worked in logging camps and even starred in a Hollywood film

All across the United States, there are hundreds of old steam locomotives on display at museums, historical sites, and city parks. To most people, these relics look like a boiler atop big wheels covered in an intricate web of pipes, rods, domes, and more. While they are interesting to look at, it can be hard to see these masses as anything more than cold, hard, lifeless steel.

But for people like Larry Ingold, a steam locomotive is a living, breathing machine—the closest thing humans have ever made to a machine that actually feels alive. That's why he's spent his entire career working with them and why he's excited to lead a small group of volunteers breathing new life into an old steam locomotive on display at the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula.

The steam locomotive dates back to 19th-century England, and the way it works is relatively simple: Using fire, the locomotive boils water to produce pressurized steam in a boiler, which is pumped into cylinders and used to push rods. These rods then turn large wheels, propelling the locomotive (and usually the cars behind it) forward. The steam locomotive played a key role in powering the industrial revolution in the late 19th century but fell out of favor by the mid-20th century, replaced by internal combustion diesel engines that were (relatively) cleaner to operate and easier to maintain. While most of Montana's railroads stopped using steam locomotives in the 1950s, a few restored engines have appeared on the state's rail lines since then. In September 1971, perhaps the world's most famous steam locomotive, the London & North Eastern Railway 4472 "The Flying Scotsman," traveled across the Hi Line as part of a nationwide tour. In the 2000s, two big steam locomotives owned by the City of Portland, Oregon, visited on special excursions—one built for the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway in 1938 and another for the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1941. Most recently, a 2-8-2 type engine built in 1914 was brought to Butte in November 2024 as part of a shoot for the "Yellowstone" spin-off "1923."

Aside from those visits, and a narrow gauge locomotive that operated near Virginia City until the 2010s, seeing a living and breathing steam locomotive in Montana has been about as rare as finding a parking spot at Logan Pass in July.

Of course, there are many different steam locomotives on display across Montana; from a large 4-8-4 type in Havre that once led trains for the Great Northern Railway to a small two-truck "Shay" type in Columbia Falls that once helped drag logs out of the forests of northwest Montana. In total, there are about two dozen steam locomotives of various sizes throughout Big Sky Country. Among them is Locomotive No. 7.

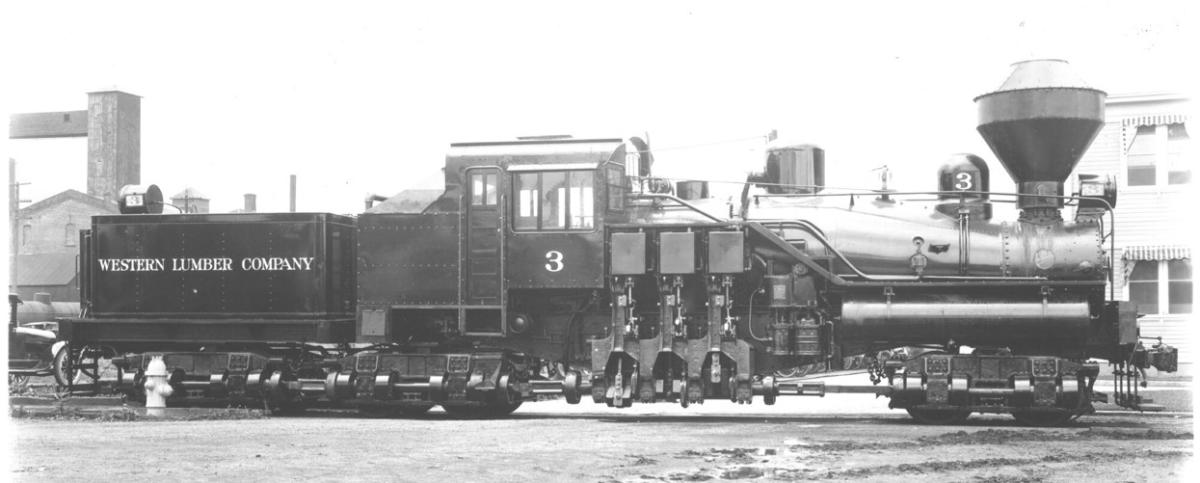

Locomotive No. 7 was a 70-ton, three-truck geared locomotive built by the Willamette Iron & Steel Works in Portland, Oregon, in 1923. It was specifically designed to haul heavy loads on poorly built tracks, which was common on temporarily constructed logging railroads. Instead of having a long series of rods moving three or four large sets of wheels, these locomotives had complex vertical cylinders that powered smaller wheels through geared connections. The locomotives were known as "Shays" because they were designed by a locomotive builder named Ephraim Shay. For decades, the locomotives were built exclusively by the Lima Locomotive Works in Ohio, but when the patents for the Shay-type locomotive expired in the 1920s, the Willamette Company seized the opportunity to build the engines, even hiring one of Lima's top designers.

In the 1920s, the Western Lumber Company was looking to purchase a new steam engine to move logs through the woods and, perhaps because Portland was much closer than Ohio, they decided to buy from Willamette. In 1923, No. 7 was built in Portland and headed east to a logging camp near Arlee. In 1930, after the Arlee logging project had come to an end, engine No. 7 was relocated to the Blackfoot River Valley, east of Missoula. By then, it and the other assets of the Western Lumber Company had been acquired by the Anaconda Company. The locomotive would spend the next 20 or so years moving logs down the valley to the mill at Bonner. In the late 1950s, as trucks began to replace steam locomotives at logging camps, locomotive No. 7 was placed in storage at the mill in Bonner, just in case the new equipment broke down.

In 1954, Hollywood came calling when Republic Pictures went to Montana to film the Western Timberjack, starring Sterling Hayden, Vera Ralston, David Brian, and locomotive No. 7. The movie, based on a book written by a University of Montana graduate, was about a rivalry between two logging camps that turns bloody. The studio had No. 7 repaired and put back into service so it could be used in several scenes. Since the Anaconda's own logging rail lines had been ripped up, the studio filmed the locomotive on track owned by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific, better known as the Milwaukee Road.

Timberjack was released in 1955. After filming, the locomotive was displayed in front of the lumber mill in Bonner, where it remained for the next 30 years. In 1987, the lumber company donated the locomotive to the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula, where Larry Ingold discovered it a few years ago.

Before moving to Montana, Ingold worked for the Sierra Railroad in California, where he did everything from rebuilding track to operating steam engines. After retiring about a decade ago, Ingold settled in the Bitterroot Valley, where he took on various house projects and worked on a 7.5-inch gauge replica of a big Southern Pacific steam locomotive. But eventually, that wasn't enough to pass the time.

"My wife told me that I needed a project to stay busy, and I think she meant for me to paint the bathroom or fix the railings on the back porch," he said. "But instead, I began restoring a full-size steam locomotive."

Ingold approached the museum a few years ago about giving the locomotive a fresh coat of paint and sprucing it up. But as he and a small group of volunteers began working on the project, they realized the locomotive — despite being stored outside for decades — was still in good shape. Most notably, it was only missing a few small pieces. That's when Ingold realized that it might be possible to make the locomotive run again. Over the last few years, Ingold and his crew have taken everything apart, cleaned it up, and made repairs when necessary. They are also working with a contractor to repair the boiler (something that has to be done by certified professionals with what is called an "R Stamp").

Ingold said a number of old-timers claimed that there were issues with the locomotive that would permanently render it inoperable. But so far, those have just been old rumors, and there's nothing stopping them from completing a full restoration.

Having been involved with numerous steam locomotive restorations over the years, Ingold said such projects can take years, so he's not providing a specific timeline for when people will see the locomotive run. However, he's confident it will happen within the next few years. Currently, there is a short stretch of track at the museum for the engine to be moved on, and if successful, Ingold said he hopes they can build more track for a longer run. The group has already constructed a shelter over the locomotive to protect it and the volunteers working on it from the elements.

If locomotive No. 7 runs again, it will be the only operating steam locomotive in Montana. However, it isn't the only locomotive rebuild project currently underway. In Libby, a small group of volunteers is working on rebuilding another logging locomotive that once worked for the J. Neils Logging Company.

Ingold said he's looking forward to showing people what a real live steam locomotive looks like.

"People just love that we're doing this," he said.

- Reply

Permalink