The Sage Wall Goes Viral

The mysterious formation at the intersection of internet culture, alternative archaeology, and Montana tourism...

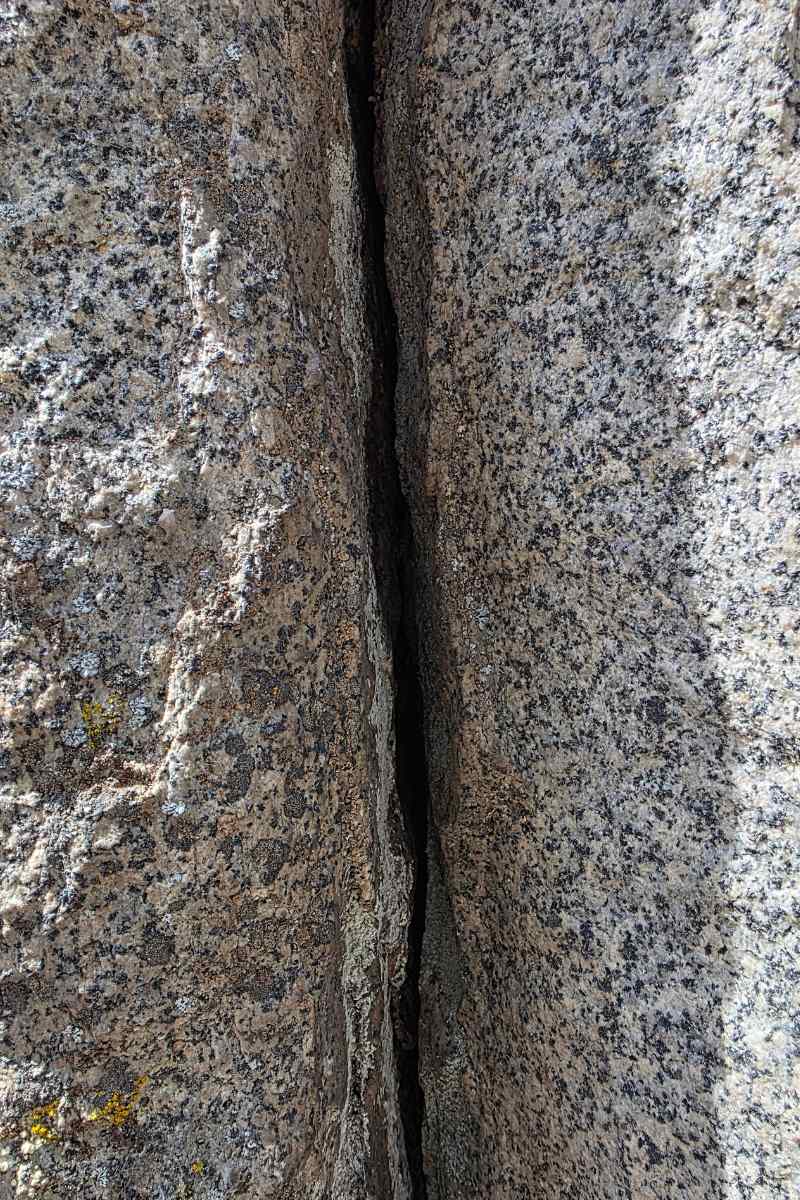

There is an interesting rock formation located a little ways outside of Whitehall, Montana, jutting out of the earth in a way that resembles nothing so much as a prehistoric wall—appearing to be made of cyclopean slabs piled on top of each other with startling exactitude. In places, you couldn't slip a credit card in between. It's been there for thousands of years, but it's only been internet famous for a handful.

But wait, maybe that's not the right place to start. Perhaps the true beginning of the story is thousands of years earlier, around the time of the Younger Dryas, a period of dramatic climate change that occurred over 10-12,000 years ago. The history books tell us there wasn't much going on back then, humanity-wise. Just a lot of hunter-gatherers poking around in the dirt, eating various roots and grubs while struggling mightily to invent language and culture. But the history books are wrong; this is the claim of popular author Graham Hancock. His legions of fans include Keanu Reeves, who sums up Hancock's unorthodox view thusly on season two of Netflix's Ancient Apocalypse program: "As a kid, I always thought the timeline was off." The timeline, that is, of human history.

Forget crawling around in the mud—prehistoric man was building massive megalithic structures using advanced methods now forgotten. Long ago, these now lost civilizations had knowledge far beyond the primitives we have believed they were. They had remarkable and profound understanding of masonry and the principles of architecture, science, and the decorative arts. But at some point around 10,000 years ago they were effectively wiped out by a mega-catastrophe big enough to boggle understanding—maybe an asteroid impact, or a gigantic flood like that described in the Bible (and a number of other mythological texts, including Gilgamesh). In his book Fingerprint of the Gods, Hancock articulates the beginnings of his controversial theory, and in subsequent books like Magicians of the Gods and America Before: The Key to Earth's Lost Civilization he has developed (and sometimes rewritten) the theory to account for an ever-widening array of potentially anomalous structures he or his disciples and converts have brought to the world's attention. Some, like the sometimes 90-degree angles of structures off the Bimini Islands of the Bahamas or what appear to be car ruts through the island of Malta, seem to argue that they were the products of man, and that Keanu, God bless him, is right and everything we know is wrong.

Or maybe the story begins on episode 2316 of the Joe Rogan Experience, one of the most popular podcasts in the world, which some talking heads credited with helping to elect Donald Trump for his second term. At minimum it is a show listened to and watched by millions of people the world over. On that particular episode, Mr. Rogan happened to be discussing those very Maltese cart tracks when he pivoted.

"I think it's called the Sage Wall in Montana," Rogan said to outdoorsman and guest Cameron Haines. "... These immense stones that look like they were placed there, who knows how long. And there's people arguing, oh, this is like natural." Rogan went on to repeat a rumor that the wall extended underground, like the Easter Island heads.

As Rogan's producer pulled up a photo of the wall online, Rogan pointed at it.

"Whoa. What the [expletive] is that, dude?"

His guest, apparently not too interested in the secret history of mankind, responded to Rogan's enthusiastic ideas with only slightly less verve: "Yeah, man, that's nuts." Eventually, Rogan moved on to discussion of the "ostrich feet people" of Africa.

Rogan's mention of the Sage Wall wasn't the first time the enigmatic structure was speculated to be man-made, but it gave the Sage Wall its biggest platform yet. Thousands of people rushed to their devices to Google it for themselves. Like seemingly everything now, they had to take their results with a grain or few of salt, as one of the images the search returns shows a tiny little human hiker dwarfed by an enormous, clearly constructed wall. No doubt, since the time of this writing, there are new AI-generated images of gargantuan walls out there to confuse and muddy the metaphorical waters.

Who am I to refute such august public intellectuals as Joe Rogan and Keanu Reeves? I had to see it for myself.

In truth, despite what may seem like a slight tone of sarcasm seeping into this article, I have to admit to being at least a little partial to Hancock's ideas. Like so many, I read his books, which are mind-bending regardless of their factual accuracy, at a young age (he's been publishing for more than thirty years now), when his books would occupy a spot on my shelf next to Erich Von Daniken and Zechariah Stitchen. Hancock's ideas, which seemed so intellectually swashbuckling, were certainly alluring.

They are also not entirely without merit, if you carry to their conclusion the ideas of astrophysicist Adam Frank and climate scientist Gavin Schmidt, the authors of a peer-reviewed scientific paper on what they called the Silurian hypothesis, named after the lizard-alien race from the UK's Doctor Who. If such a race, human or otherwise, of advanced technological and scientific knowledge has previously inhabited the earth, how would we even be able to tell? How much, in fact, of our own civilization would endure a century or two from now if we disappeared from the planet tomorrow?

Eventually, all that would survive would be the artifacts made of enduring materials: things made of bronze and stone. In the end, it could be that humanity in all its sophistication and advancement will be memorialized to our succeeding replacements as a producer of stone points and metal trinkets. If that. All of our stadiums, shopping malls, service stations and supermarkets would amount to no more than a thin layer of weird dirt after a few hundred years.

Hancock theorizes that ancient shamans, agents of that now-vanished superpowerful lost civilization, traveled the earth in the wake of that earth-shattering apocalypse (flood? Asteroid? Something else?). They benevolently sowed the seeds of knowledge in the form of megaliths they built or otherwise convinced the surviving local humans to build, from which can be derived the fundamental axioms of math and geometry. Over the years we have forgotten them, but signs of their existence are covered-up, ignored, and/or misunderstood.

So I visited the Sage Wall for myself, bringing a buddy named Matt Orson, as well as Ted Antonioli, geologist and member of the Tobacco Root Geological Society. We arrived to the Sage Wall at ten or so in the morning, and found its grounds beautiful. Chris Borton, founder of the Sage Mountain Center, musician, and onetime board member of the Butte Symphony, met us in the parking lot, in front of the beautiful house he has built by hand.

Borton explained the history of the property and of the wall he found, hidden by trees, back in 1996. In his own words from the Sage Mountain Center website, "People are traveling from all over the world and are expressing a variety of views of what they are seeing on this site, which include: a sacred structure of timeless spiritual healing, an ancient megalith built by early beings, or just another pile of rocks."

He almost seemed disappointed that so many of the visitors to his Sage Mountain Center, which focuses on sustainability and green living, are there to see the Sage Wall, but is eager to add that he will have the results of recent ground testing uploaded to his website soon, so that it can be ascertained how true are the rumors, parroted by Rogan, that the Sage Wall extends deep underground.

(Note: as of the time of this writing, no such report was ever uploaded to the website, and if he is in possession of epoch-changing results he has so far decided not to publish them.*)

((*Note on the note: Three days before the magazine hit newsstands, those materials were in fact uploaded, and the reader may appraise them for him or herself by clicking here.))

Borton reported that the Sage Wall has continued to take off lately, and that visitors were becoming more frequent. Indeed, while we were on our hike to the wall another interested party, a family with mom, dad and two kids arrived, cell phones in hand, to look at the enormous structure. My buddy talked to their dad about (what else?) the work of Graham Hancock, which had inspired the family to make the trip.

Meanwhile, I asked Ted what he thought. Choosing his words carefully, Ted reported that he thought the wall is remarkable, very cool to see, and probably natural—a single piece of the 75-78 million-year-old Boulder Batholith. The Batholith formed when magma got close to the earth's surface before cooling, resulting in jutting pieces of granite that, as they lost their heat, fractured, often in systematic ways that can, and frequently do, resemble geometric blocks. The Sage Wall, he says, is uncommonly straight but not anomalous enough to indicate, in his studied opinion, the work of a human hand. Or, for that matter, a reptilian claw.

We then asked the other fellow, the guy who had paid to bring his family on a lovely Saturday morning contemplating the secrets of lost civilizations, what he thought. He was politely ambivalent, noting that he could see the arguments both for and against construction as a provenance. In the end, I think he was happy to have had a nice hike on a beautiful morning, in environs that are beautiful whether they reveal ancient mysteries or not. He did not, however, manage to entirely restrain himself from grumbling about the price. I did a quick calculation in my head. If both of his kids were under seventeen, they got to take the hike for free. So that's $198 for them—$99 an adult. Kids, generously, are free. Our party, Matt, Ted, and myself, cost $297. Altogether, I figured nearly $500 wasn't a bad take for a Saturday morning.

If we were actually looking, I reflected optimistically, at evidence of a lost civilization that built, for some reason, a big wall amid a collection of broken pieces of batholith, in an area whose strategic importance must now elude us all these eons later? Well, then $99 a head is a pretty good price, all things considered. Of course, it only costs about 700 Egyptian pounds to see the pyramids of the Giza Plateau, which works out to be about $14 in our money.

Ted Antonioli, a lifetime Montanan, would surely agree that if Egypt is great, Montana is positively fantastic, probably enough to justify being a little over seven times more expensive than seeing the pyramids.

In his words: "It's worth seeing one way or the other, and it was a fun little hike."

Leave a Comment Here