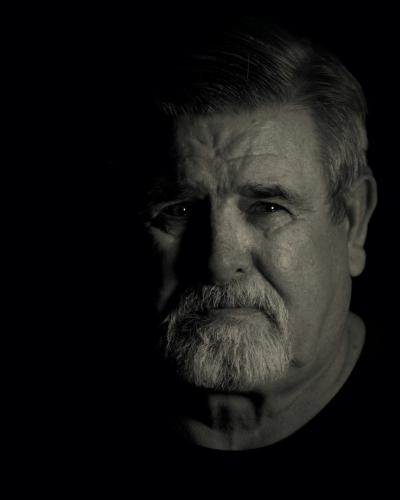

Interview with John N. Maclean, Author of "Home Waters" and Son of Norman Maclean

Hepworth

Home Waters refers to your favorite trout stream, the Blackfoot River in Montana. Yet you live over 2,000 miles away in Washington, DC. How can the Blackfoot River possibly be your home waters?

John Maclean

The family has scattered. My father and his brother Paul were born in Iowa. My dad spent his teenage years and early twenties in Montana, but he went away to college, to Dartmouth, and was off to Chicago in 1928, in his mid-twenties. And he returned, of course, in the summers. My mother was the only one of us who was born in Montana. She was born in Butte and grew up in Wolf Creek. She wanted to escape small-town life, but she, like all the rest of us, regularly came back. I grew up half in Montana, and it was certainly the place that I liked best.

What holds the family together? The Montana cabin at Seeley Lake has allowed us to keep coming back, to keep the connection.

Hepworth

You open your new book on the Blackfoot’s Muchmore hole made famous by your dad, and you also end the book there. Why?

Maclean

The Muchmore hole has been part of my life, early and late. My dad has an anecdote in A River Runs Through It about catching a big fish that almost surely happened on the Muchmore hole. I always wanted to go there when I was young, and I would say, “Gee, Dad. How come we don’t go do that?” And he’d say, “I knew a rancher there a long time ago, and we just can’t get in there now.”

Decades later a friend of mine from Chicago bought a ranch that borders the Muchmore, and I started fishing there. The particular fish that’s in the book is the biggest rainbow I've ever seen on the Blackfoot River. And I sat there afterwards and said to myself, “I’ve been thinking about this hole my entire life, and I’ve been trying for a fish like this my whole life.” And eventually that thought became a book.

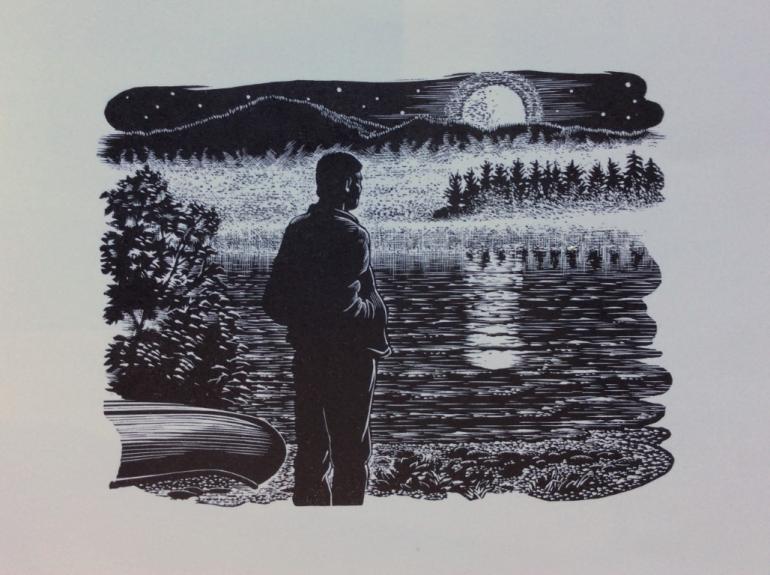

Engraving by Wesley Bates, courtesy of HarperCollins

Hepworth

Those original wood engravings by Wesley Bates in your book recall the illustrations in your father’s book. How much influence did you have over the physical design of your new book?

Maclean

A lot, for which I am thankful. I wanted to echo the illustrations of the first edition of A River Runs Through It, which has those wonderful wood engravings. It was you, Jim, who put me in touch with a guy who was doing an essay about the illustrations in A River Runs Through It. He and I then ran down the guy who had done them, Robert Williams, who had retired and was still living in the Hyde Park neighborhood in Chicago. Williams explained how he’d made the engravings, based on images my dad provided. I said to my editor, Peter Hubbard, “Why don’t we do something like that? Why don’t we have drawings at the head of each chapter?”

Once Hubbard found Bates, we passed draft sketches back and forth. The images at the beginning and end, for example, echo each other, and that took work. The one at the front shows three figures fishing in a big river, a tall figure with a little boy behind him holding a basket and a medium-sized figure downstream. They could be the Reverend Maclean, George Croonenberghs holding his basket, and my dad downstream, or even me holding George’s basket. The final image has one figure in a big river. That would be me on the Blackfoot. I’m the last man standing. The images have the same mood and tell the story of the book.

Hepworth

Are there connections between Home Waters and your father’s posthumous book, Young Men and Fire?

Maclean

I wouldn’t have written Home Waters if he hadn’t written Young Men and Fire. It’s as simple as that. I was at the Chicago Tribune in 1994, having done 30 years with the paper, when the South Canyon Fire in Colorado killed fourteen firefighters, similar to the Mann Gulch Fire in my dad’s book. A lot of people told me, “You should do a book on that,” and I thought, God almighty, why? We’d just been through all kinds of things getting Young Men and Fire into print, dealing with the effects of the movie of A River Runs Through It. It took almost a year before I quit the Tribune—I did not retire, I quit—and wrote Fire on the Mountain about South Canyon, and that got me started as an author.

Hepworth

Your five previous books more or less fall into the category of straight reportage. Home Waters is a memoir, a different bird entirely.

Maclean

I didn’t have trouble making the switch. I embraced it. Straight nonfiction narration is a wonderful genre—and I’ve been at it, I’m afraid, almost 60 years. But I found this new genre liberating and had a lot of fun doing it.

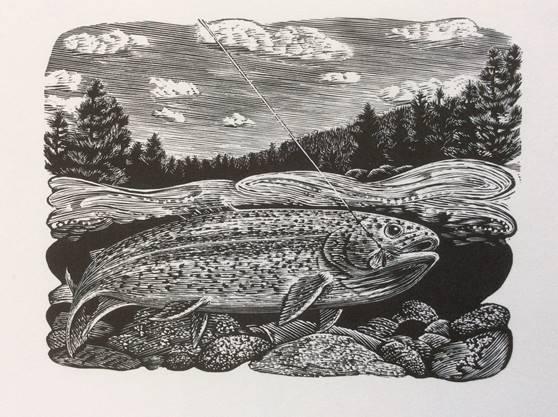

Fish engraving by Wesley Bates

Hepworth

Let’s talk a little bit about Montana as the place where you’ve been going for over three-quarters of a century. What changes have you seen, for better or worse?

Maclean

Our parents took my sister, Jean, and me to the Reverend Maclean’s church in Missoula to be baptized in 1944—the records are still there. Montana has changed a great deal since those days, but there are some constants. Seeley Lake, the town and the community, has always been based on timber, recreation and the Forest Service. There’s a ranger station there, a sawmill—Pyramid Lumber—that thankfully has survived the black hole implosion of the lumber business in the West. And, of course, there’s always been the summer crowd, the recreational crowd. But they’ve all changed in fundamental ways.

The Forest Service now is second-guessed to death. Big-time logging has vanished from public lands in the Swan and Clearwater Valleys. The recreation side has changed fundamentally because people with money have come in, sometimes year-round. The winter has turned into a recreational season with snowmobiles and cross-country skiing. So, you have a different culture coming in.

Hepworth

Your father referred to the Blackfoot River as “our family river.” Do you feel equally proprietary about it?

Maclean

It has changed for the better and the worse. When A River Runs Through It was published, the Blackfoot River was so impoverished as a fishery that state authorities didn’t even bother to do a fish count there. But the attention to the river especially from the movie of A River has resulted in so much use and overuse that it isn’t the river of my youth. It’s come back as a fishery, however, thanks to contributions mostly generated by the movie and an enormous amount of work by local groups and individuals.

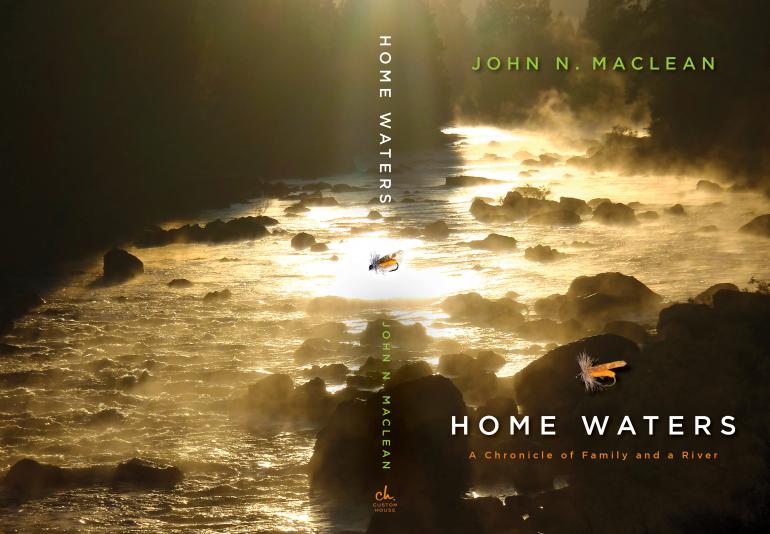

Source: HarperCollins Publisher

Hepworth

Let’s switch gears. Did you consciously start out to follow in your uncle Paul's footsteps by becoming a newspaper reporter?

Maclean

No. I did so unconsciously. Paul is a shadow person in my life. He has shaped my life without me being fully conscious of it. When I got into the news business, I discovered that it was exactly where I should be. I’m sure that was partly due to Paul’s example. But he was a negative example, too.

He had a wonderful job in Helena covering the state capital for the Helena Independent-Record. His unfortunate personal behavior resulted in him leaving the IR and moving to Chicago to take a job that his brother had arranged for him.

Hepworth

Why did you reveal so many details about Paul’s murder?

Maclean

There’s so much nonsense around about his murder that it’s almost a conspiracy cult. The facts are not pretty, but they are facts. I’ve collected documents about it for decades and talked to people who knew him. There were all these bizarre theories about his death, one being that Paul had been working undercover as an intelligence agent for the University of Chicago reporting on immorality and crime in the university neighborhood. He was an investigative reporter and it all caught up with him one night and he was murdered for his incisive investigation. That’s hogwash.

First of all, Paul wasn’t an investigative reporter, no more than any journalist. Anybody who reports news conducts investigations. Investigative journalism is a specialization. Secondly, he was a first-year employee in the U of C public relations department. He wasn’t somebody with deep knowledge of Chicago and the complex workings of vice and crime in the city.

It seemed to me that setting out honest-to-God facts about his death from witness reports, official proceedings, statements made at the time, remembrances by those who knew him, the final conclusion of the police—was an important exercise.

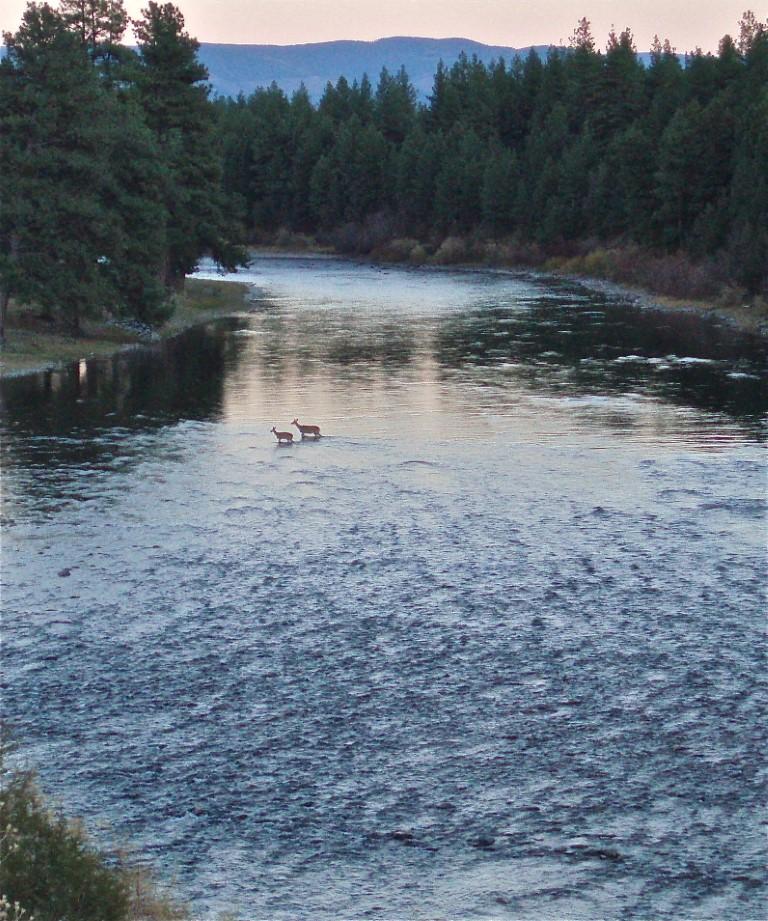

Photo Credit: John N. Maclean

Jim Hepworth and John Maclean have been fishing together off and on for at least two decades. As the director of Confluence Press, Hepworth conceived and published the first book about John’s father, Norman Maclean. Hepworth has a book of interviews titled Stealing Glances: Three Interviews with Wallace Stegner.

Leave a Comment Here