The Persistence of the Little Shell People

It’s remarkable that the Little Shell Chippewa persist. Theirs is an epic story that dates back to the last unresolved circumstance from the Northern Plains Indian Wars of the 19th century. This small cohesive group of marginalized people has never surrendered. We are now into the seventh generation of struggle since buffalo culture collapsed. What other sector in contemporary society has such a story? No one alive in Montana today has ever known a time when the Little Shell were not fighting Washington for restoring their rights.

Even though the Chief Little Shell II (Broken Arm) signed the 1855 Blackfeet Treaty, the government never came back to treat for Little Shell nor any lands north of the Missouri in Montana. Those lands were commandeered by the U.S. Army during the years 1868-83. Then, in 1892, the government exiled the Pembinas Chippewa Cree Michif (who are the Little Shell Tribe), stripped them of their hereditary lands, and banished from citizenship. The Little Shell have learned to survive outside the Reservation System in their unique niche of Montana and American society.

So, how did this situation come to be. Early on (1650s), the Chippewa Cree Michif began incorporating Euro-heritage into their Indigenous sphere. They were considered by Anglos to be Metis (French) or Halfbreeds (English), two words meaning the same thing: not 100% pure anything. The Metis are a full-flowered modern Indigenous society. Some Little Shell are Metis. Some self-identify more toward their traditional historic Indigenous background. There are a range of identities within being Little Shell, just as the wider America.

Since 1887, the U.S. uses the racial construct of blood quantum to divide Indian America, historically eliminating half their treaty responsibility in a pen stroke, and the rest disappearing over time, dividing by each new generation. Sorry, Uncle Sam, it’s not about race. It’s not what was here when Anglos showed up, it’s about who was here.

What a story—5,500 Chippewa Cree Michif directly related to all the tribes on both sides of the Medicine Line, plus Cheyenne, Crow, Salish, and Kootenai—we have to ask, “unresolved for over 125 years?!” We’re trying to work our way out of the colonial past.

The Chippewa Cree Michif have been in Montana since the 1730s as buffalo hunters with their Assiniboine relatives and as allies of the Blackfeet in their Shoshone war. When the buffalo disappeared (1883), the government shut down all claims. A high wind of institutional and bureaucratic violence blew far afield most Little Shell from those lands. There remain descendants in Sheridan County and region. Trenton Service Area was set up in the 1970s to manage surviving Turtle Mountain allotments. The Fort Peck Assiniboine have a significant historic Chippewa Cree Michif population among its bands. The Chippewa Cree Michif communities along the Milk River remain inhabited since they were wintering sites of old. A good portion of Little Shell in Billings, on Cheyenne, and Crow have northeast Montana and Turtle Mountain connections.

The land-sharking in northeast Montana left many disfranchised and landless. This was just the warm-up for Louis Hill (son of J.J.) and his Hi-Line land developers, businessmen, and politicians seeing a wealth of land leaving the public domain and going to those dang half-breed Indians.

Then the feds announced the homeless Indians of Montana were going to “be given” all those lands east of Fort Peck to the North Dakota line. Known officially as “Rocky Boy Indian Land,” it existed for a year as a reservation. In 1908, the General Land Office withdrew 1.4 million acres of prime public domain in the Medicine Lake/Sand Hills area. That would consolidate the Montana homeless Chippewa Cree Michif non-treaty buffalo culture collapse Displaced Peoples (DPs).

This is the whole Medicine Lake ecosphere we’re talking about. Big time beauty. By late 1909, the Department of the Interior announced the “Opening of Rocky Boy Lands,” basically returning that 1.4 million acre set aside to the public domain, complete with instructions for white folks to get it while it’s hot.

After WWI, the Little Shell reorganized as the Abandoned Chippewa of Northern Montana. Those days, the Indian Office thought they took care of the Landless Indian Problem in creating a reservation in 1916-17 for “Rocky Boy’s Band of Chippewas and such other homeless Indians of the State of Montana.” We’ve come little further with the BIA. Congress is the hope.

All along it’s been a federal responsibility. The Indian Office first acknowledged it, saying it could do nothing without Congressional appropriations. Since WWII, Congress and the BIA just deny it. State and local communities have been doing the heavy lifting all these years, helping. The Little Shell have made a niche for themselves. These neighbors of ours, their people ran buffalo in the wild. They lived the transformation from an Aboriginal to an Anglo world. Anglos took their land, they asked for pennies; we gave them neglect, they give us hope. Truly, it would not be Montana without them. That said, they still need what they are owed, federal acknowledgment. We owe them—and ourselves—that much.

Nipakwašimowin Lodge, Dunseith, ND. Traditional spirituality remains strong among many Little Shell.

Émilie Pigeon and Estella Ruth Delorme Garcia. Dr. Pigeon doing research for the Little Shell discusses family history with Estella.

Representatives from Louis Riel-Gabriel Dumont Institutes visit St. Peter's Mission, Bird Tail, MT. In 2014, a delegation from the two scholarly arms of the Metis Nations of Manitoba and Saskatchewan came to Montana to work with the Little Shell on language retention. Seen here, l. to r., are David Morin, Norman Fleury, Karon Shmon, Lawrie Barkwell, and Little Shell Council-member Kim McKeehan.

A two-room school, Bynum School Class visits Metis Exhibit, Central MT Museum, Lewistown, MT.

Little Shell Tribe member Jim Martinez donates central Montana point collection to the Tribe. A nationally significant museum’s worth of Pembina cultural materials are among the families of Little Shell members. As the tribe’s ability to care of more increases, more will come forward.

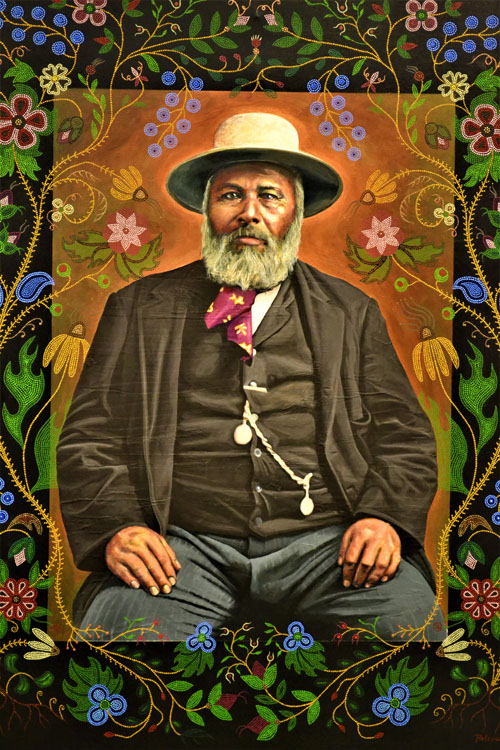

Christi Belcourt, “Can I Get Picture With You Gabe?” acrylic on canvas, 36" x 48", Gabriel Dumont Institute Museum Collection, Saskatoon, SK. Renown Metis/Michif artist, Christi Belcourt shows us Ol’ Gabe Dumont in Gibraltar pose. Gabriel was related to the Berger’s through his wife Madeleine Wilkie, whose sister Judith was married to Pierre Berger, grandson of the LaVerendrye expedition. As a youth Gabriel ran buffalo up and down the Plateau du Prairie du Coteau that defines the region.

St. Ann's Day Procession. St. Ann, mother of Mary, is the patron saint of the Metis.

by KRTV NEWS

Published on Sep 12, 2018

VIDEO DESCRIPTION: The U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill on Wednesday that will provide federal recognition to the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians.

Leave a Comment Here