Quintessential Cowboys: Celebrating the Diversity of Montana's Cowboy Culture

For some, the image of the cowboy looks more like John Wayne or Roy Rogers, but the reality is far deeper and richer than the glamorized perception of the Old West.

"That's Hollywood," says Christy Stensland, executive director for the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame & Western Heritage Center. "For Montana, cowboys have always been diverse."

Stensland points out that those who worked cattle came from all walks of life. Outward appearances and social norms were less important than competency. In this regard, these four inspiring characters, who are all inductees in the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame, exemplify the toughness and tenacity of Montana's Western heritage.

These are but brief glimpses into the rich lives of these quintessential cowhands who exhibited the grit and tenacity that made them stand out in an already impressive crowd. For more detailed accounts of their lives, visit the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame & Western Heritage website at montanacowboyfame.org!

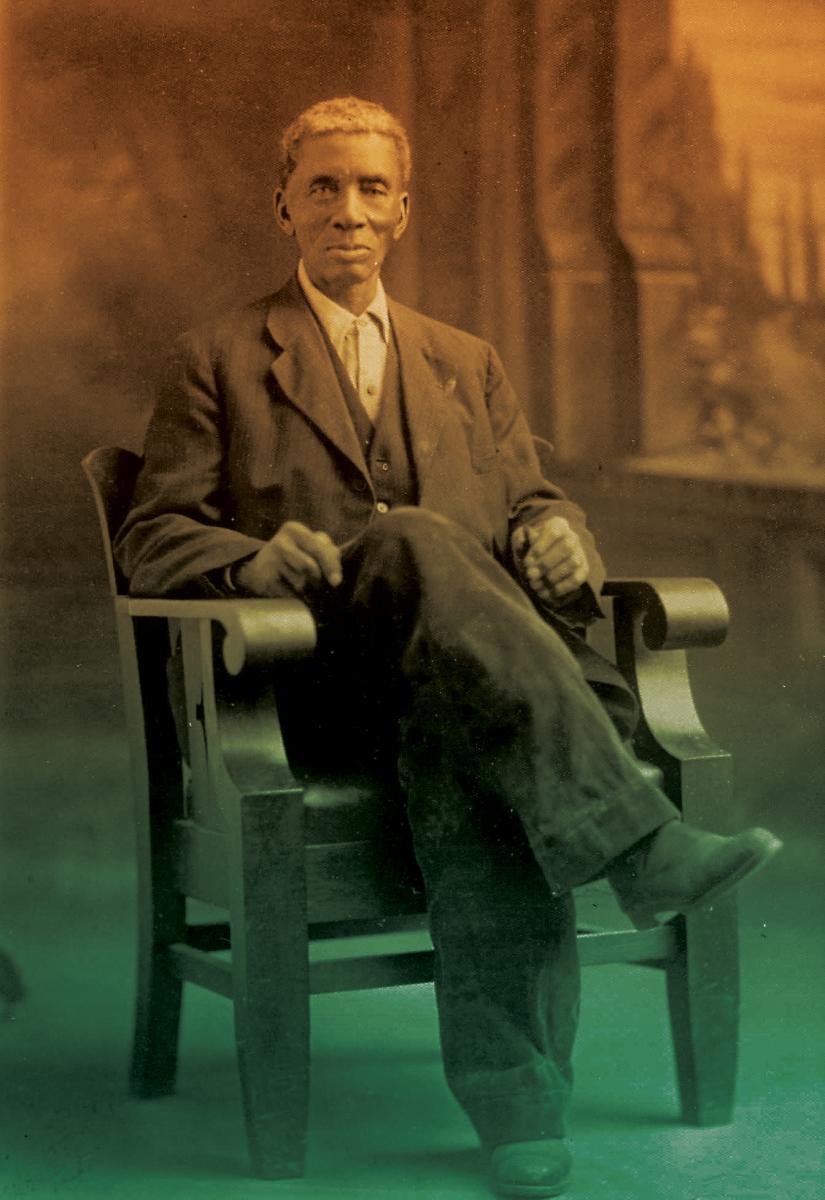

Joseph "Proc" Proctor

The year of Joseph 'Proc' Proctor's birth is unknown, but he spent his early years in slavery on a Texas cotton plantation. Although he was very young, he would later remember his father being sold to another farm, and noted that he also remembered the day of their emancipation, when every freed person received a sack of corn.

Proc gravitated to the world of herding cattle and wrangling horses, eventually working for an outfit that bought a ranch on the Crow Reservation. By 1879, three short years after beginning his cattle career, he was already well-known as one of the best ranch hands in the region.

In 1901, he married Elizabeth "Lizzie" McHarg, a young Black woman from Missouri who worked at the ranch. The couple settled in the small community of Castle Rock, located near Colstrip. There they raised their daughters, Sarah and Martha, who were equally proficient with horses and cattle.

Being a Black man in this post-Civil War world was not always easy. According to research from the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame, it was typical of Proc not to eat with the other men. He took his food and sat off by himself. He would always accept company but never initiated it, possibly a habit learned in youth.

A more volatile incident occurred after his group finished shipping the cattle and headed for a drink at a nearby saloon, inviting a cowboy from Texas to join them. The courteous invitation turned into a tussle when the Texan rudely refused to drink with Proc.

The respect Proc earned in the eyes of those who knew him was summed up in his 1938 obituary: "Though of a different race, the tolerant, generous minded folks of the West accorded the late Mr. Proctor every consideration and courtesy and kindly disposition and gentlemanly traits of character served to implant in the minds of who knew him that their confidence in, and esteem for, him were never misplaced."

Belknap "Ballie" Buck

Growing up as a Metis, someone with Indigenous and European parentage, with an Assiniboine mother and white father, Belknap "Ballie" Buck straddled both worlds with style. Born in 1872, his mother, Spotted Hail Stone, named him Wolf-on-a-Hill, but he was raised primarily by his father, Army Captain Daniel Buck, and his stepmother, Susan. At eight, his father sent him to a horse operation where his innate talent was obvious from this young age.

As Ballie matured, his father wisely told him, "You're going to be big and strong, but unless you're a gentleman, you'll just be big." Ballie took it to heart, and was renowned by those who worked with or around him.

A born storyteller, Ballie and artist Charlie Russell naturally became close friends, with the two sharing their love and memories of their days on the open range before the West was fully civilized. Both of them mentioned each other in tales, such as in Ballie's account, "When Lowry Took Russell and Me to Eat," as well as Russell's stories about Ballie in "Rawhide Rawlins" and the "Night Herd." Ballie also shared Russell's penchant for sketching his first-hand reminiscences of cowboy life, his art winning awards at the Montana State Fair.

The brutal winter of 1906-1907 was a turning point in the cattle industry. After the devastating losses, numerous cattle outfits decided to coordinate one last open-range roundup. Among all the wagon masters required to move over 130,000 cows, Ballie was unanimously named captain, evidence of the high esteem of his counterparts. This respect extended beyond the border, as Ballie was also asked to be the bucking horse judge in the first Calgary Stampede in 1912.

While Ballie seemed to successfully navigate the differences in his heritage on a professional level, his personal life brought unique challenges. When Ballie met Myrtle Dennis from Canada, whom he called his "Queen from Ontario," the couple became serious, much to the dismay of her family. Although her family ultimately disowned her, they were married for 34 years. They lost their only son, Stephen Webster Buck, when he was only two. After retiring from the cattle industry in 1930, Ballie was appointed Deputy Law Officer in Augusta four years later.

He was respected for good reason. Teddy Blue Abbot, an early cowhand, summed up Ballie's career best in his memoir: "Way up Sun River, close to the Shining Mountains, where the grass grows plenty and the water is sure cold and clear, lives 'Judge' Ballie Buck, now running a cow outfit, who for many years was one of the best-known cowpunchers in northern Montana."

Marie "Ma" Gibson

With a father who owned a livery stable, Marie Gibson worked with horses all of her life but was still an unlikely bronc and trick rider for her time.

Launching into adulthood as a bride at 16, and a mother shortly afterwards, Marie's first few years were filled with marital and parental obligations. Yet, after the couple's marriage fell apart, she found her calling working with horses once again, winning third place in horse racing at the Great Northern Montana Stampede in 1917, her professional debut. She earned the World Champion Cowgirl Bronc Rider title at Madison Square Garden a decade later.

She amazed audiences on the rodeo circuit traveling throughout the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. While performing at the Tex Austin's International Invitational Rodeo in London, the Prince of Wales, eventually crowned King Edward VIII, gifted her with a prize horse as a token of his admiration of her riding skills.

Marie described some of her tricks, as documented in the book Cowgirl Up: A History of Rodeo Women by Heidi Thomas, "Standing up on the saddle, going under (the horse's) belly at full speed, going under its neck, laying across his neck with hands and feet free… The Russian drag, hanging with one foot, your head and hair dragging at full speed." Her life was riddled with severe injuries.

Her last ride was a successful run on a bronc. When the pickup man rode in, her bronc was still going at it full speed. The two collided, sending her horse to the ground. The impact fractured her skull, and she died within hours at the much-too-young age of 38.

Libby "Cattle Queen of Montana" Collins

Libby Collins was born in 1844 in Illinois. The Collins family were true pioneers, eventually landing in Colorado before a devastating flood prompted 17-year-old Libby and her brother to work for a cattle outfit that traveled from Denver north to the Missouri River. Working as a cook for a 100-wagon train between Denver and the Missouri River, she made a dozen trips across the plains, experiencing every hardship this wild land could muster.

Arriving in Virginia City in 1863, she moved between mining towns. At Canyon Creek, she met Nathanial Collins, a former vigilante and silver miner. They married in 1864 and built their own cattle operation. Moving to the Teton River near Old Agency in 1877, she befriended the local Blackfeet, and with her training in nursing, tended to many of the sick in this remote area.

As their cattle operation grew, they moved near the Bellview area outside of Choteau, and unlike other producers, directly shipped their cattle to the Chicago market. Unfortunately, by the second year, her husband could not physically accompany the shipment. Libby stepped up to the task.

From a newspaper report noted in her write-up as the 2012 inductee in the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame, "Mrs. Nat Collins has earned for herself the distinction of being the first and only lady in Montana to raise, ship, and accompany the train bearing her stock to the Chicago market and personally superintend the unloading of the animals and their sale, and throughout the length and breadth of the land she is known as 'The Cattle Queen of Montana.'"

- Reply

Permalink