Granite, Silver, and the Dollar: The Making of a Ghost Town

Granite was founded in the 1870s, situated over a few particularly rich veins of silver ore. It was a big enough town to have neighborhoods roughly divided by country of origin, with a Finnish street, a Cornish street and, of course, an Irish street. It contained a hospital, a bathhouse, a famously excellent dance floor at the Miner’s Union Hall, several fraternal orders, eighteen saloons, many of which contained brothels, and, finally, four churches.

In an ostentatious display of the area’s mineral wealth, the Bimetallic company, then the owners of most of the area’s silver mines, sent a gargantuan bar of silver weighing over two tons to the 1893 world’s fair.

But by the late summer of that same year, Granite would be abandoned, a newly minted ghost town. It would bubble back to life fitfully over the next quarter century before being abandoned completely in the first half of the twentieth century.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that a great many of the ghost towns of the West are the result of closed mines—no other resource was as volatile, as subject to the unpredictable highs and lows of the economy. The demand for gold had established small, rough towns like Virginia City, Nevada City, and other Alder Gulch camps. But then Montana’s gold boom had been supplanted by a tenuous silver boom. Some of the gold camps emptied. Others disappeared entirely, as silver mines popped in the Philipsburg area and in Helena. On the horizon was the widespread adoption of electricity, creating a demand for copper that would turn a dirty, unremarkable little gold camp called Butte into a legend. But for every Butte there were ten Granites, or Rumseys, Kirkvilles, Hendersons, Black Pines, Princetons, or Southern Crosses.

Photo by Bryan Spellman

During the Civil War, the Union had issued “greenbacks,” America’s first federally issued “fiat currency,” or paper money not tied in value to gold or silver. It was a desperate, if necessary, measure, as the Union did not have enough gold bullion to fund its own war effort. The Confederacy did the same, and their respective currencies rose and fell in value as their fortunes did.

Previous to the war, money was always backed by gold and silver, mostly at a fixed rate of exchange established by Alexander Hamilton. Though some adjustments to the exchange were made over time, it was largely agreed that 15-16 ounces of silver would be worth once ounce of gold.

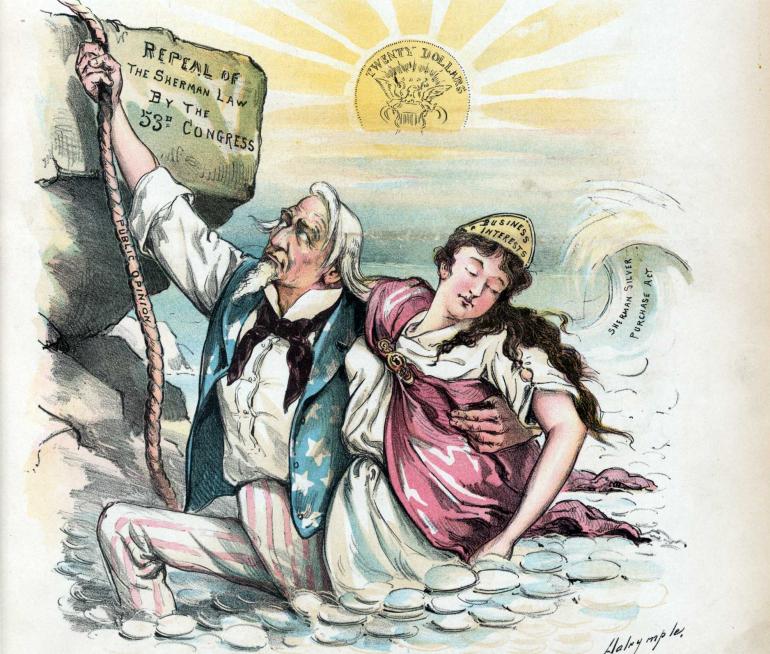

Following the Civil War, however, the newly reunited states had to decide what form their currency would take. Moreover, most of the country was undergoing deflationary prices, meaning that the American farmers were working harder to pay debts while making less and less money on their produce. This was compounded by the Coinage Act of 1873, known for decades as the “Crime of ’73,” which eliminated silver and established the gold standard. Soon depositors took their silver notes and went to exchange them for the metal, something which had been promised by the federal government since the time of Alexander Hamilton, only to find that they could no longer do so.

For the next quarter-century or more, the question of gold and silver would change the face of Montana, and the country.

For the next quarter-century or more, the question of gold and silver would change the face of Montana, and the country.

The reestablishment of silver as a form of currency became a popular cause, particularly among indebted farmers and, not surprisingly, Western silver mining interests. The farmers reasoned that if the prices of their produce went up, they could more easily pay their debts, while a precipitous fall in the value of silver meant that it was no longer profitable to mine for the ore at all.

In 1890, a prescriptive piece of legislation was passed that would stop short of coining silver but would require the government to buy 4.5 million ounces of silver a month. The demand for silver was back.

There were, however, a few problems. For one, the law required that the government pay for the silver with treasury notes that could be exchanged for either silver or gold. The problem was that the monetary value of silver was much higher than the actual value of the metal on the open market. As a result, shrewd but unsavory interests could make a lot of money buying silver by exchanging it for gold with the treasury at the artificially established rate of 16 to 1, and then sell the gold on the metal exchange, where its value in weight would far exceed the value of the original investment in silver. If this were performed over and over, which it was, it would eventually cause the banks to run out of gold, destabilizing the country’s economy.

The result, in part, was the Panic of 1893, during which some 15,000 American businesses and 500 banks failed, stock prices fell, and 25 percent of the American railroad business went into receivership. President Grover Cleveland, faced with rapidly dwindling gold reserves, repealed the Silver Purchase Act of 1893.

News travels fast, even in the year 1893: silver had lost nearly all its value. For the residents of Granite, there was no reason to be mining silver, no reason to continue working in the ground, no reason to return to their homes—in fact, there was no longer, as of a minute ago, any reason to live in the town of Granite. The government was no longer buying silver, which meant that there was no longer any real market for the precious metal. The Granite Mountain Mining mill engineer tied open the whistle at the silver mine, allowing its shrill call to spread the message: go home, pack up, and leave. Granite was no longer a town.

The effects of the Panic would be felt for decades. But after 1900, when the economic situation began to look better for America, the country settled on a gold standard with comparatively scant debate. In the decades following WWII, however, the government would return to its Civil War-era notion of fiat currency, paper money backed by the government’s assurance and the market’s consensus that it has value.

For Western silver mining interests, the repeal of the 1893 Silver Purchase Act was the kind of economic calamity that produced so many ghost towns over the state; an unexpected change in the financial winds, and all of a sudden what was once a growing concern becomes a wind-battered ruin flirting with collapse, literal and metaphorical. The next round of Montana ghost towns would be created thirty or so years later, not by mining, but by the boom and subsequent bust of dryland homesteading in eastern Montana.

Photo by Bryan Spellman

Today, there’s not much of Granite left to see. A bank vault, stubbornly still standing despite there no longer being a bank to house it, the skeleton of the old Miner’s Union Hall, the Granite Mine superintendent’s house, and a handful of shacks. The site is a state park, and can be reached via a narrow, winding road up into the hills. Many go to take photos, and to try to imagine a vanished Montana, but no one lives there. No music is played there. No one drinks at any of the eighteen saloons, of whose former existence almost no physical evidence now exists. Finnish, Cornish and Irish Streets are grown over.

On the one hand, the ruins of Granite are a sobering reminder that we can’t predict what will happen to our communities any more than we can predict the market with certainty. We can’t know, twenty, fifty, or a hundred years from now, what will be the newly abandoned ghost towns of Montana.

On the other hand, maybe the little ghost town is a symbol of survival. Granite may be a ghost, but we’re still here. And so is Montana.

Photo by Bryan Spellman

- Reply

Permalink