Montana in 30 Years: YELLOWSTONE

Interview with Ann Rodmanmm Supervisory GIS Specialist, Yellowstone National Park

From a scientific standpoint, what do you believe will be the significant changes in Yellowstone by the year 2049?

The following climate trends are already happening and well documented using climate data from the last 30-70 years. I believe that these trends will continue into the future and that the rate of change is likely to increase.

Hotter and drier: The minimum temperatures (coldest temperatures in a 24-hour period, usually the temperatures at night) are warming faster than the maximum or daytime temperatures. We aren’t getting the multi-day stretches of extremely cold temperatures that used to occur during cold winters. By mid-century it will be much warmer at all elevations across the park, with temperatures estimated to increase at a rate of 4.8 oF/century. At mid-elevations, we’ve lost many of the nights that used to go below freezing during the summer. By 2049 we estimate that the park will lose about half of the days that still go below freezing in a year.

Lower snowpack (less total snow), shorter winters: We’ve looked at long-term (> 35 years) records of snow accumulation, and the snowpack levels are trending lower in Yellowstone and throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. We will still get winters with lots of snow, but the long-term trend is clearly for less snow in the future. One analysis found that by mid-century, snow levels across the Northern Range will decrease by 68% to 90%. We won’t be using snowmobiles to get to Old Faithful in the winter of 2049. By April, 2049 the mid and lower elevation areas of the park will be mostly snow free.

Earlier runoff, lower flows, warmer water: Warmer temperatures in the spring already trigger earlier melting of the snowpack and earlier peak flows in the rivers. Low snowpack years result in low flows in the rivers during the summer and fall. When the low flows correspond with high summer air temperatures, the water temperature is elevated above normal and there are negative impacts to the native fish that require cold water to survive. A recent study predicted that mean August stream temperatures in Yellowstone’s Northern Range will increase by 1.5 oF by mid-century. Conversely, during high snow years, warmer temperatures in the spring cause a lot of the snow to melt quickly, leading to downstream flooding events.

Longer growing season: The growing season in the park is getting longer. Winter is shorter, spring happens earlier, and the nighttime temperatures don’t get as cold as they used to. After analyzing data from across the park’s Northern Range, we concluded that the growing season is approximately 30 days longer than it was 50 years ago. Thirty years from now it might be a month longer than it is now. This means that the onset of spring green-up, which drives ungulate migrations, the timing of insect emergence, and the weather conditions when migratory birds arrive are all changing.

More frequent, large wildfires: A longer growing season means a longer fire season. Warmer summer temperatures drive more evapotranspiration (loss of water from plants and soil) leading to drier conditions. As unusually hot and dry conditions become more common, the potential for large wildfires increases. If we start to get 1988-like conditions every 5 to 10 years (as some scientists are predicting) instead of every 150 years, it will clearly increase the chances that big fires will occur more frequently than they do now.

What are you seeing today that shapes your view on the future of The Park and its ecosystem?

Here is one example that is happening now and will only get worse. Invasive non-native plants have always been good at taking over areas of disturbed soil, like the compacted zones along road sides. Conditions driven by climate change (early moist spring and hot, dry summers) are helping these non-natives become more successful at moving into undisturbed native plant communities, especially at the lower elevations in the park. In some locations near the North Entrance and Gardiner, native communities have been completely replaced by non-native, invasive annual plants. These invasive plants take advantage of early season soil moisture, depleting it before the native plants start to grow. This competition for soil moisture, combined with hotter and drier summers, is changing the composition of vegetation communities. The Northern Range is critical habitat for the park’s large mammals. To protect this habitat, and the ecological processes it supports, we are implementing actions to reduce the spread of these non-native, early season invaders and keep them from gaining a foothold in higher elevation habitats. This is difficult, time intensive work, but well worth the effort if we succeed.

What surprises you about changes you are seeing in The Park?

I am surprised by how fast some of these changes are happening. There is a location northwest of the park, between here and Bozeman, that has lost more than 90 days below freezing per year within the last 30 years. That is an extreme example, but that same trend is happening in the park at the Northeast Entrance, Sylvan Pass, and just about everywhere we have adequate weather records. The rate of change is likely to increase between now and 2049.

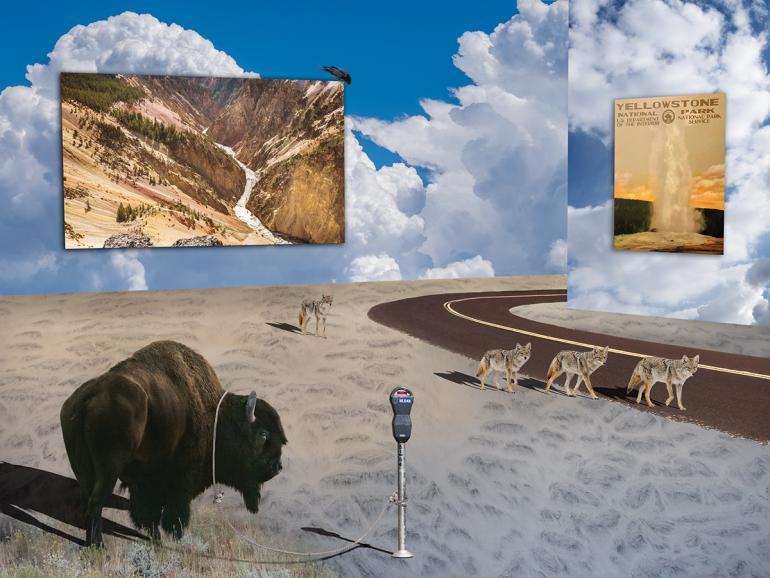

© NPS photo by Neal Herbert; October 2014

Can you take us for a short tour through Yellowstone as if you were in the year 2049 and tell us what you see?

You’ll need to use the mass transit system or plan ahead for a reservation if you want to drive your private vehicle through the park. These restrictions resulted from a rapid increase in summer visitation, driven by people wanting to escape the extreme hot weather in other parts of the country. If you haven’t visited the park since 2019, the lack of forests will probably surprise you. Many years of warming temperatures and drought, combined with the frequent occurrence of stand-replacing wildfires, has changed hundreds of thousands of acres that used to be covered by whitebark pine, Englemann spruce, subalpine fir, and lodgepole pine into wide open meadows and shrubland with scattered young trees. The bison and elk seem to be doing well, but you aren’t hearing or seeing many of the bird species that used to be common in the forests. It’s too bad that the historic structures at Tower/Roosevelt and Canyon Village were also lost in the fires. The new lodge and restaurants are nice, but they don’t have the same ambiance and historic authenticity as the original structures. You won’t be able to fish for native trout during this mid-summer trip, because fishing season is now limited to the early spring or late fall. At least the park still has native trout, unlike many of the lower elevation streams in the region.

How will the park’s wildlife adjust to changing climate conditions, and what species may be the most affected?

It is much easier to make predictions about climate variables than it is to guess how the complex interactions between animals and plants will play out as they respond to the new conditions. A lot depends on how rapidly conditions change between now and 2049.

Some animals are more directly affected by warmer temperatures, Yellowstone cutthroat trout and pikas for example. Native fish, like cutthroat trout, have evolved to live in cold water and can’t survive in waters above a certain temperature. As park waters warm, the cold water habitat these fish depend on will shrink. They will have to find pockets of cold water or migrate to places(higher elevations) with cooler water. Pika do best in the cooler temperatures common at higher elevations. As average summer temperatures across the park continue to increase, the suitable habitat available to pikas will contract. Over the winter, snow acts as an insulator for the pikas, shielding them from extremely cold temperatures. As the snowpack gets thinner, though, pikas and other animals, including overwintering insects, will lose that protection, adversely affecting their survival rates from one year to the next.

Some animals are indirectly affected because the changing climate is driving changes in the availability of the food they depend on. In the spring, ungulates follow patterns of green-up and snow melt across the landscape. The predators follow their prey. As the timing and locations of these patterns change, the entire ecosystem is changing, reacting, and rearranging itself in response to the new conditions. This change in timing is wide-reaching, affecting more than just the large mammals most visitors are familiar with. For example, migrating birds depend on certain foods and favorable weather conditions when they arrive in the spring. The successful pollination of flowering plants largely depends on the timing of insect emergence overlapping with when plants bloom. The success of these events up till now has based on the historic climate, not on a future climate that will be different.

Is there anything that can be done at this point at a macro level to mitigate undesirable outcomes as you describe them?

The rate and magnitude of future changes to the climate are still to be determined. That’s good news, because the magnitude of undesirable outcomes by 2049 still depends on the choices we make between now and then. It will be a mistake to downplay the importance of choosing wisely. Some drivers of current and future climate change are already locked in, so we need to anticipate the likely range of future Yellowstones and adjust our strategies to mitigate unacceptable outcomes. The new normal is rapid and continual change. Yellowstone, and other land management agencies in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, are re-assessing our conservation goals and strategies, taking likely future climate scenarios into consideration to improve our chances for success. For example, Yellowstone resource managers are currently introducing native cutthroat trout into high elevation streams because those locations are more likely than lower elevation streams to retain the cold water habitat needed by the fish now and in the future.

What can the towns at the entry points of Cooke City, Gardiner and West Yellowstone do to help park ecology and create positive human impact?

Gateway communities have a huge potential to educate and inform the millions of visitors that pass through their stores and hotels each year. Help people understand that their actions have impacts. Leading by example is very effective. Highlight local efforts that celebrate water and energy conservation, along with recycling and reusing materials to reduce waste. This raises awareness that individual actions have consequences and supports the park’s efforts to be a good steward of the natural and cultural resources protected within the park.

Is there anything that the millions of people who visit The Park can do to help alter the more harmful aspects of scientific projections?

Be aware of your impact and try to reduce unnecessary wear and tear on park resources. For example, when visitors park outside of designated parking areas or use unofficial social trails, they damage native vegetation, compact the soil, and increase the chance that invasive, non-native plants will become established. When park rangers restrict fishing because of hot temperatures, respect these closures and help educate your fellow anglers about how these restrictions help to protect our native fisheries. When possible, share rides. Fewer vehicles entering the park reduces harmful emissions, parking lot congestion, and waiting lines at entrance stations.

Ann Rodman oversees the Climate Program in the Yellowstone Center for Resources. After earning a Bachelor’s degree in Geology and a Master’s in Soil Science, Ann got started in Yellowstone mapping soils and fires during the summer of 1988. In addition to working on climate change, she also supervises the GIS (Geographic Information Systems) Program and monitors impacts to air quality and natural soundscapes.

Leave a Comment Here