Rozette Revealed: The Journey of Robert Sims Reid, Montana Author, Montana Officer

Robert Sims Reid—Bob—has lived in Missoula since 1975. He grew up in Winchester, Illinois, on what he describes as "the kind of farm that doesn't exist anymore". Winchester's population has been around 1,600 for 120 years. He notes its lack of a grocery store.

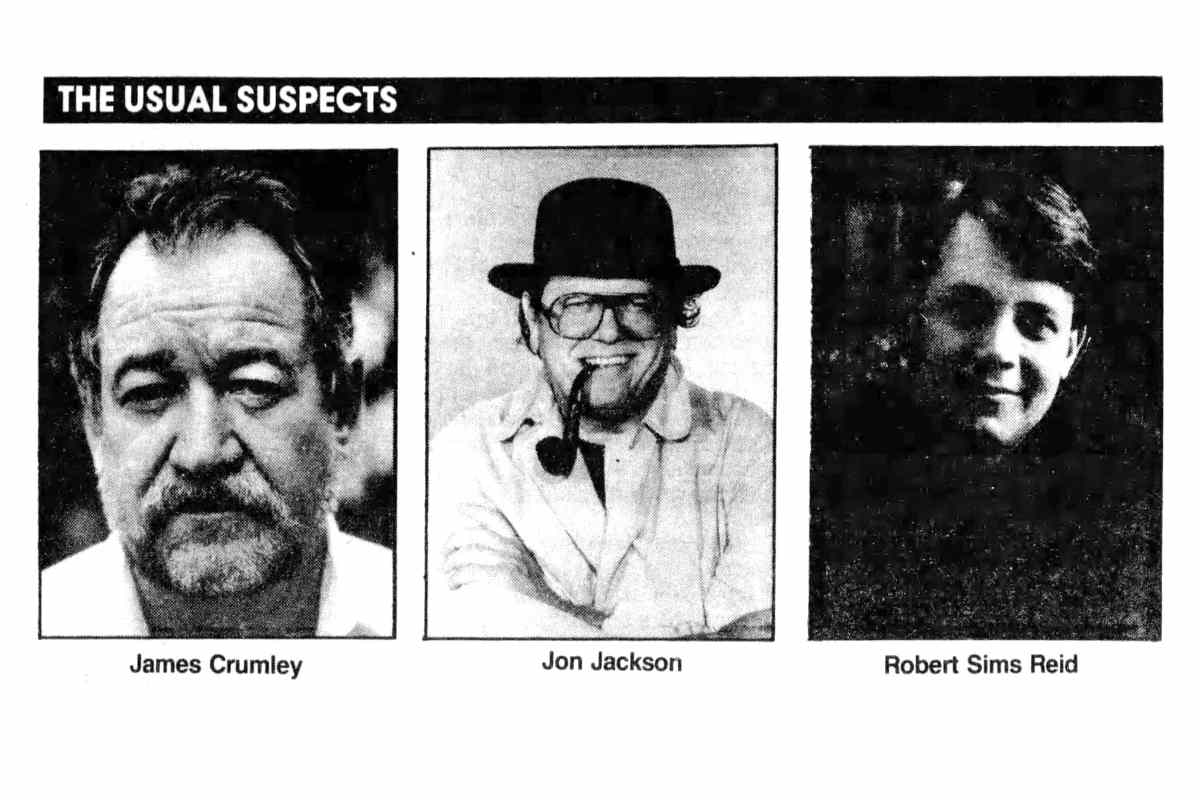

You might wonder, who is Bob Reid? You may have missed Montana's zenith of homegrown crime novels in the 1980s and '90s: Crumley, Jackson, Reid. He wrote authentic Montana cop tales because he was one. Titles like Big Sky Blues and The Red Corvette received national acclaim and intrigued French readers. By the millennium, though, the novels stopped coming out.

"Well," says Reid, "the books didn't make anybody any money". He sits with a cup of black coffee and a fine view of the mountains in the shade of his back porch. Birds sing. A Buddha statue faces from a tranquil backyard. The books may have stopped, for now, but he still writes. He writes for what the craft means to him, not the market. After years of balancing full-time police work with a literary career, sleeping four or five hours a night, he now writes at his own pace.

Reid first experienced Montana in 1969. The Air Force brought him to the radar station at Lakeside in the Flathead Valley. He remembers bus rides to radar towers atop Blacktail Mountain. The bus climbed above valley inversions, and the mountains surrounding Blacktail appeared as "islands" in an ocean of clouds. The bus would get stuck behind a resident moose. Why didn't the driver honk the horn? He tried that once; the moose tore the radiator off the bus.

He came to the Flathead with his wife, Gayle, to whom he is still married. Montana impressed the newlywed couple as the kind of place they would like to settle down. Reid had wanted to be a writer since elementary school, but didn't know where to begin. After the Air Force, he majored in geography at the University of Illinois in Champaign. There, he took his first creative writing class. His professor demystified the art. "It's like you are a mechanic," Reid realized, "and there are tools you can learn how to use". Because it was the only MFA program he had ever heard of, he applied to the Iowa Writers' Workshop. "They sent me back a nice letter that said, basically, it's real hard to get in here. You probably can't because, really, nobody can...unless they're struck by lightning. Here's a list of all the MFA programs in the country". In that directory: The University of Montana.

Reid still listens to recordings of local bands like the Mission Mountain Wood Band and Big Sky Mudflaps, popular when he studied writing at UM. The music reminds him of Montana's freeness and easiness, especially during his early years here. He's never fallen out of love with the landscape. There can't be another morgue in the world that has a view like this, he thought once: An investigation brought him to an autopsy on a day you could see into the Bitterroot Valley from the sixth-floor morgue window of the old Saint Patrick's Hospital. And Reid doesn't mind the long, gray Missoula winter. Though he admits, "February in Missoula separates the truly despondent from the merely depressed".

Nature is a redemptive force in Reid's fiction and life. For rejuvenation, he goes where there's, as he put it in one of his novels, "no city, no story". But, "the green of a thousand million trees, and the brown of rocks and of late summer grass and hidden elk, and the smart blue and white of sky. And silver. The silver of lakes". Reverentially, he tells of backpacking with his grandson in the Rattlesnake and awakening just after daylight to find a black bear sow with two cubs, watching them from high in a tree.

Right after graduating from Illinois, Reid wrote an inquiry letter to William Kittredge, then head of UM's MFA program. Kittredge wrote back, explaining the application procedure. "But don't just come out here," Kittredge told him. Reid disregarded. Upon his dead-of-winter arrival, he walked into Kittredge's office and introduced himself. "You said, don't come. But here I am".

"Well," Kittredge said, "you might as well start coming to class now," and Reid audited creative writing courses until official admission into the program. The '70s were a golden age for the University of Montana's MFA program, when, besides Kittredge, Madeline DeFrees, Earl Gantz, and Richard Hugo taught graduate-level creative writing. "He was a very nurturing teacher," Reid says of Hugo. "You know, he would never just tell you something was awful". Hugo might instead "look at you over his glasses and say, 'I'm not quite sure what this means, but it's very interesting'". Reid connected with Kittredge, too, who imparted the wisdom that the piece is not done until you have deleted your favorite line.

Reid was something of an outlier in his cohort. When he started graduate school, he had been married to Gayle for several years. They had a young daughter. He was older than many of his classmates and not as "free or loose". He didn't have time to socialize. He managed the World Theater, an old-time single-screen movie house near campus. It's the building on South Higgins that collapsed under the snow in 2017.

These days, Reid golfs some. He plays bagpipes in Missoula's Celtic Dragon Pipe Band. He works on his yard and house, reads broadly, spends time with Gayle and a young labradoodle, and has coffee fairly often with fellow writer and Missoulian Jon Jackson. His retired lifestyle is hard-earned. After a devoted public safety career, working patrol, as a detective, a sergeant in crime analysis, as administrative captain, then as Missoula County's director of Disaster and Emergency Services, when Reid retired, he retired.

TV shows fail to capture how exhausted detectives are all the time, he says. When a show depicts evidence collection, for instance, "they'll have all these technicians that do all of this work, a team, and they'll have 10 people working for them. Well, in the '80s, there would be two of us that did all that work".

Reid was also a founding member of Missoula's hostage negotiation and crisis team, formed in 1982. A 1996 Missoulian article details a harrowing 77-hour standoff between law enforcement and a man who, violating an order of protection, invaded the home of his estranged wife and daughter with a gun, knife, leather straps, chains, and padlocks. Reid was the city's senior hostage negotiator at the time and led the negotiation effort.

Before joining the Missoula Police Department, he completed his first novel, the coming-of-age story Max Holly, and attempted to sell life insurance. This sales position held no enchantment for him. He needed a new job. Law enforcement seemed interesting enough. "I could get someone to confess," Reid says, "but I couldn't sell anyone life insurance".

Reid describes law enforcement as a blue-collar job, in a good way, when he started in the early '80s as a patrol officer. Many don't realize that the job is often routine and boring. Reid says when he'd work the county fair, he'd field enough of the same questions from kids to hang a sign around his neck that said, "It's a .357. I've never shot anyone. The bathroom is that way". Bad things do happen on the job, of course, but it can be fun. Comical encounters abound. Many people worry about the physical danger, but he believes the greatest threat to patrol officers "is all those hours that you spend alone in a car, in the middle of the night, riding around brooding over things. You can become dangerous to your mental health in that way".

He captured these realities in his second novel, Big Sky Blues. The job's emotional hazards are more adversarial to the cop characters than the story's violent perpetrator, a bedraggled vagrant named George Rather. It's the first of Reid's novels to take place in fictional Rozette, Montana, with similarities to Missoula, when the mills and wood stoves caused smog and the Oxford still served brains and eggs. Secondary characters you feel you have encountered in Missoula populate Rozette. Take, for example, Pastor Roscoe Beckett, who is not a pastor. In a Harley-Davidson tank top with a bushy beard and ponytail, addressing anyone he talks to as "Jim," Roscoe's the kind of guy you meet at Charlie B.'s before noon, at the counter of a fusty downtown junk store, or fronting the Friday night band at the bowling alley.

Unlike his characters, Reid doesn't curse much. He laughs as he recounts a time he went back to Illinois. He attended church with his family. The minister introduced Reid to the congregation. The minister said he hadn't read any of his books, but understood the language was pretty bad. Author James Crumley blurbed Big Sky Blues as perhaps the finest police novel he had ever read. "Bob Reid is a wonderful writer—he's got a real gift for language balanced by a deep sense of humanity," Crumley told the Missoula Independent in 1994. "And he's a great guy. He's the kind of cop you'd like to have around if your family were in trouble".

Despite living in two different worlds and not socializing much, Missoula's literary wild man, Crumley, and Reid became friends. Unlike Reid, Crumley liked the limelight. For Reid, publication proved an artistic victory, but he found it "conspicuous". At first, other officers kept him at arm's length for fear they would wind up in a book. They learned, however, that Reid is loath to incorporate people he knows or cases he has worked into his writing. He does not believe the homicides he has investigated, for example, are his stories to tell. "I was involved in people's lives at the worst time in their lives, you know?". He sees using such experiences as too much of an indulgence.

He never wanted to turn himself into a commodity, either. "That doesn't bode well for marketing in the modern world," he says. But Reid is a good sport. So, he frequented readings, spoke on panels, appeared in a French documentary, and on CBS's Top Cops.

Reid tries something different with each new project. He learned that publishers consider this a curse. Publishers want one book that people will buy with variations to follow until they don't sell anymore. He understands books are a tough business. Pigeonholes are necessary to keep lights on and people employed, but they can stifle creativity.

In recent years, Bob and Gayle walked the 84-mile Hadrian's Wall Path through England. The trail follows the protective military wall built by the Romans in the first century. The experience galvanized Reid to compile research and write a creative nonfiction book. He now pursues its publication. "That'll be just a matter of how much despair I can endure," he jests. He has also returned to a novel he started years ago. Its narrative sweeps back in time to World War I and traces a life through the twentieth century.

Regarding Rozette's enforcers and malefactors, Reid believes he has said all he had to say. He succeeded at what he set out to do—compellingly cast police characters as ordinary people, doing their best at a hard job unlike any other, when everyone outside the job thinks they know more about it than those working it.

And he wrote the Montana he saw. For all Western literature's transcendent fly-fishing sessions and sublime auburn sunsets, he balanced with, say, inclement weather and human corruption. Besides crime fiction, Reid is well-versed in writing poetry, literary fiction, and, now, nonfiction. Writing has been a consistent force for most of his life. No matter the genre, he still revels in making something out of nothing. The process entails discovery, and for Bob Reid, that is something beautiful. After over fifty years, he still loves letting a scene rip, not knowing exactly where it's going, and discovering something about a character or maybe even life itself. He'll take that over carving out a niche for himself in the market.

On a beautiful day in Missoula, the home he has loved, protected, and served for much of his life, he says, "Nothing is more fun, at least for me, to read back over something and just stop. I can't believe I said that, you know?" He quips that there's a flipside: "I can't believe I said that," either.

Leave a Comment Here