The Montana Circle of American Masters

The brainchild of the Montana Arts Council in Helena, the Montana Circle of American Masters recognizes the lifetime accomplishments of artists across the state who keep cultural traditions alive through their work. From quilters to sculptors, canoe builders to beaders, nominees are evaluated each year based on a number of criteria, including mastery of their craft, an understanding and respect for the cultural heritage represented by their art form, and their role as teacher and mentor in their communities. Seven master artists were inducted into the Circle last spring at the Capitol, including Apsáalooke cowboy poet Henry Real Bird and Salish lifeways keeper Tim Ryan. These inductees joined the ranks of over 50 craftspeople who together represent the diverse artistic and cultural traditions practiced in Montana.

Distinctly Montana spoke with three master artists about their respective crafts and creative paths. Their stories speak to the levels of persistence and playfulness demanded by creative pursuits, and to the ineffable satisfaction to be had through honing one's craft.

DEB ESSEN, HANDWEAVER

Owner of DJE Handwovens, Deb Essen has been weaving for over thirty years and teaching her craft for nearly as long. Hailing from Minnesota, Deb aspired since childhood to learn the art of handweaving, and began spinning yarn and weaving through the Minnesota Weaver’s Guild before moving to Montana in 1996. Once nestled in the Bitterroot with her family, Deb delightedly found herself in the company of skilled fiber artists in every direction.

Over the course of two years, she worked toward the first level of Certificate of Excellence through the Handweavers Guild of America, an experience that honed her skills in weave structure, design, and the application of color theory. She enjoyed it so much, she continued onto the second level and eventually wrote her first book, Easy Weaving with Supplemental Warps, which was published in 2016 and expanded and republished three years later.

The joy Deb finds through her own learning process was also what inspired her to start teaching. She puts her natural inclinations for structure and color experimentation to use as a teacher, putting together starter kits for students that include a textile design, warp (the fibers stretched onto a loom through which the remaining fibers, or weft, are woven), yarn, and directions. "I found early on that I am NOT a production weaver who puts on a seven-yard warp and weaves ten dish towels," Deb writes. "My love is creating the design and weaving up about 18 inches so I can see how it looks and then I actually have to talk myself into weaving the rest of the project!"

Deb’s willingness to experiment is key to her artistic development, but she also credits her growth to Montana’s weaving communities. Suffragist Mary Meigs Atwater is credited with the revival of traditional handweaving in the United States, an endeavor that started here in Montana. While living in Basin around 1916 where her husband ran a mine, Atwater researched traditional weaving patterns from Appalachia, wrote books on the subject, and taught what she learned to other women in Basin as a means of fostering their economic independence. She also started publishing the Shuttle Craft newsletter and correspondence course and helped found eight weaving guilds throughout the state, the Missoula and Helena branches of which have operated continuously ever since. Visible threads run between Atwater’s early correspondence courses and Deb’s own teaching methodology, with the kits that she mails to students across the country.

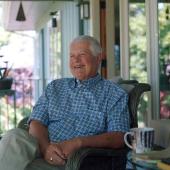

MIKE RYAN, BOOTMAKER

Mike Ryan started making custom boots in 1985, when he attended a five-and-a-half day school under the tutelage of carpenter-turned-bootmaker Mike Ives in Lockwood, an unincorporated community on the banks of the Yellowstone. Those five and a half days were the only formal training that Mike Ryan ever received in his trade, and he walked out the door in the boots that he made that week. "They’ll probably set these up at my funeral," he says in a tone of both pride and amusement, as he holds up the boots for the camera.

Born on a ranch in Brusett, about forty miles northwest of Jordan, Mike aspired at the age of sixteen to buy Jordan’s only boot repair shop from its owner, Lloyd Burchett, a man who after a childhood bout with polio wore a brace on one leg. At seventeen, Mike deployed to the Navy and served in Vietnam. When he returned home, Burchett had already sold the business, so Mike got a job at Al’s Bootery in Billings, where half his wages were paid by the GI Bill and half by the shop’s owner. Mike recounts that he fell right into the work from the beginning, even before his training in Lockwood—so much so that his supervisor, a one-legged man "with a wood stob at the end," accused him of being "a lying son-of-a-b" when Mike said he had never worked in a shoe shop before.

"It’s a lot easier to do a thing if you’ve got a knack for it," Mike says now. "It’s a lot easier to do something if you understand."

Mike’s shop, where he raised both his children "because I was too cheap to hire a babysitter," holds a plethora of hand tools and machines. Some machines can be used for both custom and repair jobs. The post machine, for example, does a much more precise job of patching than a dedicated patch machine. Other machines are good for one task only, such as the zigzag machine used for sewing together the back of lace-up shoes. "Very seldom do I ever zigzag anything," Mike says. "I’m not much of a zigzagger."

He explains that some boots are made the same as they always have been—leather uppers, wood-pegged soles—but a lot of brands have switched from leather to hard plastic, which makes repairs more difficult. There are some repairs he won’t even attempt, because he knows from decades of experience that it’s hopeless—dog-eaten shoes, for example, are almost always beyond repair, and a sign on his shop’s front door states as much.

There will always be people who prefer to fix their shoes, Mike says, rather than throw them away and buy new. This desire is what keeps him in business, but at the same time, "I don’t have time to explain for fifteen to twenty minutes why something can't be done. If it can’t be done, it can’t be done. It’s that simple."

Mike moved to Helena in 1986, when there were five shoe repair shops in town, although even back then, he was the only bootmaker. He’s now the only shoe repair place left, and has over the course of his career made over 5,000 pairs of boots for hundreds of people all over the country.

"I retired nine years ago," Mike explains, "so I’m not taking any new customers. But an old custom boot customer comes in and wants a pair of boots, I’ll do it. And now what they’re doing, some of my old customers will come in and say, 'You know, I think I’ll order two pair. That way if you die, I’ll have two more pair.' So I’m running into that now. The older I get, I’ll probably be making three pairs at a time." He laughs, and affirms, "I’ll keep doing it the rest of my life, I guess. Gotta do something. And I enjoy it, so why not do it?"

GLENN GILMORE, BLACKSMITH

On a cross-country road trip in 1970 back to his home in Michigan, Glenn Gilmore stopped for a few days in New Mexico, where he helped his cousin forge horseshoes on the family ranch. Over the next fifteen years Glenn took farrier classes, attended conferences and workshops in the art of forged metalwork, and eventually made his way to Germany and Belgium, where he apprenticed with artist-blacksmith Manfred Bredohl for several months. He has since built a career in forging site-specific installations for clients across the country, from custom fireplaces and furniture to banisters and home hardware.

Glenn describes his time with Bredohl as a "revelation" in his creative path, one that he didn’t realize was happening in the moment. He transitioned under Bredohl into using bigger pieces of metal, and his natural proclivity for detail shifted from an exclusive focus on forging technique to the artistic details of the pieces he was creating—a focus, for example, on the textures and visual flow of the joints involved in forging tree branches. Bredohl taught Glenn that the more you produce, the more you see what is possible—in other words, "work comes from your work." Bredohl also taught his students to enjoy the process of producing work. "When you’re happy with what you do, your customers can see it in what you’ve made," Glenn says.

Glenn moved to the Bitterroot 25 years ago, where he works out of a forty-by-forty-four-feet studio integrated into his home outside Victor. While he continues to travel across the country for installations, Glenn makes it a priority to teach closer to home. He opens his studio to tours, and has held demonstrations for high school students enrolled in welding classes in Corvallis.

"Being a studio artist is a lonely world," Glenn says, and opening his workspace to students gives him a boost of energy and a renewed appreciation for his own craft. "When you teach, you have to think about your work," Glenn explains, "which then compels you to rethink your work." He plans to host a series of blacksmithing classes in 2026.

- Reply

Permalink