A Long-Ago Winter in Blackfeet Country

Old Montana families remember the winter of 1886, when the cattle herds in eastern Montana were nearly wiped out, as memorialized by Wallace Stegner in his book Wolf Willow, and most everyone has heard about the record-breaking cold atop Rogers Pass in 1954, when the thermometer maxed out at -70 degrees. Journals from the 19th century make clear that winter isn’t what it used to be.

Accounts of the Mullan Road construction crew tell of unimaginable hardships due to extreme negative temperatures, snow, ice, and relentless wind. Conditions around Cantonment Jordan, now De Borgia, Montana, were especially harsh. On December 5, 1859, the temperature plunged to 42 degrees. The snow was five feet deep in December, and two feet deeper in January. Men suffered the consequences of frostbite, even the loss of limbs. The next winter, at Cantonment Wright, built at the confluence of the Clark Fork and Blackfoot rivers—now Bonner—snow began falling on November 1 and daytime temperatures rarely reached above 0°F. The cold was exacerbated by strong arctic winds drawn through the valleys from the east. In Missoula, these wintertime visitors are known as the dreaded Hellgate winds.

The following winter was as bad or worse according to journal entries by John Owen, Bitterroot Valley trader, based at what is now Stevensville. On February 11, 1862, describing "unusually Sever & tedious" winter conditions, Owen wrote: "We are Nearly Surrounded with the Water from Mill Creek caused by the intense Cold freezing the Creek Nearly to the bottom leaving No Channel for the Water to flow through." These conditions continued. A week later, Owen noted that "cattle & horses dying in groups of from 3 to 10 Every day." Not only domesticated creatures died, but presumably also deer and elk, and other wildlife, during those horrific months in the tributary valleys of the Clark Fork and throughout the region.

On the Columbia Plateau, some five hundred horses perished in a little valley where they had sought shelter. Tightly huddled together, "a sheet of one mile square would have covered all of them, frozen fast where they tried to paw and stand, with little to be seen of them in the deep icy snow." Weather on the buffalo plains east of the Continental Divide was no better. Granville Stuart reported that the Salish had "suffered terribly while hunting across the mountains." They lost most of their horses and were unable to kill many buffalo, consequently, they were without meat and were in a starving condition.

By the spring equinox, Owen summed up the winter as "one of unprecedented severity..." Francis Lomprey (Lumpré), a French trapper and interpreter, visited that winter. He had been in the area for some two decades and he told Owen "he never Saw the like."

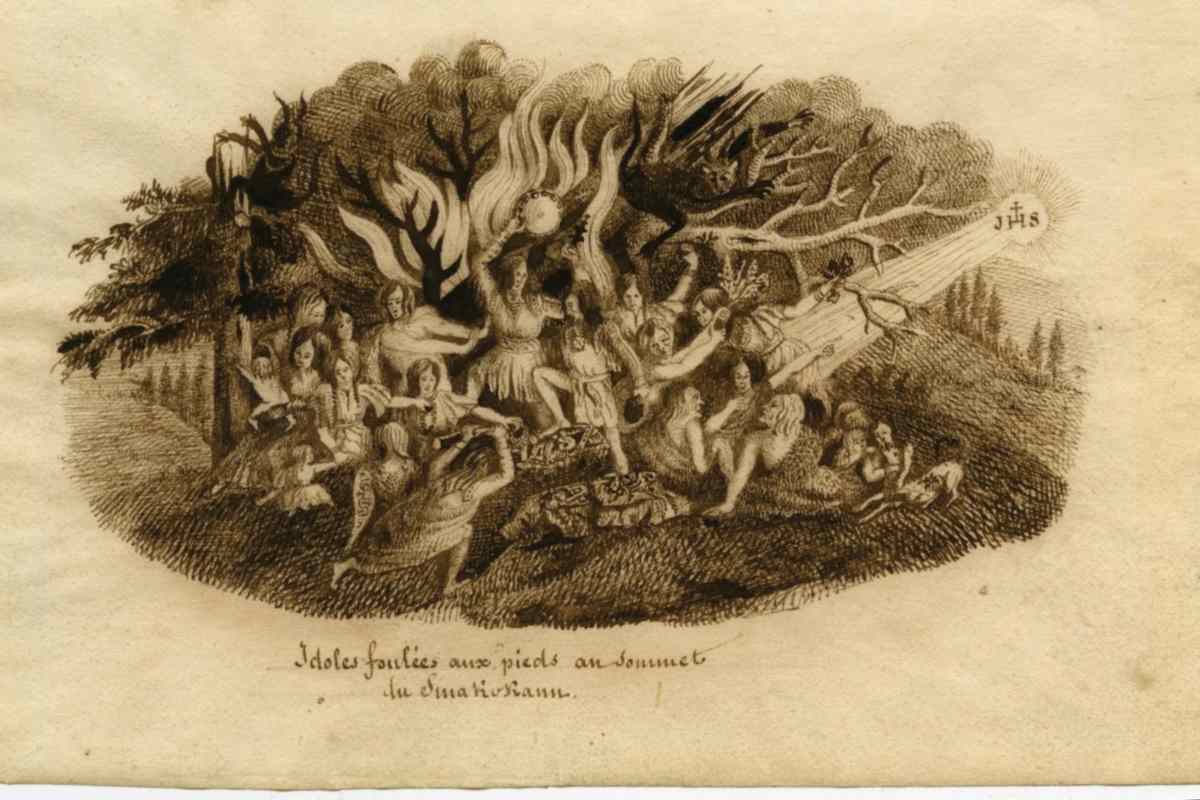

Perhaps old Lomprey had forgotten the similarly harsh winter of 1846-47, when even bison died from the cold. Near what is now Phillipsburg, more than one hundred of the shaggy beasts froze to death, stranded in deep drifts of the upper Rock Creek country. That same winter, Jesuit missionary Nicholas Point endured terrible conditions while in the country of the Blackfeet. He wrote about it in his journal, published as a coffee table book called Wilderness Kingdom in 1967.

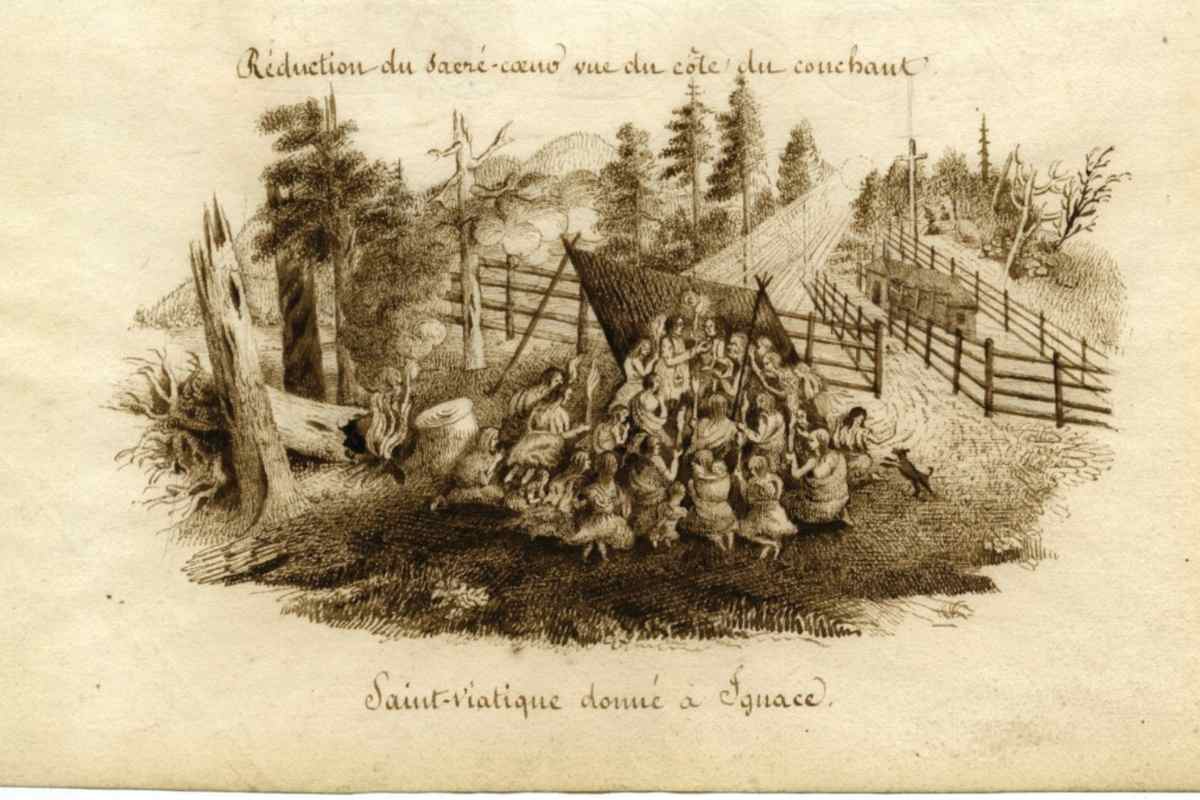

This French missionary had traveled with the famous Black Robe Fr. Jean Pierre De Smet from Coeur d’Alene Mission, on the west side of the Bitterroot Mountains, to the Musselshell Country and on to the new American Fur Company post called Fort Lewis, on the Missouri River, across from what later became Fort Benton. The priests proselytized among the Blackfeet that August, before De Smet headed down the Missouri to St. Louis, leaving Father Point behind to teach and baptize.

Point made friends with many tribal leaders through his artwork. He would sketch their portraits and allow the men to keep them as tokens of friendship. They, in turn, invited him to visit their camps, scattered throughout the area, where he could teach them more about his religion.

One of these men was a middle-aged leader of the Blood (Kainai) Tribe of the Blackfoot Confederacy named Peenaquim, "Seen From Afar," who was part of a family that was quite influential among the Americans. He was the brother of Natawista, "Medicine Snake Woman," the wife of the head trader on the Upper Missouri, Alexander Culbertson. Peenaquim and Natawista were the children of Two Suns, Chief of the Fish Eaters band, with a following of some 2,500 people. Peenaquim, whom Point called Panarquinima, insisted that Point visit him at his camp and the missionary assured him that he would.

However, the invitation was stymied by various obstacles until, finally, in late December, he grabbed the opportunity to travel with the fort’s very young chief interpreter, who was to carry a message from the post to the Fish Eaters. They traveled a distance of "three or four hours of trotting and galloping" to arrive at Peenaquim’s camp of 100 tipi lodges.

The warmth of the fire in the middle of Peenaquim’s tipi was like a welcoming embrace, after their bone-chilling journey. The wind glided past the conical form, much like a stream flowing around a boulder, and with its thick hide cover, the lined lodge stayed warm enough to keep water drinkable for the men as they ceremoniously greeted each other by passing the pipe that day. Peenaquim rested atop a bed of rich furs in the place of leadership across from the east-facing doorway.

Apparently Point was highly successful in communicating his intentions for them to adopt Catholicism, for he was allowed to conduct over 100 baptisms of children. On his final day there, he baptized the last children "in the open air, as the lodges were being folded up" in preparation for moving to a new location. With no protection from the cold, he reported conditions so intense that the baptismal water froze between his fingers as he attempted to apply it to their little heads.

We don't know just where the Fish Eater camp was located because Point had little geographical sense. We do know that their return to Fort Lewis was challenging, especially crossing the Missouri. The adventuresome missionary wrote that "This crossing could be dangerous because the current does not always permit the ice to form solidly. In such cases one usually used a probe to try the ice." In his typically understated manner, he noted that "In the absence of such an instrument, one does the best he can, which is what we did," and they managed to arrive safely.

From their base at Fort Lewis during that winter, Fr. Point and his young interpreter visited scores of camps on foot. Travel was easier than in December because the rivers were soundly frozen and "the ice formed solid bridges everywhere." The camps were so densely settled that on one day, between breakfast and supper, they visited eleven different camps, both Gros Ventres and Blackfeet.

The missionary learned about some winter survival strategies. The Gros Ventres told him they relied on wolf hides for caps, scarves, and mittens. In this region, people lined their thick-soled hide moccasins with rabbit fur in winter, or with the fine textured leaves of sedges, if fur was not readily available.

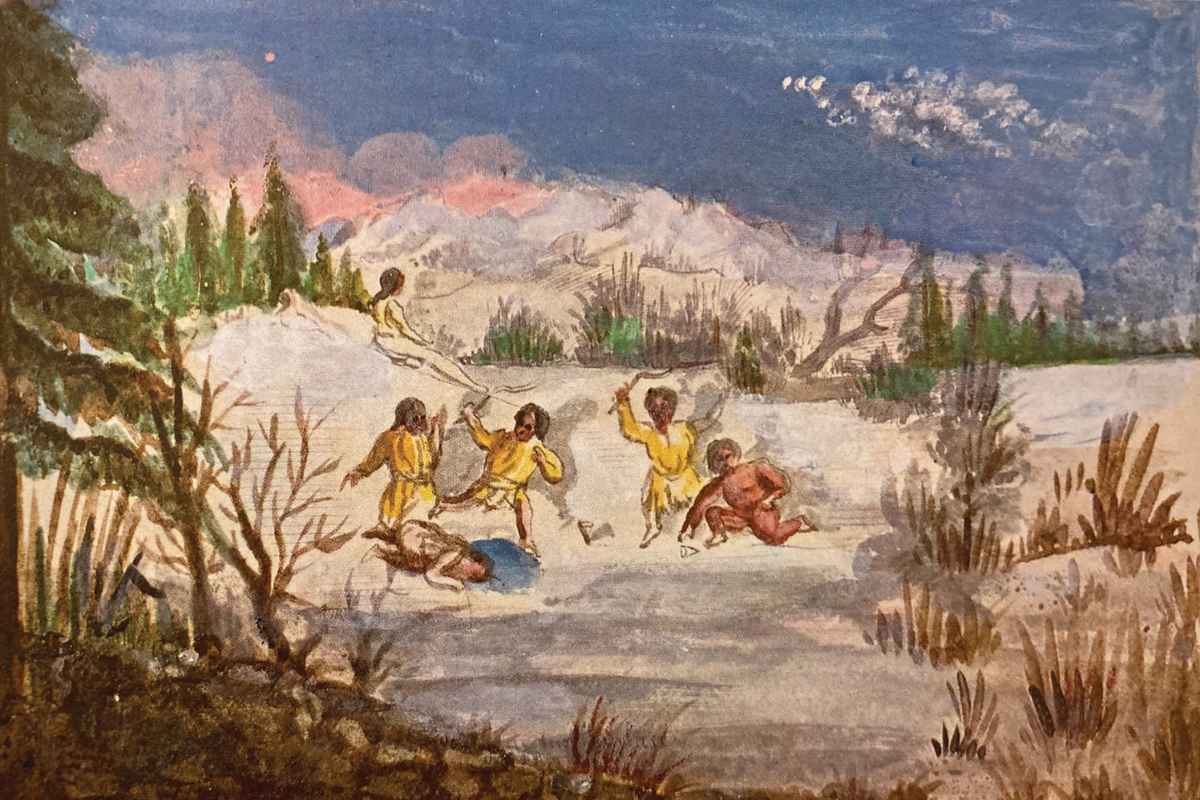

Children were surprisingly active during the cold winter days. Father Point was particularly struck by their various games. One especially compelling sight was to see children on little wooden sledges careening down the frozen mountain "with astonishing speed." Others were seen sliding over the ice, "standing straight as candles." The missionary noted some of the children, bent over holes they had broken in the ice, where they were "dabbing their hands in the cold water." Perhaps they were fishing? Another game involved spinning tops by stroking them with "birchrod" sticks to keep them going.

Around the time dawn was emerging from an extremely cold February night, the sky around Fort Lewis lit up with a perfectly formed cross. "Its beams were red in color just as the much larger disc that framed it. The extremities of the vertical beam were contained within this disc, but the horizontal beam stretched out along the horizon." The missionary, no doubt, was trying to capture the details so that he could later paint this celestial display which was described to him by others. He had missed the event entirely.

He noted that the "small equidistant, concentric rings of different and various colors" arranged along the horizontal line, "at points where it intersected the circumference of the disc... it intersected still another circle made visible only at these points of intersection." He noted that "the local physicists (among the Indians) call these rings buck-eyes." He learned from them that "they have seen similar phenomena many times before," but this was the most dramatic. They also told him that these manifestations only occur at times of extreme cold, but he wondered if it might result from more than frigid weather.

To him, the description suggested something more than "a paraselene," which Merriam-Webster defines as "a luminous appearance seen in connection with lunar halos." From people at the fort who saw it, and also from travelers who arrived the next day, he drew the conclusion that they had witnessed "a cross on the solar disc at sunrise, an event which does not appear in ordinary parahelia" (sun dogs).

For him, this display was a miracle, a "sublime sign of our redemption." The next day, "to preserve the memory of all of these events so glorious to Catholicism," the missionary, with the help of the children of the fort, built a stone pyramid over the grave of a child who had been buried that day. He placed a wooden cross atop the small pyramid and hoped that future generations of Blackfeet would look upon the "little monument" and recall "the goodness the Lord did for their forefathers during the year 1847."

A spectacular example of the phenomenon Point described occurred in Sweden on December 1, 2017, and was captured by meteorologist Seth Phillips. He described the event as consisting of "two sun halos (22' and 46'), a tangent arc, a sun pillar, parhelic circle, and parahelia (sun dogs)," noting how rare it is for all of these to occur simultaneously. "When it does, it is the crème de la crème of atmospheric arcs!" He explains that these arcs form "when ice crystals high in the atmosphere are in the perfect place for the observer to see the sun’s light refracted." These atmospheric optics occur on sunny days when cirrus clouds occur high overhead. The sun dog is one expression of solar halos. Like the one that occurred at dawn in 1847, they are most visible when the sun is near the horizon on extremely cold days.

To my knowledge, the little monument no longer exists, and the Blackfeet lost access to this area many decades ago. But the Montana plains along the high line still suffer the occasional deep freeze. The next time you find yourself complaining about the cold, think again. Be grateful for central heating, insulation, and all the ways we are protected from its impacts. You might also pause and give some thought to the intelligence and stamina it took to survive in these parts long before we were born.

Leave a Comment Here