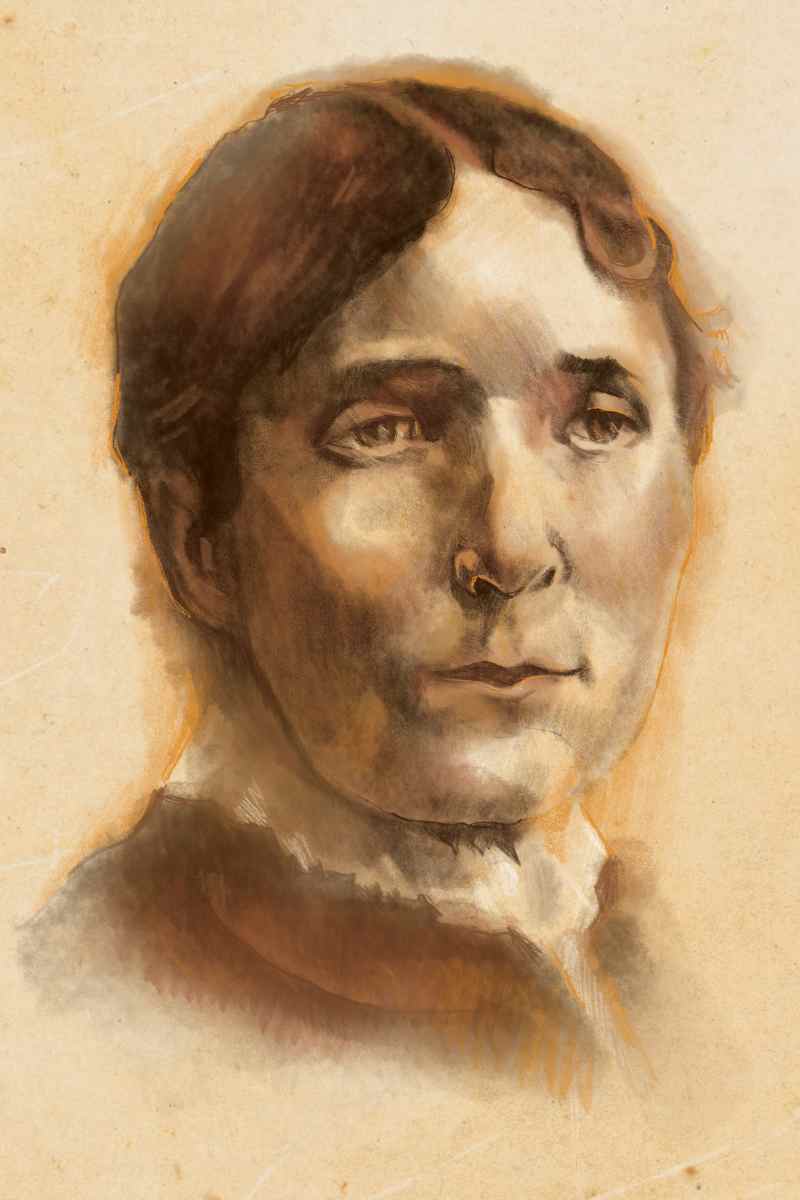

Lucia Darling, Montana Teacher

The sprawling mining community of Bannack, Montana, was awash in the far-reaching rays of the morning sun. The rolling hills and fields around the crowded burg were thick with brush. Saffron and gold plants dotted the landscape, their vibrant colors electric against a backdrop of browns and greens. Twenty-seven-year-old Lucia Darling barely noticed the spectacular scenery as she paraded down the main thoroughfare of town. The hopeful schoolmarm was preoccupied with the idea of finding a suitable place to teach.

Escorted by her uncle, Chief Justice Sidney Edgerton, Lucia made her way to a depressed section of the booming gold hamlet searching for the home of a man rumored to have a building to rent. Referring to a set of directions drawn out on a slip of paper, Lucia marched confidently to the door of a rustic, rundown log cabin and knocked. When no one answered right away, Chief Justice Edgerton took a turn pounding on the door. Finally, a tired voice called out from the other side for the pair to "Come in."

The interior of the home was just as unkempt as the outside. Cobwebs clung to the dark corners, dust inches thick covered dilapidated pieces of furniture; mining equipment, picks, pans, and axes were scattered about as well as a few dirty clothes, and an assortment of whisky bottles. A pile of buffalo robes in the middle of the floor stirred, and a scruffy prospector, obviously suffering with a monstrous hangover, emerged. Lucia and the chief justice introduced themselves and informed the man that they were there to look at some property he owned that could possibly be used as a schoolhouse. "Yes," the miner responded with a thick tongue. "Damn shame, children running around the streets here. They ought to be in school. I will do anything I can to help. You can have this room."

Lucia gave the man a polite smile and made her way around the room examining the space. Eager to come to an arrangement, the miner reiterated his belief that children needed to be educated and reaffirmed how willing he was to make that possible. The moment Chief Justice Edgerton asked about the price the man began tidying up a bit and cursing about the state of the space. "Well, I'll do anything I can. I'll give it to her cheap," the miner assured Lucia and her uncle. "She shall have it for $50 a month. I won't ask a cent more. It's dirt cheap."

The chief justice thanked the man for his time, and he and Lucia exited the crude dwelling. The persistent prospector stood in the doorway repeating his desire to be generous and help the children. "Fifty dollars a month for a broken-down structure that had mud plastered walls inside and out, a mud roof and dirt floors?" Lucia said to her uncle as she shook her head. "I believe his generosity extends only to himself," she added under her breath.

Lucia had begun her search for a classroom in late September 1863. After turning down the greedy prospector's offer, she spent another month trying to locate a suitable facility. Due to the exorbitant cost of renting even the most modest space, Lucia decided to teach school from her uncle's sizeable and comfortable home. "The school was opened in a room in our own house," Lucia remembered in her journal, "on the banks of the Grasshopper Creek near where the ford and foot bridge were located, and in hearing of the murmur of its waters as they swept down from this mountain country through unknown streams and lands in the distant sea."

Lucia Darling's desire to become an educator began when she was a young girl growing up in Tallmadge, Ohio. She was born in 1839 to dedicated farming parents who did not place as much emphasis on learning to read and write as they did the ability to complete chores. Lucia did, however, excel at reading, history, and math, and passed along what she knew to her brothers and sisters. When she was old enough, she received the proper training necessary to become a qualified teacher.

After more than nine years of service in the area of northeast Ohio and teaching at Berea College, the first interracial college in Kentucky, Lucia decided to travel west. Educators were woefully lacking in the western regions, and she hoped to build and grow a frontier school wherever she settled.

On June 1, 1863, Lucia gathered her belongings and left home with her uncle, Sidney Edgerton, and his family and headed to Lewiston, Idaho. Edgerton was a politician, a representative from Ohio, who had been appointed U.S. judge for the territory of Idaho. The estimated three-month-long trip was being made so he could take over the position. Although Lucia would not have a group of children to teach while on the trail, she wanted the trek to be educational for her future pupils. Throughout the entire journey Lucia kept a detailed diary. The diary outlined the route they took, the Indians they encountered, the historic landmarks they passed, the daily chores that had to be done, and the weather patterns.

Lucia and her family started their travel via railroad from Tallmadge to Chicago, then on to Quincy and St. Joseph. From there they boarded a riverboat and floated along the Missouri River to Omaha. Lucia described Omaha as an "isolated frontier town, built largely of logs with few houses more than one story in height. The great territorial capital of the bluff looked down upon the little hamlet, keeping over its citizens, watch and ward."

The trip from Omaha west was made by covered wagon. As was customary, the party was joined by other wagon trains heading in the same direction. Lucia introduced herself to the members and hoped they would all become fast friends. The wagon train would venture more than 500 miles across the vast prairie to its final destination. One of Lucia's first journal entries describes how exhausting the trip would be to make:

"June 16—Our camp life has commenced and I am lying here on my back in a covered wagon with a lantern standing on the mess box at the back end of it. Have pinned back the curtain so as to let the light shine in but it is so situated that I have to hold my book much above my head to see. Will write 'till the light goes out. We left the Herndon tonight after tea our wagons having gone on some hours before. Most of the oxen are young—never having been driven before and they were determined to go every way but the right way. The drivers—Gridley, Chipman, Booth, and Harry Tilden were completely tired out trying to drive them. They scurried perfectly wild and ran from one side to another of the road, smashed through fences and finally broke one yoke in pieces."

Poor weather conditions posed numerous problems for the pioneers. Learning how to keep precious belongings safe from a light rain as well as keeping food dry during torrential downpours wasn't an easy task. According to notes Lucia made in her journal in mid-June 1863, a storm hit just as the sojourners were preparing to set up camp one evening:

"June 17—Wednesday. We truly had quite a time yesterday and today has been a continuation of the same thing... Went about three miles and camped on a small creek for the night. Uncle Edgerton and Gridley guarding the cattle. We hardly had time to get our things ready for the night when it commenced to blowing terribly the thunder and lightning indicating a dreadful shower. Here I stand with my back against the front curtains of the wagon to keep it from blowing in and writing by the light of the lantern I have hung out to let those who are out guarding know where the camp is. The wind is blowing a perfect hurricane and every gust threatens to take off the wagon covers. The occupants of the tent find it more than they can do to keep it upright. The situation is quite alarming. The lightning at every flash seems to envelop us in a sheet of white flame and the rain pours in torrents."

Everyone on the train had specific jobs for which they were responsible. Some cared for the livestock, others gathered wood and tended to the children. On June 21, 1863, Lucia took a moment to give an "account of everyday pioneering life" and outlined some of her own duties:

"June 21—The first thing in the morning of course is breakfast and as Aunt Mary and Cousin Hattie are busy with the children that duty mostly falls upon me with Amurette's help. I usually find the fire built in the little stove standing at the back end of the wagons and as there is only one course at breakfast it does not take long to prepare it—coffee, ham, or bacon, biscuit, or griddle cakes or both, gravy and plenty of milk. Before setting the table it has to be made each time by taking the boards from the front end of the wagon and placing one end under the back part of the corner of the mess box which is sloping, and letting it rest on the front side of the box make it nearly level. Three of these boards form quite a table on which we put a tablecloth, tin plates and cups, knives, forks, spoons, etc. The milk is strained into a large tin-can and hung under the wagon. Our wagons are so arranged that the things can be put back from the front during the day and chairs can be set in or we can sit or lie down on the bed at the back of the wagon. The wagon covers have been a good protection from the sun thus far. We make a stop of an hour or two at noon and then try to get into camp in time to get supper and do up the work, get the cows milked and the tent pitched before dark."

On July 3 Lucia and the other party members crossed the Platte River, and it was on the other side of the river where they had their first encounter with Native Americans.

"Heard the startling news that only five miles below us there were fifteen hundred Sioux Indians. They had come out to fight the Pawnees so we did not fear them much. We should be perfectly powerless if they had attacked us, but they did not, and in fact we see no signs of Indians nor have we but once since we left Omaha."

By July 16, 1863, the wagon train Lucia was a part of reached Chimney Rock, the most famous landmark on the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails. Nearly half a million westbound emigrants and other travelers saw the monument en route to the West Coast. Many of those emigrants drew sketches of Chimney Rock as they passed. Lucia was content to write about the stone formation in her journal:

"July 16—Thursday. Next noon came in sight of the renown Chimney Rock and the first sight of it was really like a chimney. The atmosphere was smoky and made the rock seem more like a large chimney from some great manufacturing establishment. From which the smoke had settled down over the surrounding country. It seemed quite near us when we camped at noon and Hattie and I were determined to go over it but all said we were crazy, we could never get there however we started with Henry and Wilbur with the pleasing assurance from Mr. Booth that it was seven miles at least."

In the midst of the hardship of frontier travel, Lucia and the other members of her party found ways to enjoy themselves. They collected wildflowers, swam in swift, cold riverbeds, and in the evenings around the campfire some pioneers played musical instruments while others sang and danced along.

On August 13, 1863, the wagon train stopped at a small military camp of twenty Ohio soldiers. A celebration of sorts was held that night to welcome the emigrants to the scene.

"We are in camp near their barracks and they seem very glad to see anyone from the States. A soldier's life here is very monotonous and very uncomfortable in winter. During the evening, the soldiers came over and sat around the stove and Mr. Everett brought over his violin and we had a swing. After we had finished singing the soldiers danced a cotillion or two which they entered into with energy."

On a good day, the wagon train could travel between fifteen to twenty miles. When the day's journey ended, people took turns guarding the vehicles and livestock in the evenings. On September 3, 1863, Lucia stood in as a lookout for her uncle:

"I sat up and watched the cattle and the stars all night with our Indian pony for company. The number of Indians and bears I saw on each side of the camp among the willows in the moonlight I did not count, but have decided today in broad daylight that it was all my imagination. Uncle set his gun out of the tent and I kept my revolver close to me. Wonder what I would have done if I had seen one, either a bear or Indian I presume I should have screamed perhaps not."

The driven schoolteacher arrived in Bannack, Montana, in mid-September 1863. An onslaught of winter weather kept the wagon train from moving on into Idaho. It was decided that the pioneers would stay there until spring. The drive west had been a trying one for Lucia, but the sight of a civilized town after three and a half months on the trail made her temporarily forget the struggles.

"In looking back to that journey from Ohio, I think of nothing that interested us more than our arrival in Bannack. The growth of a city whose existence and fame went hand in hand and spread over the entire continent in a single season."

Bannack was a wild and wooly gold-mining town. It was founded in 1862 by a prospector named John White who dipped his pan into nearby Grasshopper Creek and came up with chunks of glittering yellow rock. News of the rich gold deposits in the area spread quickly. Miners, businessmen, and families rushed to the spot. By 1863 more than three thousand residents lived there.

The remote location of the thriving town made it difficult for explorers to readily find. Signs posted along the trail into Bannack that read "Kepe to the trale next to the bluffe" and "Tu Grass Hopper Diggings 30 Myles" helped guide people to the destination.

Lucia's time in Montana was supposed to be brief, but her uncle decided they should stay on and help make Bannack the first territorial capital. Her time in the region turned out to be indefinite after the chief justice was named governor.

"Bannack was tumultuous and rough, it was the headquarters of a band of highwaymen. Lawlessness and misrule seemed to be the prevailing spirit of the place. She was referring to a group of desperados led by Sheriff Henry Plummer. Plummer and his deputies pretended to arrest robbers and thieves terrorizing the area, but were actually leading the bandits who perpetrated the crimes. He was eventually found out, captured and hanged from his own gallows."

In the midst of the civil unrest were law-abiding homesteaders and parents who were anxious to have their children in school. Lucia was asked to take charge of locating a schoolhouse and acting as the town's first teacher. Equipping the classroom with the tools needed to start class was difficult. Makeshift chairs and desks had to be acquired as well as books on a variety of subjects.

When the first term began in mid-1864, children met at the Edgerton home for morning sessions. By the fall semester, students were meeting at a cabin that had been built specifically for use as a school.

"I cannot remember the name of all the scholars in that school. I very much regret to say that, and I know where only a few of them are living, at the opening of the twentieth century... A few pupils of mine are scattered in other lands. I trust that all of them are living, and remember affectionately our Bannack University of humble pretensions, but which sought to fulfill its mission and which, so far as I know, was the first school taught within what is now the state of Montana."

In 1868 Lucia left Montana to teach school in the southern states to children who had been denied the chance to learn. She was part of the Freedmen's Bureau, an organization founded in 1865 to help black communities establish schools and churches. In addition to teaching, Lucia wrote stories about her experience as an educator and had several of those articles published in magazines.

No matter where the work took her, she recalled the time spent teaching in Montana as one of the most rewarding adventures she ever embarked on.

"Since that remote time in Montana, I have been identified for a period with one of the historic schools of the country of some repute, usefulness, and promise, but I look back to the days I spent striving to help the little children in Bannack with a profound gratification. The school was not pretentious, but it was in response to the yearning for education, and it was the first."

Leave a Comment Here